(Press-News.org) Getting energy and nutrients from the environment - that is, eating - is such an important function that it has been regulated through sophisticated mechanisms over hundreds of millions of years. Some of these mechanisms are only now beginning to be unravelled. A group at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) has found one of their key components - a switch that controls the ability of organisms to adapt to low cellular nutrient levels.

The protein involved is RagA, which is part of the mTOR molecular pathway, whose importance in metabolic activity regulation has been known for decades now. CNIO researchers have found that if RagA is continuously activated, cells do not know that there are no sufficient nutrients and so keep on using energy as if nutrients were plentiful.

The study is published in Nature Communications this week. The corresponding author is Alejo Efeyan, Leader of the Metabolism and Cell Signalling Group at the CNIO, while Celia de la Calle is the first author.

"Today, nutrients are always abundant" Efeyan says, "but the conditions under which we evolved were very different." "Our organism adapts to feeding-fasting cycles, and our cells are prepared to respond to them. We have discovered that RagA activation is key to our adaptation to fasting conditions".

The importance of the RagA molecular pathway is on a par with that of other components that play a key role in nutrition, like insulin. However, RagA was identified not that long ago, and comparably little is known about its role in the regulation of metabolism. Understanding how the Rag proteins operate in the cell could enable us to find new strategies to fight obesity and obesity-related diseases, like fatty liver or cancer.

"Adapting to fluctuations in nutrient levels is fundamental in all living organisms," Efeyan explains. "This is an ancient molecular pathway, older than insulin actually. It is found even in yeasts. Despite this, little is known about how it affects normal physiology and how its activity is deregulated in obesity and obesity-related conditions."

'Saving mode' on

In healthy organisms, RagA detects low nutrient levels and switches off accordingly, with cell metabolism enabling an "energy-saving mode". The organism then becomes more "frugal", using the resources stored when nutrients were abundant.

When RagA is activated, mice "continue using energy; they do not adjust their metabolism to normal feeding-fasting cycles. Their cells 'believe' nutrients are abundant all the time and do not save energy," says Celia de la Calle, first author of the study.

The researchers of the Metabolism and Cell Signalling Group at CNIO had previously shown the importance of this system. Using mice embryos with permanent activation of RagA, they showed that the animals could not adapt to nutrient deficit at birth, when nutrients are no longer delivered through the placenta.

The importance of sensing fasting

In the study, the researchers prevented RagA from switching off only partially, so that the mice could survive. However, they had metabolic alterations that spanned glucose, amino acid, ketone and lipid homeostasis, among others.

The mice in the study lived around nine months, less than normal animals. The authors of the study believe this is why they could not detect signs of accelerated aging. They expected they would, since fasting and low-calorie intake increase lifespan in some species, and the mechanisms involved are associated with mTOR, the molecular pathway in which RagA participates.

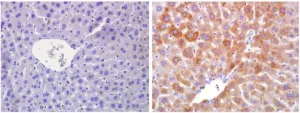

In addition, the authors of the study generated adult mice with RagA activation in the liver only. Numerous effects were observed in this organ, which plays a key role in energy metabolism.

Simulating fasting benefits?

Identifying RagA as a switch in the "energy-saving mode" is the starting point of new research lines. So far, researchers have studied what happens when RagA is permanently activated: animals are never in a fasted state, and the long-term consequences are serious. But what would happen if RagA were permanently inhibited?

"We want to explore this path," Efeyan says. "With partial pharmacological inhibition of this metabolic pathway, we might get the metabolic benefits of fasting without the difficulties of limited food intake."

INFORMATION:

This study was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, the Carlos III Health Institute, the European Research Council, the European Development Fund, the Spanish Association against Cancer, the Fero Foundation, and the EMBO Young Investigator Programme.

The encryption algorithm GEA-1 was implemented in mobile phones in the 1990s to encrypt data connections. Since then, it has been kept secret. Now, a research team from Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB), together with colleagues from France and Norway, has analysed the algorithm and has come to the following conclusion: GEA-1 is so easy to break that it must be a deliberately weak encryption that was built in as a backdoor. Although the vulnerability is still present in many modern mobile phones, it no longer poses any significant threat to users, according to the researchers.

Backdoors not useful according to researchers

"Even though intelligence services and ministers of the interior understandably want such backdoors ...

