(Press-News.org) It sounds like a plot from a Quentin Tarantino movie -- something sets off natural killers and sends them on a killing spree.

But instead of characters in a movie, these natural killers are part of the human immune system and their targets are breast cancer tumor cells. The triggers are fusion proteins developed by Clemson University researchers that link the two together.

"The idea is to use this bifunctional protein to bridge the natural killer cells and breast cancer tumor cells," said Yanzhang (Charlie) Wei, a professor in the College of Science's Department of Biological Sciences. "If the two cells are brought close enough together through this receptor ligand connection, the natural killer cells can release what I call killing machinery to have the tumor cells killed."

It's a novel approach to developing breast cancer-specific immunotherapy and could lead to new treatment options for the world's most common cancer.

About one in eight women in the U.S. and one in 1,000 men will develop invasive breast cancer during their lives. Breast cancer is the second leading cause of cancer death in women in the U.S., trailing only lung cancer. The American Cancer Society estimates that about 43,600 U.S. women will die from the disease this year.

Immunotherapy harnesses the power of the body's immune system to kill cancer cells.

"Very simply, cancer is uncontrolled cell growth. Some cells will become abnormal and have the potential to become cancer," Wei said. "The immune system can recognize these abnormal cells and destroy them before they become cancer cells. Unfortunately for those who develop cancer, the immune system is not working very well because of gene mutations and environmental factors. The result is that the cancer cells won the fight between the immune system and the tumors."

Most breast cancer targeting therapies target one of three receptors: estrogen receptors, progesterone receptors or epidermal growth factor receptors. However, up to 20 percent of breast cancers do not express these receptors. These cancers are known as triple-negative breast cancer. Triple-negative is the most lethal subtype of breast cancer because of high heterogeneity, high metastasis frequency, early relapse after standard chemotherapy and lack of efficient treatment options.

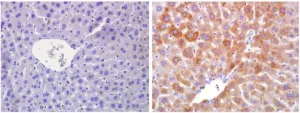

In this novel research, Wei and his researchers targeted prolactin receptors. Prolactin is a natural hormone in the body and plays a role in breast growth and milk production during breastfeeding. Breast cancer cells overexpress prolactin receptors.

"When people are diagnosed with breast cancer, and it's called triple-negative, it is not good news," Wei said. "This has the potential to give patients another option."

Over 90 percent of breast cancer cells express prolactin receptors, including triple-negative breast cancer cells.

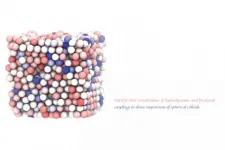

Wei and his team developed a bifunctional protein. One part is a mutated form of prolactin that can still bind to the prolactin receptor but blocks signal transduction that would promote tumor growth. The other part is an extracellular domain of major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related protein (MICA).

When the MICA binds to the prolactin receptor, it activates the natural killer cells.

"One of the things tumor cells do is to inhibit natural killer cell activation, so we use these artificial bifunctional proteins to connect natural killer cells and activate them to enhance the killing of the breast cancer cells without increased cytotoxicity," Wei said.

Wei is now seeking funding for an animal model study to confirm the results.

One big question is whether the bifunctional protein will bring natural killer cells to healthy cells in the body that also express prolactin receptors and kill them, too, causing severe side effects.

If the animal model studies are successful, the potential new treatment could move to human clinical trials.

"If we had the funding now and everything is what we expected in the animal model study, we could be in clinical trials in five or six years," he said. Wei said he expects the conversion from in-vitro and animal studies to clinical trials to be easier for this potential immunotherapy than others in the past because the protein created by the Clemson researchers uses human natural killer cells and breast cancer cells.

Developing new immunotherapy for cancer is nothing new to Wei. His research combining tumor cells with dendritic cells, an important part of the body's adaptive immune system, led to a dendritoma vaccine that proved effective in melanoma, renal cell carcinoma and neuroblastoma patients. The vaccine was patented and licensed to three biotech companies. Two companies are still pursuing the vaccine therapy or related therapy.

"It is my dream that someday we can create a group of these bifunctional proteins that could be used for other cancers by shifting the target molecule. We'd have the one part of the bifunctional protein that targets natural killer cells. The other part would target other cancer types that have unique markers," Wei said.

INFORMATION:

PLOS One, a peer-reviewed scientific journal published by the Public Library of Science, recently published Wei's breast cancer and natural killer cell study. It is titled "MICA-G129R: A bifunctional fusion protein increases PRLR-positive breast cancer cell death in co-culture with natural killer cells."

Clemson doctoral graduate Hui Ding is the paper's lead author. Other authors include Clemson doctoral student Garrett Buzzard; Clemson research assistant Sisi Huang; Michael Sehorn, associate professor in Clemson's Department of Genetics and Biochemistry; and Ken Marcus, a Clemson chemistry professor.

The research was partially supported by a Clemson Support for Early Exploration and Development (SEED) grant (CU SEED2017).

