Fast heart, slow heart: Changes in the molecular motor myosin explain the difference

A molecular explanation for an old physiologic observation

2021-06-10

(Press-News.org) The human heart contracts about 70 times per minute, while that of a rat contracts over 300 times; what accounts for this difference? In a new study publishing 10th June in the open-access journal PLOS Biology, led by Michael Geeves and Mark Wass of the University of Kent and Leslie Leinwand from the University of Colorado Boulder, reveal the molecular differences in the heart muscle protein beta myosin that underly the large difference in contraction velocity between the two species.

Myosin is a "molecular motor" - an intricate nanomachine that forms the dynamic core of a muscle's contractile machinery, burning cellular chemical energy in the form of ATP to rapidly and reversibly exert force against cables of actin. In so doing, it pulls the ends of the muscle cell closer together, causing muscle contraction. It has long been known that the maximal rate of contraction, called V0, varies predictably among mammals: In small mammals with their high metabolic rate, V0 is higher than in larger mammals, which have lower metabolic rates.

There are multiple kinds of myosin, which serve diverse roles not only in muscle but in every other cell of the body. It is the muscle-specific forms, called sarcomeric myosins, that shows the pronounced difference in V0 between species (the V0 values of non-muscle isoforms show little in the way of between-species differences). Not surprisingly, the amino acid sequence of these sarcomeric myosins varies between species, but which of these variations is responsible for the small mammal/big mammal difference in V0?

The authors compared beta myosin (the sarcomeric myosin present in slow muscle and in heart) sequences from 67 different mammals, and found that differences in the motor domain, the region of the molecule that binds and burns ATP, were most closely correlated with differences in V0. Further analysis of two different evolutionary lineages of mammals, each containing both large and small species, led them to identify 16 sites on the molecule that were associated specifically with size difference, independent of lineage. Humans and rats differed at nine of these sites. When the authors then changed the human protein to include the rat amino acids at these sites, the rat-human chimeric protein functioned more like the rat protein, with a doubling of motility and a faster release of the waste product ADP (the velocity-limiting step in contraction).

An increase in size is a common trend in mammalian evolution, seen in multiple lineages, including our own. "The change in V0 that we observed in the chimeric protein demonstrates that changes in these residues likely enabled the slower heart rate required in larger animals as they have evolved from small to large," Chloe Johnson one of the authors said. "The fact that the two lineages tested in this study both hit upon the same solution to slowing contraction suggests there may be few molecular options for altering beta myosin's rate of contraction."

INFORMATION:

Research Article

Peer reviewed; Experimental Study; Cells

In your coverage please use these URLs to provide access to the freely available articles in PLOS Biology: http://journals.plos.org/plosbiology/article?id=10.1371/journal.pbio.3001248

Citation: Johnson CA, McGreig JE, Jeanfavre ST, Walklate J, Vera CD, Farré M, et al. (2021) Identification of sequence changes in myosin II that adjust muscle contraction velocity. PLoS Biol 19(6): e3001248. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pbio.3001248

Funding: MNW was supported by a Royal Society research grant. JEM was supported by an EPSRC PhD studentship. MAG & JW were supported by funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 777204 SILICO FCM. LAL was supported by NIH GM29090 and NIH HL117138. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing Interests: I have read the journal's policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: LAL owns stock in MyoKardia, Inc. and has a Sponsored Research Agreement with MyoKardia, Inc.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-10

Pairing sky-mapping algorithms with advanced immunofluorescence imaging of cancer biopsies, researchers at The Mark Foundation Center for Advanced Genomics and Imaging at Johns Hopkins University and the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy developed a robust platform to guide immunotherapy by predicting which cancers will respond to specific therapies targeting the immune system.

A new platform, called AstroPath, melds astronomic image analysis and mapping with pathology specimens to analyze microscopic images of tumors.

Immunofluorescent imaging, using antibodies with fluorescent tags, enables researchers to visualize multiple cellular proteins simultaneously and determine their pattern and strength of expression. Applying AstroPath, ...

2021-06-10

The team say their findings have implications for the treatment of viruses in future.

Researchers from the Universities of York and Leeds, collaborating with the Hilvert Laboratory at the ETH Zürich, studied the structure, assembly and evolution of a 'container' composed of a bacterial enzyme.

The study - published in the journal Science - details the structural transformation of these virus-like particles into larger protein 'containers'.

It also reveals that packaging of the genetic cargo in these containers becomes more efficient during the later stages of evolution. They show that this is because the genome inside evolves hallmarks of a mechanism widely ...

