(Press-News.org) Since 2005, the guidelines for the care of unconscious cardiac arrest patients have been to cool the body temperature down to 33 degrees Celsius. A large, randomised clinical trial led by Lund University and Region Skåne in Sweden has shown that this treatment does not improve survival. The study is published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

"These results will affect the current guidelines", says Niklas Nielsen, researcher at Lund University and consultant in anaesthesiology and intensive care at Helsingborg Hospital, who led the study.

In the early 2000s, two studies in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that induced hypothermia in unconscious cardiac arrest patients greatly improved patient survival. The studies changed existing treatment practices, and led to the introduction of new guidelines around the world. However, the evidence for the guidelines was considered by many to be weak. As a result, a large international randomised clinical trial was initiated, and led by researchers at Lund University and Helsingborg Hospital.

The results of the comprehensive study, which has now been published in the same journal, show that hypothermia does not reduce mortality in unconscious patients with suspected cardiac arrest.

"It is important to set high standards for clinical studies, partly to determine what should be introduced in healthcare, partly to challenge the practices that are already in use - to ensure that we have got it right and that healthcare is evidence-based. The results produced strongly indicate that normal temperature should be recommended, not hypothermia", says Niklas Nielsen.

In total, 1900 adult patients who suffered cardiac arrest and were unconscious when admitted to hospital were included in the study. Between November 2017 and January 2020, a total of 61 hospitals around the world participated in the study which has now been published. The patients included in the study had suffered unexpected out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

The patients were randomised into two groups when they were admitted to hospital. In one group, the patients were cooled down to 33 degrees according to existing guidelines, a temperature that was maintained for 28 hours. In the second group, the patient's body temperature was monitored, and the patients who developed a fever (about half of the participants in this group) were treated with the same method of temperature control, but kept at a normal temperature. The study was ethically approved in participating countries.

Researchers followed up on survival rates for patients six months after receiving care for cardiac arrest. They also investigated how functionality in everyday life was affected in the surviving patients.

1850 patients were included in the survival analysis*. Six months after the patients suffered the cardiac arrest, a total of 465 of 925 participants in the group who were induced with hypothermia had died, approximately 50%. In the normothermia group, 446 out of 925 had died, corresponding to 48%. Researchers saw a slightly increased risk of impact on blood circulation, cardiac arrhythmia, in the group treated with hypothermia.

1747 patients were included in the analysis of patients' ability to function in everyday life (functional status). In the group treated with hypothermia, 488 of 881 (55%) either died or had a severe functional impairment 6 months later, which can be compared to 479 of 866 (55%) in the normothermia group.

"Since it is a large study involving many hospitals in different countries, it has been logistically challenging to follow up six months after the cardiac arrest. A dedicated effort has been put in to obtaining data. This has meant that sometimes patients have had to be visited at home, some patients have moved, and some suffered cardiac arrest in a country other than their homeland", says Gisela Lilja, researcher at Lund University and chief occupational therapist at Skåne University Hospital, who coordinated the follow-up in the study.

"The results are important, but not unexpected. For 20 years we have applied and believed in these practices which we now see do not make a difference for survival. Now we can use the resources on other things, and prioritise other aspects of the acute phase of cardiac arrest", says Josef Dankiewicz, researcher at Lund University and resident physician at Skåne University Hospital, and first author of the study.

Researchers now plan to further analyse patient data to learn more about who is affected, and about recovery after cardiac arrest.

* 36 patients declined to be part of the study, and there is data missing on 11 participants (6 in the hypothermia group and 5 in the other group)

INFORMATION:

Conservationists have long warned of the dangers associated with bears becoming habituated to life in urban areas. Yet, it appears the message hasn't gotten through to everyone.

News reports continue to cover seemingly similar situations -- a foraging bear enters a neighbourhood, easily finds high-value food and refuses to leave. The story often ends with conservation officers being forced to euthanize the animal for public safety purposes.

Now, a new study by sustainability researchers in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science uses computer modelling to look at the best strategies to reduce human-bear conflict.

"It happens all the time, and unfortunately, humans are almost ...

Research shows that inhibiting necroptosis, a form of cell death, could be a novel therapeutic approach for treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), an inflammatory lung condition, also known as emphysema, that makes it difficult to breathe.

Published in the prestigious American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, the study by a team of Australian and Belgian researchers, revealed elevated levels of necroptosis in patients with COPD.

By inhibiting necroptosis activity, both in the lung tissue of COPD patients as well as ...