The College of Science pursues excellence in scientific discovery, learning and engagement that is both locally relevant and globally impactful. The life, physical and mathematical sciences converge to tackle some of tomorrow's scientific challenges, and our faculty are preparing the next generation of leading scientists. The College of Science offers high-impact transformational experiences such as research, internships and study abroad to help prepare our graduates for top industries, graduate programs and health professions. END

A group of researchers from the University of Jyvaskyla and Stanford University were part of an expedition to French Guiana to study tropical frogs in the Amazon. Various amphibian species of this region use ephemeral pools of water as their nurseries, and display unique preferences for specific physical and chemical characteristics. Despite species-specific preferences, researchers were surprised to find tadpoles of the dyeing poison frog surviving in an incredible range of both chemical (pH 3-8) and vertical (0-20 m in height) deposition sites. This research was published in the journal Ecology and Evolution in June 2021.

Neotropical frogs are special because, unlike species in temperate regions, many tropical frogs ...

Postdoctoral Researcher Outi Keinänen from the University of Helsinki developed a method to radiolabel plastic particles in order to observe their biodistribution on the basis of radioactivity with the help of positron emission tomography (PET). As a radiochemist, Keinänen has in her previous radiopharmaceutical studies utilised PET imaging combined with computed tomography (CT), which produces a very accurate image of the anatomical location of the radioactivity signal.

In the recently completed study, radiolabelled plastic particles were fed to mice, and their elimination from the body was followed with PET-CT scans. This was the first time that ...

Research published today in the Journal of General Virology has identified missed cases of SARS-CoV-2 by retrospective testing of throat swabs.

Researchers at the University of Nottingham screened 1,660 routine diagnostic specimens which had been collected at a Nottingham hospital between 2 January and 11 March 2020 and tested for SARS-CoV-2 by PCR. At this stage of the pandemic, there was very little COVID-19 testing available in hospitals, and to qualify patients had to meet a strict criterion, including recent travel to certain countries in Asia or contact with a known positive case.

Three previously unidentified cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection were identified by the retrospective screening, including one from a 75-year-old ...

The phenomenon of quantum nonlocality defies our everyday intuition. It shows the strong correlations between several quantum particles some of which change their state instantaneously when the others are measured, regardless of the distance between them. While this phenomenon has been confirmed for slow moving particles, it has been debated whether nonlocality is preserved when particles move very fast at velocities close to the speed of light, and even more so when those velocities are quantum mechanically indefinite. Now, researchers from the University of Vienna, the Austrian Academy of Sciences and the Perimeter Institute report in the latest issue of Physical Review Letters that ...

Tokyo, Japan - Colloids--mixtures of particles made from one substance, dispersed in another substance--crop up in numerous areas of everyday life, including cosmetics, food and dyes, and form important systems within our bodies. Understanding the behavior of colloids therefore has wide-ranging implications, yet investigating the rotation of spherical particles has been challenging. Now, an international team including researchers from The University of Tokyo Institute of Industrial Science has created particles with an off-center core or "eye" that can be tracked ...

Getting energy and nutrients from the environment - that is, eating - is such an important function that it has been regulated through sophisticated mechanisms over hundreds of millions of years. Some of these mechanisms are only now beginning to be unravelled. A group at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) has found one of their key components - a switch that controls the ability of organisms to adapt to low cellular nutrient levels.

The protein involved is RagA, which is part of the mTOR molecular pathway, whose importance in metabolic activity regulation has been known for decades now. CNIO researchers have found that if RagA is continuously activated, cells do not know that there are no sufficient nutrients and so ...

The encryption algorithm GEA-1 was implemented in mobile phones in the 1990s to encrypt data connections. Since then, it has been kept secret. Now, a research team from Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB), together with colleagues from France and Norway, has analysed the algorithm and has come to the following conclusion: GEA-1 is so easy to break that it must be a deliberately weak encryption that was built in as a backdoor. Although the vulnerability is still present in many modern mobile phones, it no longer poses any significant threat to users, according to the researchers.

Backdoors not useful according to researchers

"Even though intelligence services and ministers of the interior understandably want such backdoors ...

ENVIRONMENT Diesel-polluted soil from now defunct military outposts in Greenland can be remediated using naturally occurring soil bacteria according to an extensive five-year experiment in Mestersvig, East Greenland, to which the University of Copenhagen has contributed.

Mothballed military outposts and stacks of rusting oil drums aren't an unusual sight in Greenland. Indeed, there are about 30 abandoned military installations in Greenland where diesel, once used to keep generators and other machinery running, may have seeped into the ground.

This is the case with Station 9117 Mestersvig, an abandoned military airfield ...

These findings were published in the journal Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences on 8 June 2021.

Huge splicing diversity in the brain

The human genome was sequenced around 20 years ago. Since then, the sequence information encoding our proteins is known - at least in principle. However, this information is not continuously stored in the individual genes, but is divided into smaller coding sections. These coding sections, also known as exons, are assembled in a process called splicing. Depending on the gene, different exon combinations are possible, which is why they are referred to as different or ...

With increasing vaccination rates and decreasing numbers of infections, the population's feeling of safety is also rising. As the results of the 37th edition of the BfR-Corona-Monitor, a regular survey conducted by the German Federal Institute for Risk Assessment (BfR), show, the majority of the population in Germany thinks it can control its risk of an infection well. "62 percent are confident that they can protect themselves from an infection with the coronavirus," says BfR-President Professor Dr. Dr. Andreas Hensel. "We see that the feeling of safety has increased considerably. ...