(Press-News.org) Have you ever been cut off in traffic by another driver, leaving you still seething miles later? Or been interrupted by a colleague in a meeting, and found yourself replaying the event in your head even after you've left work for the day? Minor rude events like this happen frequently, and you may be surprised by the magnitude of the effects they have on our decision-making and functioning. In fact, recent research co-authored by management professor Trevor Foulk at the University of Maryland's Robert H. Smith School of Business suggests that in certain situations, incidental rudeness like this can be deadly.

In "Trapped by A First Hypothesis: How Rudeness Leads to Anchoring" forthcoming in the Journal of Applied Psychology, Foulk and co-authors Binyamin Cooper of Carnegie Mellon University, Christopher R. Giordano and Amir Erez of the University of Florida, Heather Reed of Envision Physician Services, and Kent B. Berg of Thomas Jefferson University Hospital looked at how experiencing rudeness amplifies the "anchoring bias." The anchoring bias is the tendency to get fixated on one piece of information when making a decision (even if that piece of information is irrelevant).

For example, if someone asks, "Do you think the Mississippi River is shorter or longer than 500 miles?," that suggestion of 500 miles can become an anchor that can influence how long you think the Mississippi River is. When it happens, it's difficult to stray very far from that initial suggestion, says Foulk.

The anchoring bias can happen in a lot of different situations, but it's very common in medical diagnoses and negotiations. "If you go into the doctor and say 'I think I'm having a heart attack,' that can become an anchor and the doctor may get fixated on that diagnosis, even if you're just having indigestion," Foulk explains. "If doctors don't move off anchors enough, they'll start treating the wrong thing."

Because anchoring can happen in many scenarios, Foulk and his co-authors wanted to study more about the phenomenon and what factors exacerbate or mitigate it. They have been studying rudeness in the workplace for years and knew from previous studies that when people experience rudeness, it takes up a lot of their psychological resources and narrows their mindset. They suspected this might play a role in the anchoring effect.

To test their theory, the researchers ran a medical simulation with anesthesiology residents. The residents had to diagnose and treat the patient, and right before the simulation started, the participants were given an (incorrect) suggestion about the patient's condition. This suggestion served as the anchor, but then throughout the exercise, the simulator provided feedback that the ailment was not the suggested diagnosis, but instead something else.

In some iterations, before the simulation started, the researchers had one doctor enter the room and act rudely toward another doctor in front of the residents.

"What we find is that when they experienced rudeness prior to the simulation starting, they kept on treating the wrong thing, even in the presence of consistent information that it was actually something else," says Foulk. "They kept treating the anchor, even though they had plenty of reason to understand that the anchor diagnosis was not what the patient was suffering from."

This effect was replicated across a variety of other tasks, including negotiations as well as general knowledge tasks. Across the different studies, the results were consistent - experiencing rudeness makes it more likely that a person will get anchored to the first suggestion they hear.

"Across the four studies, we find that both witnessed and directly-experienced rudeness seemed to have a similar effect," says Foulk. "Basically, what we're observing is a narrowing effect. Rudeness narrows your perspective, and that narrowed perspective makes anchoring more likely."

In general, the anchoring tendency is usually not a big deal, says Foulk. "But when you're in these important, critical decision-making domains - like medical diagnoses or big negotiations - interpersonal interactions really matter a lot. Minor things can stay on top of us in a way that we don't realize."

To provide additional insights into this phenomenon, the researchers also explored ways to counteract it. Rudeness makes you more likely to anchor because it narrows your perspective, so the researchers explored two tasks that have been shown to expand your perspective - perspective-taking and information elaboration.

Perspective-taking helps you expand your perspective by seeing the world from another person's point of view, and information elaboration helps you see the situation from a wider perspective by thinking about it more broadly. Across their studies, the researchers found that both behaviors could counteract the effect of rudeness on anchoring.

While these interventions can help make rudeness less likely to anchor people, Foulk says these should be a last resort. The best remedy for the rudeness problem?

"In important domains, where people are making critical decisions, we really need to rethink the way we treat people," he says. "We never really did allow aggressive behavior at work. But we're fine with rudeness, and now we're learning more and more that small insults are equally impactful on people's performance."

And it needs to stop, he says.

"We tend to underestimate the performance implications of interpersonal treatment. We hear 'If you can't stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.' It's almost like being able to tolerate people's treatment of you is like a badge of honor. But the reality is that this bad treatment is having really deleterious effects on performance in domains that we care about - like medicine. It matters."

This is the fourth paper in a string of Foulk's research showing that rudeness negatively impacts medical performance, where the impacts can be much bigger - and much more dire - than the insults, he says.

"In simulations, we're finding that mortality is increased by rudeness. People could be dying because somebody insulted the surgeon before they started operating."

INFORMATION:

HOUSTON - (June 10, 2021) - Leaders who encourage their employees to learn on the job and speak up with ideas and suggestions for change have teams that are more effective and resilient in the face of unexpected situations, according to new research from Rice University and the University of Windsor.

"A Resource Model of Team Resilience Capacity and Learning" will appear in a special issue of Group & Organization Management. Authors Kyle Brykman, an assistant professor at the Odette School of Business at the University of Windsor, and Danielle King, an ...