2021-06-10

The specific traits of a plant's roots determine the climatic conditions under which a particular plant prevails. A new study led by the University of Wyoming sheds light on this relationship -- and challenges the nature of ecological trade-offs.

Daniel Laughlin, an associate professor in the UW Department of Botany and director of the Global Vegetation Project, led the study, which included researchers from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research in Leipzig, Germany; Leipzig University; and Wageningen University & Research in Wageningen, Netherlands.

"We found that root traits can explain species distributions across the planet, which has never been attempted ...

2021-06-10

It's often cancer's spread, not the original tumor, that poses the disease's most deadly risk.

"And yet metastasis is one of the most poorly understood aspects of cancer biology," says Kamen Simeonov, an M.D.-Ph.D. student at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine.

In a new study, a team led by Simeonov and School of Veterinary Medicine professor Christopher Lengner has made strides toward deepening that understanding by tracking the development of metastatic cells. Their work used a mouse model of pancreatic cancer and cutting-edge techniques to trace the lineage and gene expression patterns of individual cancer cells. They found a spectrum of aggression in the cells that arose, with cells ...

2021-06-10

WOODS HOLE, Mass. -- Many animals have evolved camouflage tactics for self-defense, but some butterflies and moths have taken it even further: They've developed transparent wings, making them almost invisible to predators.

A team led by Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) scientists studied the development of one such species, the glasswing butterfly, Greta oto, to see through the secrets of this natural stealth technology. Their work was published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Although transparent structures in animals are well established, they appear far more often in ...

2021-06-10

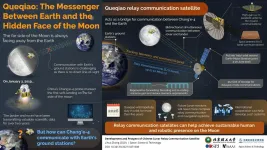

Because of a phenomenon called gravitational locking, the Moon always faces the Earth from the same side. This proved useful in the early lunar landing missions in the 20th century, as there was always a direct line of sight for uninterrupted radiocommunications between Earth ground stations and equipment on the Moon. However, gravitational locking makes exploring the hidden face of the moon--the far side--much more challenging, because signals cannot be sent directly across the Moon towards Earth.

Still, in January 2019, China's lunar probe Chang'e-4 marked the first time a spacecraft landed on the far side of the Moon. Both the lander and the lunar rover it carried have been gathering and sending back images and ...

2021-06-10

Philadelphia, June 10, 2021 - A new study from researchers at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and the University of Pennsylvania's Annenberg Public Policy Center found that 18- to 24-year-olds who use cell phones while driving are more likely to engage in other risky driving behaviors associated with "acting-without-thinking," a form of impulsivity. These findings suggest the importance of developing new strategies to prevent risky driving in young adults, especially those with impulsive personalities. The study was recently published in the International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health.

Cell phone use while driving has been linked to increased crash and near-crash risk. Despite bans on handheld cell phone use ...

2021-06-10

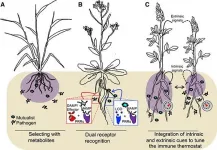

Plants are constantly exposed to microbes: pathogens that cause disease, commensals that cause no harm or benefit, and mutualists that promote plant growth or help fend off pathogens. For example, most land plants can form positive relationships with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to improve nutrient uptake. How plants fight off pathogens without also killing beneficial microbes or wasting energy on commensal microbes is a largely unanswered question.

In fact, when scientists within the field of Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions were asked to come up with their Top 10 Unanswered Questions, the #1 question was "How do plants engage with beneficial microorganisms while at the same time restricting ...

2021-06-10

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. -- Imagine being woken up at 3 a.m. to navigate a corn maze, memorize 20 items on a shopping list or pass your driver's test.

According to a new analysis out of West Virginia University, that's often what it's like to be a rodent in a biomedical study. Mice and rats, which make up the vast majority of animal models, are nocturnal. Yet a survey of animal studies across eight behavioral neuroscience domains showed that most behavioral testing is conducted during the day, when the rodents would normally be at rest.

"There are these dramatic daily fluctuations--in metabolism, in immune function, in learning and ...

2021-06-10

Philadelphia, June 10, 2021 - The collection of nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) samples for COVID-19 diagnostic testing poses challenges including exposure risk to healthcare workers and supply chain constraints. Saliva samples are easier to collect but can be mixed with mucus or blood, and some studies have found they produce less accurate results. A team of researchers has found that an innovative protocol that processes saliva samples with a bead mill homogenizer before real-time PCR (RT-PCR) testing results in higher sensitivity compared to NPS samples. Their protocol appears in The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics, published by Elsevier.

"Saliva as a sample type for COVID-19 testing ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Fast heart, slow heart: Changes in the molecular motor myosin explain the difference

A molecular explanation for an old physiologic observation