(Press-News.org) The role of people infected with malaria without showing symptoms presents a hidden risk to efforts to control the disease after they were found to be responsible for most infections in mosquitoes, according to a study published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

Researchers from the Infectious Diseases Research Collaboration (IDRC), London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), Radboud university medical center and University of California, San Francisco, found asymptomatic children in the Uganda study were the biggest source of malaria parasites transmitted to mosquitoes. This could provide a new opportunity for control efforts by targeting this infectious reservoir.

Malaria presents a major health threat globally, with 94% of cases on the African continent alone, according to the WHO World Malaria Report 2020. The disease is passed to a human through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito causing infection with the parasite. The predominant and most deadly parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, accounts for over 75% of mortality worldwide and is highly prevalent in Uganda.

Malarial parasites depend on a life cycle in which they constantly move back and forth between humans and mosquitoes. Successfully interrupting transmission of the disease can involve clearing parasites from human 'hosts' using anti-malaria drugs.

Nagongera sub-county (Tororo district) in eastern Uganda has historically very high malaria transmission but following intensive malaria control efforts, such as insecticide-treated bednets, indoor residual spraying (IRS) with insecticides and access to malaria drugs, infections - or at least symptomatic cases - have gone down remarkably.

The research team aimed to investigate patterns of malaria infection and understand more about transmission in the area. The study involved two years of regularly testing more than 500 people for evidence of malaria parasites. The genetic make-up of parasites was determined, as well as their ability to infect mosquitoes.

The researchers found that individuals who were asymptomatic were unknowingly responsible for most mosquito infections in the study. People with symptomatic infections were responsible for less than 1% of mosquito infections and appeared to play a negligible role in sustaining transmission.

School-aged children aged 5-15 years were responsible for over half (59%) of the infectious reservoir, followed by the under-5s (26%) and people aged 16 years and older (16%). Surprisingly, the researchers found just four children were linked to 60% of the infected mosquitoes studied.

Co-author Dr John Rek from IDRC said: "These findings are a real eye opener in the fight against malaria. We found that infections in school-aged children drive malaria transmission. Some children harboured billions of malaria parasites in their bloodstream without experiencing symptoms."

LSHTM co-author Professor Sarah Staedke said: "School-aged children are an important reservoir of malaria parasites that could be easily targeted for control interventions, such as chemoprevention through intermittent preventive treatment.

"This would benefit individual children, may reduce malaria transmission, and could help sustain malaria gains if intense vector control measures are interrupted."

Understanding transmission among asymptomatic cases is particularly important in areas where malaria control has been successful, but there is a risk that malaria might resurge when control measures are relaxed or withdrawn. Asymptomatic children that keep malaria circulating at relatively low levels could be sufficient to cause infections to quickly rebound if control efforts are not maintained. In other parts of Uganda, when intense malaria control with indoor residual spraying was halted, infections rebounded within weeks.

Principal author Professor Teun Bousema, from Radboud university medical center, said: "Our study demonstrates that even when malaria appears under control, there is a reservoir of infected individuals who can sustain the spread of this deadly disease. Unless their infections are targeted, malaria can quickly return."

Overall, these findings provide evidence that asymptomatic infections are an important source of onward transmission to mosquitoes. Many malaria infections that contribute to transmission are initially below the level detectable by conventional diagnostic tests, including microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests.

Professor Moses Kamya, IDRC co-author of the study, said: "Only through focused interventions, ideally supplemented by highly sensitive testing, can we target the reservoirs of infection in school-age children."

The study authors acknowledge limitations of the study including the length of time between participant sample selection and mosquito feeds, meaning they did not routinely measure infectiousness in the first few weeks of asymptomatic infections. They also noted that trial participants had exceptionally good access to care whereas in other settings people with symptomatic malaria infections might develop more transmissible infections if treatment is not administered quickly.

INFORMATION:

The study was funded by the US National Institutes of Health, with additional support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the European Research Council.

Notes to Editors

For more information or interview requests, please contact press@lshtm.ac.uk.

A copy of the embargoed paper is available upon request. Once published the paper will be available here: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(21)00072-4/fulltext

Publication:

C. Andolina et al. Sources of persistent malaria transmission in a setting with effective malaria control in eastern Uganda: a longitudinal, observational cohort study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. DOI: 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00072-4

London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) is a world-leading centre for research, postgraduate studies and continuing education in public and global health. LSHTM has a strong international presence with over 3,000 staff and 4,000 students working in the UK and countries around the world, and an annual research income of £180 million.

LSHTM is one of the highest-rated research institutions in the UK, is partnered with two MRC University Units in The Gambia and Uganda, and was named University of the Year in the Times Higher Education Awards 2016. Our mission is to improve health and health equity in the UK and worldwide; working in partnership to achieve excellence in public and global health research, education and translation of knowledge into policy and practice.

http://www.lshtm.ac.uk

Corticosteroids may be an effective treatment for children who develop a rare but serious condition after COVID-19 infection.

This is the finding of an international study of 614 children, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, led by Imperial College London.

