(Press-News.org) EMBARGOED UNTIL 11 A.M. ET WEDNESDAY, JUNE 16, 2021

MADISON, Wis. -- Quantum computers could outperform classical computers at many tasks, but only if the errors that are an inevitable part of computational tasks are isolated rather than widespread events. Now, researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison have found evidence that errors are correlated across an entire superconducting quantum computing chip -- highlighting a problem that must be acknowledged and addressed in the quest for fault-tolerant quantum computers.

The researchers report their findings in a study published June 16 in the journal Nature, Importantly, their work also points to mitigation strategies.

"I think people have been approaching the problem of error correction in an overly optimistic way, blindly making the assumption that errors are not correlated," says UW-Madison physics Professor Robert McDermott, senior author of the study. "Our experiments show absolutely that errors are correlated, but as we identify problems and develop a deep physical understanding, we're going to find ways to work around them."

The bits in a classical computer can either be a 1 or a 0, but the qubits in a quantum computer can be 1, 0, or an arbitrary mixture -- a superposition -- of 1 and 0. Classical bits, then, can only make bit flip errors, such as when a 1 flips to 0. Qubits, however, can make two types of error: bit flips or phase flips, where a quantum superposition state changes.

To fix errors, computers must monitor them as they happen. But the laws of quantum physics say that only one error type can be monitored at a time in a single qubit, so a clever error correction protocol called the surface code has been proposed. The surface code involves a large array of connected qubits -- some do the computational work, while others are monitored to infer errors in the computational qubits. However, the surface code protocol works reliably only if events that cause errors are isolated, affecting at most a few qubits.

In earlier experiments, McDermott's group had seen hints that something was causing multiple qubits to flip at the same time. In this new study, they directly asked: are these flips independent, or are they correlated?

The research team designed a chip with four qubits made of the superconducting elements niobium and aluminum. The scientists cool the chip to nearly absolute zero, which makes it superconduct and protects it from error-causing interference from the outside environment.

To assess whether qubit flips were correlated, the researchers measured fluctuations in offset charge for all four qubits. The fluctuating offset charge is effectively a change in electric field at the qubit.

The team observed long periods of relative stability followed by sudden jumps in offset charge. The closer two qubits were together, the more likely they were to jump at the same time. These sudden changes were most likely caused by cosmic rays or background radiation in the lab, which both release charged particles. When one of these particles hits the chip, it frees up charges that affect nearby qubits.

This local effect can be easily mitigated with simple design changes. The bigger concern is what could happen next.

"If our model about particle impacts is correct, then we would expect that most of the energy is converted into vibrations in the chip that propagate over long distances," says Chris Wilen, a graduate student and lead author of the study. "As the energy spreads, the disturbance would lead to qubit flips that are correlated across the entire chip."

In their next set of experiments, that effect is exactly what they saw. They measured charge jumps in one qubit, as in the earlier experiments, then used the timing of these jumps to align measurements of the quantum states of two other qubits. Those two qubits should always be in the computational 1 state. Yet the researchers found that any time they saw a charge jump in the first qubit, the other two -- no matter how far away on the chip -- quickly flipped from the computational 1 state to the 0 state.

"It's a long-range effect, and it's really damaging," Wilen says. "It's destroying the quantum information stored in qubits."

Though this work could be viewed as a setback in the development of superconducting quantum computers, the researchers believe that their results will guide new research toward this problem. Groups at UW-Madison are already working on mitigation strategies.

"As we get closer to the ultimate goal of a fault-tolerant quantum computer, we're going to identify one new problem after another," McDermott says. "This is just part of the process of learning more about the system, providing a path to implementation of more resilient designs."

INFORMATION:

This study was done in collaboration with Fermilab, Stanford University, INFN Sezione di Roma, Google, Inc., and Lawrence Livermore National Lab. At UW-Madison, support was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy (#DE-SC0020313).

--Sarah Perdue, saperdue@wisc.edu, (608) 262-3051

CONTACT:

Robert McDermott, rfmcdermott@wisc.edu

DOWNLOAD IMAGES:

https://uwmadison.box.com/v/quantum-errors

Correlated errors in quantum computers emphasize need for design changes

It is possible to re-create a bird's song by reading only its brain activity, shows a first proof-of-concept study from the University of California San Diego. The researchers were able to reproduce the songbird's complex vocalizations down to the pitch, volume and timbre of the original.

Published June 16 in Current Biology, the study lays the foundation for building vocal prostheses for individuals who have lost the ability to speak.