ENVIRONMENT Diesel-polluted soil from now defunct military outposts in Greenland can be remediated using naturally occurring soil bacteria according to an extensive five-year experiment in Mestersvig, East Greenland, to which the University of Copenhagen has contributed.

Mothballed military outposts and stacks of rusting oil drums aren't an unusual sight in Greenland. Indeed, there are about 30 abandoned military installations in Greenland where diesel, once used to keep generators and other machinery running, may have seeped into the ground.

This is the case with Station 9117 Mestersvig, an abandoned military airfield ...

These findings were published in the journal Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences on 8 June 2021.

Huge splicing diversity in the brain

The human genome was sequenced around 20 years ago. Since then, the sequence information encoding our proteins is known - at least in principle. However, this information is not continuously stored in the individual genes, but is divided into smaller coding sections. These coding sections, also known as exons, are assembled in a process called splicing. Depending on the gene, different exon combinations are possible, which is why they are referred to as different or ...

With increasing vaccination rates and decreasing numbers of infections, the population's feeling of safety is also rising. As the results of the 37th edition of the BfR-Corona-Monitor, a regular survey conducted by the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR), show, the majority of the population in Germany thinks it can control its risk of an infection well. "62 percent are confident that they can protect themselves from an infection with the coronavirus," says BfR-President Professor Dr. Dr. Andreas Hensel. "We see that the feeling of safety has increased considerably. ...

Chinese researchers have recently discovered links between reduction in microbial stability and soil carbon loss in the active layer of degraded alpine permafrost on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau (QTP).

The researchers, headed by Prof. CHEN Shengyun from the Northwest Institute of Eco-Environment and Resources (NIEER) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), and XUE Kai from University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, conducted a combined in-depth analysis of soil microbial communities and their co-occurrence networks in the active permafrost layer along an extensive gradient of permafrost degradation.

The QTP encompasses the largest extent of high-altitude mountain ...

Greater Helsinki -- Transitioning to low-carbon energy production is the biggest climate challenge to overcome. Many countries are already looking to adopt clean heating solutions more widely, with the International Energy Agency projecting that by 2045 nearly half of global heating will be done with heat pumps. To ensure speedy uptake, governments are likely to offer subsidies to ensure these energy-efficient options actually make their way into homes and offices.

A new study from Aalto University assesses the impact of heat pumps on energy consumption as well as how ...

Research published in the journal ACS Materials and Interfaces has provided new understanding of how false-negative results in Lateral Flow Tests occur and provides opportunity for simple improvements to be made.

Lateral Flow Devices were introduced late in 2020 on a global scale to help detect novel coronavirus infection in individuals, with test results produced rapidly in half an hour or less. However, their potential has been somewhat hindered by inadequate sensitivity, with a high number of false-negative results.

Using X-ray fluorescence imaging from Diamond Light Source, researchers from King's College London ...

Researchers from the University of Kent's School of Psychology have found that when people are presented with the idea of a Covid-19 "immunity passport", they show less willingness to follow social distancing and face covering guidelines. However, this willingness seems to return when people read more cautious information about Covid-19 immunity.

PhD students Ricky Green and Mikey Biddlestone and Professor Karen Douglas asked participants from the UK and USA to imagine they had either recovered from Covid-19 or were currently infected. Participants asked to imagine ...

Several different causes of ageing have been discovered, but the question remains whether there are common underlying mechanisms that determine ageing and lifespan. Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Biology of Ageing and the CECAD Cluster of Excellence in Ageing research at the University Cologne have now come across folate metabolism in their search for such basic mechanisms. Its regulation underlies many known ageing signalling pathways and leads to longevity. This may provide a new possibility to broadly improve human health during ageing.

In recent decades, ...

In an international study published by the journal Environment International, the University of Surrey led an international team of air pollution experts in monitoring pollution hotspots in 10 global cities: Dhaka (Bangladesh); São Paulo (Brazil); Guangzhou (China); Medellín (Colombia); Cairo (Egypt); Addis Ababa (Ethiopia); Chennai (India); Sulaymaniyah (Iraq); Blantyre (Malawi); and Dar-es-Salaam (Tanzania).

Surrey's Global Centre for Clean Air Research (GCARE) set out to investigate whether the amount of fine air pollution particles (PM2.5) drivers inhaled is connected to the duration drivers spend in pollution hotspots and socio-economic indicators such ...