(Press-News.org) The specific traits of a plant's roots determine the climatic conditions under which a particular plant prevails. A new study led by the University of Wyoming sheds light on this relationship -- and challenges the nature of ecological trade-offs.

Daniel Laughlin, an associate professor in the UW Department of Botany and director of the Global Vegetation Project, led the study, which included researchers from the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research in Leipzig, Germany; Leipzig University; and Wageningen University & Research in Wageningen, Netherlands.

"We found that root traits can explain species distributions across the planet, which has never been attempted before at such a scale," Laughlin says. "We found that species with thick and dense roots were more likely to occur in warm climates, but species with thin and low density roots were more likely to occur in cold climates. This impacts their ability to acquire resources like nutrients and engage in symbiotic relationships with mycorrhizal fungi."

Laughlin is lead author of a paper, titled "Root Traits Explain Plant Species Distributions Along Climatic Gradients, Yet Challenge the Nature of Ecological Trade-Offs," that was published today (June 10) in Nature Ecology & Evolution. The online-only journal publishes, on a monthly basis, the best research from across ecology and evolutionary biology.

The paper includes contributors from more than 50 academic institutions, environmental agencies, institutes and laboratories.

Plant roots generally remain hidden below the ground, but their role for the distribution of plants should not be underestimated. Roots are essential for water and nutrient uptake, yet little is known about the influence of root traits on species distribution.

To investigate this relationship, an international team of researchers analyzed the root trait database, GRooT, and the vegetation database, known as sPlot. Each is the largest database of its kind. The work was facilitated by the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research's synthesis center, sDiv, which supports collaboration of scientists from different countries and disciplines.

Researchers analyzed several plant root traits. These included the specific root length and root diameter, as well as the root tissue density and root nitrogen content. These root traits were compared to the environmental conditions under which these plants occur. Researchers found that, in forests, species with relatively thick fine roots and high root tissue density were more likely to occur in warm climates, while species with more delicate and longer fine roots and low root tissue density were found more often in cold climates -- a classic trade-off.

By contrast, forest species with large-diameter roots and high root tissue density were more commonly associated with dry climates, but species with the opposite trait values were not associated with wet climates. Instead, a diversity of root traits occurred in warm or wet climates.

Laughlin says the findings are important because roots are literally foundational to plant survival, yet scientists have neglected roots for too long.

"Understanding how root traits are related to climate gradients, like water and temperature, will determine how species respond and shift their distributions in response to climate change," he says.

Study Challenges Ecological Trade-Offs

Ecological theory is built on trade-offs, where trait differences among species evolved as adaptations to different environments. This prevailing view of trade-offs in ecological theory may have hindered the discovery of unidirectional benefits that could be widespread in nature. At the species level, particularly, discerning the difference between trade-offs and unidirectional benefits would advance the understanding of how individual traits affect community assembly, according to the study.

But plants can't cover all of the bases. For plants, this means that low trait values -- such as low specific root length in this study -- are associated with advantages under certain climate conditions. On the flip side, high trait values -- such as high specific root length -- confer benefits under opposing conditions.

However, certain root traits did not follow this general ecological theory. Rather, the certain root traits were associated with unidirectional benefits. Translated, this means there is a benefit for high trait values in certain environmental conditions, but no benefit of low trait values in other conditions.

"We were surprised at how common these unidirectional benefits were in roots compared to classic trade-offs," Laughlin says.

A classic trade-off would be when one species, such as cottonwoods, is highly adapted to wet riparian soil, but it simply dies in the dry prairie because it is not adapted to dry conditions. In contrast, some of the dry prairie grasses thrive in the dry soil, but may die in the wet riparian soil or else be overtopped by more productive species along the river, Laughlin says. This classic idea has pervaded ecological thought.

"We found something more nuanced, where a small set of traits enhanced occurrence of species in harsh climates that are dry and cold, but a large set of traits and species could tolerate benign climates that are warm and wet," he explains. "In other words, traits can be beneficial at one end of the climate gradient and neutral at the other end."

"This challenges our understanding of how traits drive species distributions, which we have been puzzled by as a scientific community," adds Alexandra Weigelt, a plant ecologist at Leipzig University and a member of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research, and last senior author of the paper.

This suggests that unidirectional benefits may be more widespread than previously thought, the study concludes. Unidirectional benefits were consistently associated with the more extreme cold and dry climates that are more resource-limited than warm and wet climates. By contrast, warm and wet climates were associated with a larger diversity of root traits, according to the study.

Laughlin admits there is still a lack of broad-scale empirical evidence to fully challenge the trade-off ecological theory, at least at this time. But this study expands on previous hints about the influence of unidirectional benefits.

"We believe that our work helps to understand the trait combinations that are possible in certain climate zones. This is important knowledge for ecosystem restoration in a changing world," says Liesje Mommer, a plant ecologist at Wageningen University & Research.

INFORMATION:

The research was funded by the German Research Foundation.

It's often cancer's spread, not the original tumor, that poses the disease's most deadly risk.

"And yet metastasis is one of the most poorly understood aspects of cancer biology," says Kamen Simeonov, an M.D.-Ph.D. student at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine.