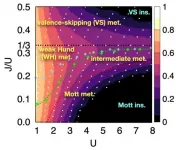

Electrons are ubiquitous among atoms, subatomic tokens of energy that can independently change how a system behaves--but they also can change each other. An international research collaboration found that collectively measuring electrons revealed unique and unanticipated findings. The researchers published their results on May 17 in Physical Review Letters.

"It is not feasible to obtain the solution just by tracing the behavior of each individual electron," said paper author Myung Joon Han, professor of physics at KAIST. "Instead, one should describe or track all the entangled electrons at once. This requires a clever way of treating this entanglement."

Professor Han and the researchers used a recently developed "many-particle" theory to account for the ...

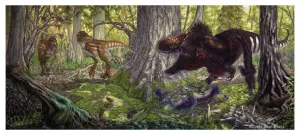

New UMD study suggests that everywhere tyrannosaurs rose to dominance, their juveniles took over the ecological role of medium-sized carnivores

A new study shows that medium-sized predators all but disappeared late in dinosaur history wherever Tyrannosaurus rex and its close relatives rose to dominance. In those areas--lands that eventually became central Asia and Western North America--juvenile tyrannosaurs stepped in to fill the missing ecological niche previously held by other carnivores.

The research conducted by Thomas Holtz, a principal lecturer in ...

Like the movie version of Spider-Man who shoots spider webs from holes in his wrists, a little alpine plant has been found to eject cobweb-like threads from tiny holes in specialised cells on its leaves. It's these tiny holes that have taken plant scientists by surprise because puncturing the surface of a plant cell would normally cause it to explode like a water balloon.

The small perennial cushion-shaped plant with bright yellow flowers, Dionysia tapetodes, is in the primula family and naturally occurs in Turkmenistan and north-eastern Iran, and through the mountains of Afghanistan to the border of Pakistan. What makes it unusual is its leaves, which are covered in long silky fibres that ...

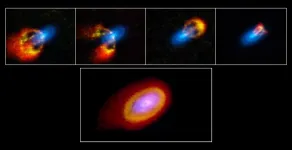

A team of scientists using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to study the young star Elias 2-27 have confirmed that gravitational instabilities play a key role in planet formation, and have for the first time directly measured the mass of protoplanetary disks using gas velocity data, potentially unlocking one of the mysteries of planet formation. The results of the research are published today in two papers in The Astrophysical Journal.

Protoplanetary disks--planet-forming disks made of gas and dust that surround newly formed young stars--are ...

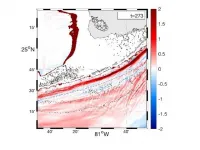

Ocean currents sometimes pinch off sections that create circular currents of water called "eddies." This "whirlpool" motion moves nutrients to the water's surface, playing a significant role in the health of the Florida Keys coral reef ecosystem.

Using a numerical model that simulates ocean currents, researchers from Florida Atlantic University's Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute and collaborators from the Alfred-Wegener-Institute in Germany and the Institut Universitaire Europeen De La Mer/Laboratoire d'Océonographie Physique et Spatiale in France are shedding light on this important "motion of the ocean." They have conducted a first-of-its-kind study identifying ...

Researchers at the National Institutes of Health have developed a prototype device that could potentially diagnose pregnancy complications by monitoring the oxygen level of the placenta. The device sends near-infrared light through the pregnant person's abdomen to measure oxygen levels in the arterial and venous network in the placenta. The method was used to study anterior placenta, which is attached to the front wall of the uterus. The researchers described their results as promising but added that further study is needed before the device could be used routinely.

The small study was conducted by Amir Gandjbakhche, Ph.D., of the Section on Translational Biophotonics at NIH's Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute ...

People--who get lost easily in the extraordinary darkness of a tropical forest--have much to learn from a bee that can find its way home in conditions 10 times dimmer than starlight. Researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute's (STRI) research station on Barro Colorado Island in Panama and the University of Lund in Sweden reveal that sweat bees (Megalopta genalis), find their way home based on patterns in the canopy overhead using dorsal vision. This first report of dorsal navigation in a flying insect, published in Current Biology, may be of special interest to makers of drones and other night-flying vehicles.

"One of the pioneers of studies on homing behaviors in bees was Charles H. Turner, an African-American scientist from the University ...

Bacteria do not sexually reproduce, but that does not stop them from exchanging genetic information as it evolves and adapts. During conjugal transfer, a bacterium can connect to another bacterium to pass along DNA and proteins. Escherichia coli bacteria, commonly called E. coli, can transfer at least one of these gene-containing plasmids to organisms across taxonomic kingdoms, including to fungi and protists. Now, researchers from Hiroshima University have a better understanding of this genetic hat trick, which has potential applications as a tool to promote desired characteristics or suppress harmful ones across genetic hosts.

They published their results on ...