(Press-News.org) African American mothers continue to have the lowest breastfeeding rates, even as the breastfeeding rates have risen in the U.S. over the past 25 years. Racism is an important barrier to breastfeeding, as examined in Part 2 of a special issue on "Breastfeeding and the Black/African American Experience: Cultural, Sociological, and Health Dimensions Through an Equity Lens," published in the peer-reviewed journal Breastfeeding Medicine. Click here to read the issue now.

The special issue is led by Guest Editor Sahira Long, MD, a pediatrician and lactation consultant.

Exploring how racism creates barriers to breastfeeding for Black mothers and how Black women resist racism during their quest to breastfeed are Catasha Davis, PhD and Aubrey Van Kirk Villalobos, DrPH, Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University, and coauthors. In their article, the authors identify three forms of institutionalized racism as significant barriers to breastfeeding: the historic exploitation of Black women's labor; institutions pushing formula on Black mothers; and lack of economic and employer-based support.

"Institutional support for breastfeeding from employers and hospitals is an essential ingredient for countering institutionalized racism," state the authors.

In the article "Reimagining Racial Trauma as a Barrier to Breastfeeding versus Childhood Trauma and Depression among African American Mothers," Maria Muzik, MD, Michigan Medicine and colleagues examined the relationship between several maternal risk factors and breastfeeding status at 6-months postpartum.

"We found that African American mothers had reduced rates of breastfeeding at 6 months, above and beyond all the other risk factors in the model," said the researchers.

Arthur I. Eidelman, MD, Editor-in-Chief of Breastfeeding Medicine, states: "This two-part Special Issue addresses the multiple facets of this ongoing public health crisis, and will assist in mobilizing our nation's resources in remedying the consequences of institutionalized racism."

INFORMATION:

About the Journal

Breastfeeding Medicine, the official journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine, is an authoritative, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary journal published 10 times per year in print and online. The Journal publishes original scientific papers, reviews, and case studies on a broad spectrum of topics in lactation medicine. It presents evidence-based research advances and explores the immediate and long-term outcomes of breastfeeding, including the epidemiologic, physiologic, and psychological benefits of breastfeeding. Tables of content and a sample issue may be viewed on the Breastfeeding Medicine website.

About the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine (ABM) is a worldwide organization of medical doctors dedicated to the promotion, protection, and support of breastfeeding. Our mission is to unite members of the various medical specialties with this common purpose. For more than 20 years, ABM has been bringing doctors together to provide evidence-based solutions to the challenges facing breastfeeding across the globe. A vast body of research has demonstrated significant nutritional, physiological, and psychological benefits for both mothers and children that last well beyond infancy. But while breastfeeding is the foundation of a lifetime of health and well-being, clinical practice lags behind scientific evidence. By building on our legacy of research into this field and sharing it with the broader medical community, we can overcome barriers, influence health policies, and change behaviors.

About the Publisher

Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers is known for establishing authoritative peer-reviewed journals in many promising areas of science and biomedical research. A complete list of the firm's 90 journals, books, and newsmagazines is available on the Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publisher's website.

Since 2005, the guidelines for the care of unconscious cardiac arrest patients have been to cool the body temperature down to 33 degrees Celsius. A large, randomised clinical trial led by Lund University and Region Skåne in Sweden has shown that this treatment does not improve survival. The study is published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

"These results will affect the current guidelines", says Niklas Nielsen, researcher at Lund University and consultant in anaesthesiology and intensive care at Helsingborg Hospital, who led the study.

In the early 2000s, two studies in the New England Journal of Medicine showed that induced hypothermia in unconscious cardiac arrest patients ...

Conservationists have long warned of the dangers associated with bears becoming habituated to life in urban areas. Yet, it appears the message hasn't gotten through to everyone.

News reports continue to cover seemingly similar situations -- a foraging bear enters a neighbourhood, easily finds high-value food and refuses to leave. The story often ends with conservation officers being forced to euthanize the animal for public safety purposes.

Now, a new study by sustainability researchers in the Irving K. Barber Faculty of Science uses computer modelling to look at the best strategies to reduce human-bear conflict.

"It happens all the time, and unfortunately, humans are almost ...

Research shows that inhibiting necroptosis, a form of cell death, could be a novel therapeutic approach for treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), an inflammatory lung condition, also known as emphysema, that makes it difficult to breathe.

Published in the prestigious American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, the study by a team of Australian and Belgian researchers, revealed elevated levels of necroptosis in patients with COPD.