In a new study, a team led by Simeonov and School of Veterinary Medicine professor Christopher Lengner has made strides toward deepening that understanding by tracking the development of metastatic cells. Their work used a mouse model of pancreatic cancer and cutting-edge techniques to trace the lineage and gene expression patterns of individual cancer cells. They found a spectrum of aggression in the cells that arose, with cells ...

WOODS HOLE, Mass. -- Many animals have evolved camouflage tactics for self-defense, but some butterflies and moths have taken it even further: They've developed transparent wings, making them almost invisible to predators.

A team led by Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL) scientists studied the development of one such species, the glasswing butterfly, Greta oto, to see through the secrets of this natural stealth technology. Their work was published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

Although transparent structures in animals are well established, they appear far more often in ...

Because of a phenomenon called gravitational locking, the Moon always faces the Earth from the same side. This proved useful in the early lunar landing missions in the 20th century, as there was always a direct line of sight for uninterrupted radiocommunications between Earth ground stations and equipment on the Moon. However, gravitational locking makes exploring the hidden face of the moon--the far side--much more challenging, because signals cannot be sent directly across the Moon towards Earth.

Still, in January 2019, China's lunar probe Chang'e-4 marked the first time a spacecraft landed on the far side of the Moon. Both the lander and the lunar rover it carried have been gathering and sending back images and ...

Philadelphia, June 10, 2021 - A new study from researchers at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and the University of Pennsylvania's Annenberg Public Policy Center found that 18- to 24-year-olds who use cell phones while driving are more likely to engage in other risky driving behaviors associated with "acting-without-thinking," a form of impulsivity. These findings suggest the importance of developing new strategies to prevent risky driving in young adults, especially those with impulsive personalities. The study was recently published in the International Journal of Environmental Research Public Health.

Cell phone use while driving has been linked to increased crash and near-crash risk. Despite bans on handheld cell phone use ...

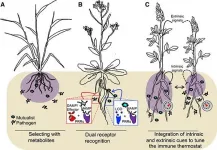

Plants are constantly exposed to microbes: pathogens that cause disease, commensals that cause no harm or benefit, and mutualists that promote plant growth or help fend off pathogens. For example, most land plants can form positive relationships with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi to improve nutrient uptake. How plants fight off pathogens without also killing beneficial microbes or wasting energy on commensal microbes is a largely unanswered question.

In fact, when scientists within the field of Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions were asked to come up with their Top 10 Unanswered Questions, the #1 question was "How do plants engage with beneficial microorganisms while at the same time restricting ...

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. -- Imagine being woken up at 3 a.m. to navigate a corn maze, memorize 20 items on a shopping list or pass your driver's test.

According to a new analysis out of West Virginia University, that's often what it's like to be a rodent in a biomedical study. Mice and rats, which make up the vast majority of animal models, are nocturnal. Yet a survey of animal studies across eight behavioral neuroscience domains showed that most behavioral testing is conducted during the day, when the rodents would normally be at rest.

"There are these dramatic daily fluctuations--in metabolism, in immune function, in learning and ...

Philadelphia, June 10, 2021 - The collection of nasopharyngeal swab (NPS) samples for COVID-19 diagnostic testing poses challenges including exposure risk to healthcare workers and supply chain constraints. Saliva samples are easier to collect but can be mixed with mucus or blood, and some studies have found they produce less accurate results. A team of researchers has found that an innovative protocol that processes saliva samples with a bead mill homogenizer before real-time PCR (RT-PCR) testing results in higher sensitivity compared to NPS samples. Their protocol appears in The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics, published by Elsevier.

"Saliva as a sample type for COVID-19 testing ...

WASHINGTON, June 10, 2021 -- The demand for flexible wearable electronics has spiked with the dramatic growth of smart devices that can exchange data with other devices over the internet with embedded sensors, software, and other technologies. Researchers consequently have focused on exploring flexible energy storage devices, such as flexible supercapacitators (FSCs), that are lightweight and safe and easily integrate with other devices. FSCs have high power density and fast charge and discharge rates.

Printing electronics, manufacturing electronics devices and systems by using conventional printing techniques, has proved to be an economical, simple, and scalable strategy for fabricating FSCs. Traditional micromanufacturing ...

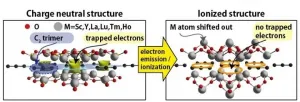

An exploratory investigation into the behavior of materials with desirable electric properties resulted in the discovery of a structural phase of two-dimensional (2D) materials. The new family of materials are electrides, wherein electrons occupy a space usually reserved for atoms or ions instead of orbiting the nucleus of an atom or ion. The stable, low-energy, tunable materials could have potential applications in nanotechnologies.

The international research team, led by Hannes Raebiger, associate professor in the Department of Physics at Yokohama National University in Japan, published their results on June 10th as frontispiece in Advanced Functional Materials.

Initially, the team ...

Researchers from Skoltech have designed and conducted experiments measuring gas permeability under various conditions for ice-containing sediments mimicking permafrost. Their results can be useful both in modeling and testing techniques for gas production from Arctic reservoirs and in tracing methane emission in high latitudes. The paper was published in the journal Energy&Fuels.

Permafrost, even though it sounds very stable and permanent, is actually quite diverse: depending on the composition of the frozen ground, pressure, temperature and so on, it can have varying properties, which are extremely important if you want to build something on permafrost, ...