All children in the study developed a serious disorder following COVID-19 infection. This condition, called multi-system inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), is thought to affect 1 in 50,000 children with SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The new disorder, which is also called paediatric inflammatory multi-system syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection (PIMS-TS), affects children of all ages but is more common in older children ...

During the first several months of the pandemic -- when communities locked down, jobs were lost, PPE was scarce and store shelves were cleared --thousands of people turned to online crowdfunding to meet their needs.

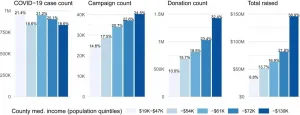

But a new University of Washington analysis of requests and donations to the popular crowdfunding site GoFundMe, along with Census data, shows stark inequities in where the money went and how much was donated.

A study published June 15 in Social Science & Medicine found more than 175,000 COVID-19-related GoFundMe campaigns in the U.S., raising more than $416 million, from January through July 2020. Researchers found that affluent and educated ...

'God forbid we need this, but we'll be ready'

Medication would be taken early in the disease, so you don't get as sick

Future drug could also treat common cold

CHICAGO --- Scientists are already preparing for a possible next coronavirus pandemic to strike, keeping with the seven-year pattern since 2004.

In future-looking research, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine scientists have identified a novel target for a drug to treat SARS-CoV-2 that also could impact a new emerging coronavirus.

"God forbid we need this, but we will be ready," said Karla Satchell, professor of microbiology-immunology at Feinberg, who leads an international team of scientists to analyze the important structures of the virus. The Northwestern team previously ...

An innovative underwater robot known as Mesobot is providing researchers with deeper insight into the vast mid-ocean region known as the "twilight zone." Capable of tracking and recording high-resolution images of slow-moving and fragile zooplankton, gelatinous animals, and particles, Mesobot greatly expands scientists' ability to observe creatures in their mesopelagic habitat with minimal disturbance. This advance in engineering will enable greater understanding of the role these creatures play in transporting carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to the deep sea, as well as how commercial exploitation of twilight ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Human-caused wildfire ignitions in Central Oregon are expected to remain steady over the next four decades and lightning-caused ignitions are expected to decline, but the average size of a blaze from either cause is expected to rise, Oregon State University modeling suggests.

Scientists including Meg Krawchuk of the OSU College of Forestry and former OSU research associate Ana Barros, now of the Washington Department of Natural Resources, say the findings can help local decision-makers understand how a changing climate might affect natural and human-caused fire regimes differently and inform ...

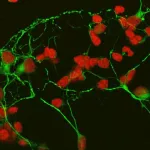

Researchers at the National Eye Institute (NEI) have determined how certain short protein fragments, called peptides, can protect neuronal cells found in the light-sensing retina layer at the back of the eye. The peptides might someday be used to treat degenerative retinal diseases, such as age-related macular degeneration (AMD). The study published today in the Journal of Neurochemistry. NEI is part of the National Institutes of Health.

A team led by Patricia Becerra, Ph.D., chief of the NEI Section on Protein Structure and Function, had previously derived these peptides from a protein called pigment epithelium-derived ...

A study of young immigrant mothers who are survivors of sex trafficking found that the trauma affected how they parented: it made them overprotective parents in a world perceived to be unsafe, it fueled emotional withdrawal when struggling with stress and mental health symptoms, and was a barrier to building confidence as mothers. Yet, they coped with such challenges finding meaning in the birth of their child and through social support and faith.

Results of the community-based participatory research study by researchers at Columbia University ...

An alternate-day intermittent fasting schedule offered less fat-reducing benefits than a matched "traditional" diet that restricts daily energy intake, according to a new, 3-week randomized trial involving 36 participants. The study, which is one of the first to tease apart the effects of fasting and daily energy restriction in lean individuals, indicates that alternate-day fasting may offer no fasting-specific health or metabolic benefits over a standard daily diet. However, the authors caution that longer studies with larger groups are needed. Intermittent fasting, which involves cycling through voluntary fasting and non-fasting periods, has become one of the most popular approaches to losing weight. There ...

We've seen robots take to the air, dive beneath the waves and perform all sorts of maneuvers on land. Now, researchers at UC Santa Barbara and Georgia Institute of Technology are exploring a new frontier: the ground beneath our feet. Taking their cues from plants and animals that have evolved to navigate subterranean spaces, they've developed a fast, controllable soft robot that can burrow through sand. The technology not only enables new applications for fast, precise and minimally invasive movement underground, but also lays mechanical foundations for new types of robots.

"The biggest challenges with moving through the ground ...

In a study of more than 10,600 adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19, women had significantly lower odds than men of in-hospital mortality. They also had fewer admissions to the intensive care unit and less need for mechanical ventilation. Women also had significantly lower odds of major adverse events, including acute cardiac injury, acute kidney injury, and venous thromboembolism, according to an article in the peer-reviewed Journal of Women's Health. Click here to read the article now.

"This comprehensive analysis is the largest study to date that directly assesses the impact of sex on COVID-19 outcomes," ...