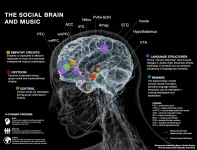

Music is a tool that has accompanied our evolutionary journey and provided a sense of comfort and social connection for millennia. New research published today in the American Psychologist provides a neuroscientific understanding of the social connection with a new map of the brain when playing music.

A team of social neuroscientists from Bar-Ilan University and the University of Chicago introduced a model of the brain that sheds light on the social functions and brain mechanisms that underlie the musical adaptations used for human connection. The model is unique because it focuses on what happens in the brain when people make music together, rather than when they listen to music individually.

The research was inspired by creative efforts of people around the world to reproduce ...

Chestnut Hill, Mass. (6/10/2021) - A British man who rejected the standard of care to treat his brain cancer has lived with the typically fatal glioblastoma tumor growing very slowly after adopting a ketogenic diet, providing a case study that researchers say reflects the benefits of using the body's own metabolism to fight this particularly aggressive cancer instead of chemo and radiation therapy.

Published recently in the journal Frontiers in Nutrition, the report is the first evaluation of the use of ketogenic metabolic therapy (KMT) without chemo or radiation interventions, on a patient diagnosed with IDH1-mutant glioblastoma (GBM). Ketogenic therapy is a non-toxic nutritional approach, viewed as complementary or ...

Just as the governor announced the start of python hunting season in Florida this month, researchers at the University of Central Florida have published a first- of-its-kind study that shows that near-infrared (NIR) spectrum cameras can help hunters more effectively track down these invasive snakes, especially at night.

The snakes, which can reach 26 feet in length and 200 pounds, have invaded the Everglades in Florida -- threatening native species and disrupting the ecosystem. The number of common native species observed in the Everglades since the snakes were first discovered in the 1990s dropped in some species by 90% through 2010, according ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Researchers from Cornell University's School of Applied and Engineering Physics and Samsung's Advanced Institute of Technology have created a first-of-its-kind metalens - a metamaterial lens - that can be focused using voltage instead of mechanically moving its components.

The proof of concept opens the door to a range of compact varifocal lenses for possible use in many imaging applications such as satellites, telescopes and microscopes, which traditionally focus light using curved lenses that adjust using mechanical parts. In some applications, moving traditional glass or plastic lenses ...

Climate change exerts great pressure for change on species and biodiversity. A recent study conducted by the University of Helsinki and the Finnish Environment Institute indicates that the few moth and butterfly species (Lepidoptera) capable of adjusting to a changing climate by advancing their flight period and moving further north have fared the best in Finland. In contrast, roughly 40% of Lepidoptera species have not been able to respond in either way, seeing their populations decline.

Climate change is bringing about rapid change in Finnish nature - can species keep up with the pace? Adjusting to climate change can manifest through earlier phenology such as moth and butterfly flight periods, bird nesting, or ...

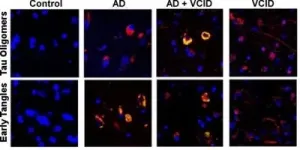

Researchers remain perplexed as to what causes dementia and how to treat and reverse the cognitive decline seen in patients. In a first-of-its-kind study, researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC), Harvard Medical School discovered that cis P-tau, a toxic, non-degradable version of a healthy brain protein, is an early marker of vascular dementia (VaD) and Alzheimer's disease (AD). Their results, published on June 2 in Science Translational Medicine, define the molecular mechanism that causes an accumulation of this toxic protein. Furthermore, they showed that ...

WACO, Texas (June 9, 2021) - Most people listen to music throughout their day and often near bedtime to wind down. But can that actually cause your sleep to suffer? When sleep researcher Michael Scullin, Ph.D., associate professor of psychology and neuroscience at Baylor University, realized he was waking in the middle of the night with a song stuck in his head, he saw an opportunity to study how music -- and particularly stuck songs -- might affect sleep patterns.

Scullin's recent study, published in Psychological Science, investigated the relationship between music listening and sleep, focusing on a rarely-explored mechanism: involuntary musical imagery, or "earworms," when a song or tune replays ...

June 10, 2021, CLEVELAND: A new Cleveland Clinic-led study has identified mechanisms by which COVID-19 can lead to Alzheimer's disease-like dementia. The findings, published in Alzheimer's Research & Therapy, indicate an overlap between COVID-19 and brain changes common in Alzheimer's, and may help inform risk management and therapeutic strategies for COVID-19-associated cognitive impairment.

Reports of neurological complications in COVID-19 patients and "long-hauler" patients whose symptoms persist after the infection clears are becoming more common, suggesting that SARS-CoV-2 (the virus that causes COVID-19) may have lasting effects on brain function. However, it is not yet well understood how the virus leads to neurological issues.

"While some studies suggest ...

The human heart contracts about 70 times per minute, while that of a rat contracts over 300 times; what accounts for this difference? In a new study publishing 10th June in the open-access journal PLOS Biology, led by Michael Geeves and Mark Wass of the University of Kent and Leslie Leinwand from the University of Colorado Boulder, reveal the molecular differences in the heart muscle protein beta myosin that underly the large difference in contraction velocity between the two species.

Myosin is a "molecular motor" - an intricate nanomachine that forms the dynamic core of a muscle's contractile machinery, burning ...