By inhibiting necroptosis activity, both in the lung tissue of COPD patients as well as ...

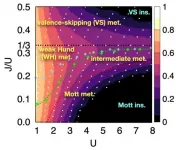

Electrons are ubiquitous among atoms, subatomic tokens of energy that can independently change how a system behaves--but they also can change each other. An international research collaboration found that collectively measuring electrons revealed unique and unanticipated findings. The researchers published their results on May 17 in Physical Review Letters.

"It is not feasible to obtain the solution just by tracing the behavior of each individual electron," said paper author Myung Joon Han, professor of physics at KAIST. "Instead, one should describe or track all the entangled electrons at once. This requires a clever way of treating this entanglement."

Professor Han and the researchers used a recently developed "many-particle" theory to account for the ...

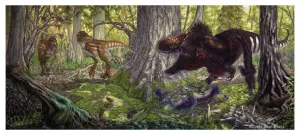

New UMD study suggests that everywhere tyrannosaurs rose to dominance, their juveniles took over the ecological role of medium-sized carnivores

A new study shows that medium-sized predators all but disappeared late in dinosaur history wherever Tyrannosaurus rex and its close relatives rose to dominance. In those areas--lands that eventually became central Asia and Western North America--juvenile tyrannosaurs stepped in to fill the missing ecological niche previously held by other carnivores.

The research conducted by Thomas Holtz, a principal lecturer in ...

Like the movie version of Spider-Man who shoots spider webs from holes in his wrists, a little alpine plant has been found to eject cobweb-like threads from tiny holes in specialised cells on its leaves. It's these tiny holes that have taken plant scientists by surprise because puncturing the surface of a plant cell would normally cause it to explode like a water balloon.

The small perennial cushion-shaped plant with bright yellow flowers, Dionysia tapetodes, is in the primula family and naturally occurs in Turkmenistan and north-eastern Iran, and through the mountains of Afghanistan to the border of Pakistan. What makes it unusual is its leaves, which are covered in long silky fibres that ...

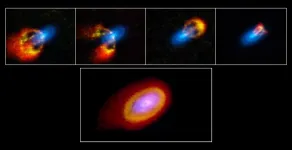

A team of scientists using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) to study the young star Elias 2-27 have confirmed that gravitational instabilities play a key role in planet formation, and have for the first time directly measured the mass of protoplanetary disks using gas velocity data, potentially unlocking one of the mysteries of planet formation. The results of the research are published today in two papers in The Astrophysical Journal.

Protoplanetary disks--planet-forming disks made of gas and dust that surround newly formed young stars--are ...

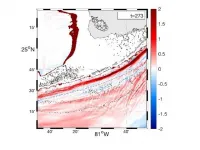

Ocean currents sometimes pinch off sections that create circular currents of water called "eddies." This "whirlpool" motion moves nutrients to the water's surface, playing a significant role in the health of the Florida Keys coral reef ecosystem.

Using a numerical model that simulates ocean currents, researchers from Florida Atlantic University's Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute and collaborators from the Alfred-Wegener-Institute in Germany and the Institut Universitaire Europeen De La Mer/Laboratoire d'Océonographie Physique et Spatiale in France are shedding light on this important "motion of the ocean." They have conducted a first-of-its-kind study identifying ...

Researchers at the National Institutes of Health have developed a prototype device that could potentially diagnose pregnancy complications by monitoring the oxygen level of the placenta. The device sends near-infrared light through the pregnant person's abdomen to measure oxygen levels in the arterial and venous network in the placenta. The method was used to study anterior placenta, which is attached to the front wall of the uterus. The researchers described their results as promising but added that further study is needed before the device could be used routinely.

The small study was conducted by Amir Gandjbakhche, Ph.D., of the Section on Translational Biophotonics at NIH's Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute ...

People--who get lost easily in the extraordinary darkness of a tropical forest--have much to learn from a bee that can find its way home in conditions 10 times dimmer than starlight. Researchers at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute's (STRI) research station on Barro Colorado Island in Panama and the University of Lund in Sweden reveal that sweat bees (Megalopta genalis), find their way home based on patterns in the canopy overhead using dorsal vision. This first report of dorsal navigation in a flying insect, published in Current Biology, may be of special interest to makers of drones and other night-flying vehicles.

"One of the pioneers of studies on homing behaviors in bees was Charles H. Turner, an African-American scientist from the University ...