"The current state of the art in communication prosthetics is implantable devices that allow you to generate textual output, writing up to 20 words per minute," said senior author Timothy Gentner, a professor of psychology and neurobiology ...

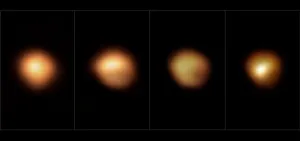

When Betelgeuse, a bright orange star in the constellation of Orion, became visibly darker in late 2019 and early 2020, the astronomy community was puzzled. A team of astronomers have now published new images of the star's surface, taken using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (ESO's VLT), that clearly show how its brightness changed. The new research reveals that the star was partially concealed by a cloud of dust, a discovery that solves the mystery of the "Great Dimming" of Betelgeuse.

Betelgeuse's dip in brightness -- a change noticeable even to the ...

What The Study Did: Researchers examined to what extent cannabis use is associated with thickness in brain areas measured by magnetic resonance imaging in a study of adolescents.

Authors: Matthew D. Albaugh, Ph.D., of the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine in Burlington, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2021.1258)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The ...

What The Study Did: Survival among people with early-onset (diagnosed before age 50) colorectal cancer compared with later-onset colorectal cancer (diagnosed at ages 51 through 55) was compared using data from the National Cancer Database.

Authors: Charles S. Fuchs, M.D., M.P.H., of the Yale School of Public Health in New Haven, Connecticut, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12539)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and ...

What The Study Did: This study demonstrated an association between receiving the mRNA-1273 (Moderna) vaccine and a reduction in SARS-CoV-2 infection in health care workers beginning eight days after the first dose.

Authors: Michael E. Charness, M.D., of the VA Boston Healthcare System in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16416)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest ...

A ball of 4,000-year-old hair frozen in time tangled around a whalebone comb led to the first ever reconstruction of an ancient human genome just over a decade ago.

The hair, which was preserved in arctic permafrost in Greenland, was collected in the 1980s and stored at a museum in Denmark. It wasn't until 2010 that evolutionary biologist Professor Eske Willerslev was able to use pioneering shotgun DNA sequencing to reconstruct the genetic history of the hair.

He found it came from a man from the earliest known people to settle in Greenland ...

Stimulation of the nervous system with neurotechnology has opened up new avenues for treating human disorders, such as prosthetic arms and legs that restore the sense of touch in amputees, prosthetic fingertips that provide detailed sensory feedback with varying touch resolution, and intraneural stimulation to help the blind by giving sensations of sight.

Scientists in a European collaboration have shown that optic nerve stimulation is a promising neurotechnology to help the blind, with the constraint that current technology has the capacity of providing only simple visual signals.

Nevertheless, the scientists' vision (no pun intended) is to design these simple visual signals to be meaningful in assisting the blind with daily living. Optic nerve stimulation ...

Although plexiglass barriers are seemingly everywhere these days -- between grocery store lanes, around restaurant tables and towering above office cubicles -- they are an imperfect solution to blocking virus transmission.

Instead of capturing virus-laden respiratory droplets and aerosols, plexiglass dividers merely deflect droplets, causing them to bounce away but remain in the air. To enhance the function of these protective barriers, Northwestern University researchers have developed a new transparent material that can capture droplets and aerosols, effectively ...

New York, NY (June 16, 2021) -- Immune cells that normally repair tissues in the body can be fooled by tumors when cancer starts forming in the lungs and instead help the tumor become invasive, according to a surprising discovery reported by Mount Sinai scientists in Nature in June.

The researchers found that early-stage lung cancer tumors coopt the immune cells, known as tissue-resident macrophages, to help invade lung tissue. They also mapped out the process, or program, of how the macrophages allows a tumor to hurt the tissues the macrophage normally repairs. This process allows the tumor to hide from the immune system and proliferate into later, deadly stages of cancer.

Macrophages play a key ...

June 16, 2021, CLEVELAND: New findings from Cleveland Clinic researchers show for the first time that the gut microbiome impacts stroke severity and functional impairment following stroke. The results, published in Cell Host & Microbe, lay the groundwork for potential new interventions to help treat or prevent stroke.

The research was led by Weifei Zhu, Ph.D., and Stanley Hazen, M.D., Ph.D., of Cleveland Clinic's Lerner Research Institute. The study builds on more than a decade of research spearheaded by Dr. Hazen and his team related to the gut microbiome's role in cardiovascular health and disease, including the adverse effects of TMAO (trimethylamine N-oxide) - a byproduct produced when gut bacteria digest certain nutrients abundant in red meat and other animal ...