(Press-News.org) BOSTON - An antibiotic developed in the 1950s and largely supplanted by newer drugs, effectively targets and kills cancer cells with a common genetic defect, laboratory research by Dana-Farber Cancer Institute scientists shows. The findings have spurred investigators to open a clinical trial of the drug, novobiocin, for patients whose tumors carry the abnormality.

In a study in the journal Nature Cancer, the researchers found that in laboratory cell lines and tumor models novobiocin selectively killed tumor cells with abnormal BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes, which help repair damaged DNA. The drug was effective even in tumors resistant to agents known as PARP inhibitors, which have become a prime therapy for cancers with DNA-repair glitches.

"PARP inhibitors represent an important advance in the treatment of cancers with defects in BRCA1, BRCA2, or other genes involved in DNA repair. By allowing tumor cells to accumulate additional genetic damage, they essentially incapacitate the cells and cause them to die," says Alan D'Andrea, MD, director of the Susan F. Smith Center for Women's Cancers and the Center for DNA Damage and Repair at Dana-Farber and co-senior author of the study with Raphael Ceccaldi, PhD, PharmD, of the Curie Institute in Paris. "They are effective for many patients, but the cancer eventually becomes resistant and begins growing again. Drugs capable of overcoming that resistance are urgently needed." D'Andrea added.

BRCA mutations - whether inherited or acquired - are found in a sizeable percentage of breast, ovarian, prostate, and pancreatic cancers. The discovery of novobiocin's effectiveness in PARP inhibitor-resistant tumors arose when two strands of research converged on a key enzyme in tumor cells.

In a study published in 2015, D'Andrea and his colleagues found that tumors with poorly functioning BRCA1 and -2 genes are overdependent for their growth and survival on an enzyme known as POLθ, or POLQ. For the new study, they screened thousands of molecules - some new, some used in approved drugs - in BRCA-deficient tumors to see if any had an effect on tumor growth. The screenings were conducted in laboratory cell lines, in organoids - three dimensional cultures of tumor tissue - and in animal models.

Of the multitude of molecules and drugs tested, one stood out for its ability to kill the tumor cells while leaving normal cells unharmed - novobiocin. The protein that novobiocin targets within cells was eminently familiar to researchers - POLQ, specifically, a portion known as the ATPase domain.

When investigators looked into the medical literature on novobiocin, they found a surprise, D'Andrea relates. Though developed and used as an antibiotic, it had been tested in the early 1990s in a clinical trial for patients with hard-to-treat cancers. While most of the patients didn't benefit from the drug, a small number had their cancer recede or stabilize.

"At the time, no one knew what the drug's target was," D'Andrea remarks. "Now we do, and, as a result, we have an indication of which patients are likely to be helped by it."

On the basis of the study results, Dana-Farber investigators will be launching a clinical trial of novobiocin for patients with BRCA-deficient cancers that have acquired resistance to PARP inhibitors. Because it is an oral drug that is safe and approved for treating another disease, novobiocin offers several advantages as an agent for study, D'Andrea comments.

"We're looking forward to testing novobiocin, alone and in combination with other agents, in patients whose tumors have molecular characteristics indicating a likely response to the drug," D'Andrea says.

INFORMATION:

The first author of the study is Jia Zhou, PhD, of Dana-Farber. Co-authors are Constantia Pantelidou, PhD, Adam Li, Anniina Farkkila, MD, PhD, Bose Kochupurakkal, PhD, and Geoffrey I. Shapiro, MD, PhD, of Dana-Farber; Camille Gelot, PhD, and Hatice Yu?cel, of the Curie Institute; Rachel E. Davis, PhD, and Brian S. J. Blagg, PhD, of the University of Notre Dame; and Aleem Syed, PhD, and John A. Tainer, PhD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

The research was supported by a Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C)-Ovarian Cancer Research Fund Alliance-National Ovarian Cancer Coalition Dream Team Translational Research Grant (SU2C-AACR-DT16-15). This work was also supported by the Richard and Susan Smith Family Foundation and the Basser Initiative at the Gray Foundation. It was also supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants R37HL052725, P01HL048546, and P50CA168504); the US Department of Defense (grants BM110181 and BC151331P1); as well as grants from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the Fanconi Anemia Research Fund, an ERC starting grant (N° 714162), and the Ville de Paris Emergences Program grant (N° DAE 137). It was also supported by an Ann Schreiber Mentored Investigator Award from the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund Alliance (457527) and a Joint Center for Radiation Therapy Award from Harvard Medical School.

About Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute is one of the world's leading centers of cancer research and treatment. Dana-Farber's mission is to reduce the burden of cancer through scientific inquiry, clinical care, education, community engagement, and advocacy. We provide the latest treatments in cancer for adults through Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women's Cancer Center and for children through Dana-Farber/Boston Children's Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. Dana-Farber is the only hospital nationwide with a top 10 U.S. News & World Report Best Cancer Hospital ranking in both adult and pediatric care.

As a global leader in oncology, Dana-Farber is dedicated to a unique and equal balance between cancer research and care, translating the results of discovery into new treatments for patients locally and around the world, offering more than 1,100 clinical trials.

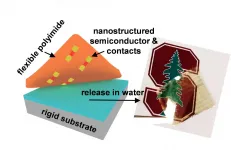

Ultrathin, flexible computer circuits have been an engineering goal for years, but technical hurdles have prevented the degree of miniaturization necessary to achieve high performance. Now, researchers at Stanford University have invented a manufacturing technique that yields flexible, atomically thin transistors less than 100 nanometers in length - several times smaller than previously possible. The technique is detailed in a paper published June 17 in Nature Electronics.

With the advance, said the researchers, so-called "flextronics" move closer to reality. Flexible electronics promise bendable, ...

PHILADELPHIA-- The COVID-19 death rate for Black patients would be 10 percent lower if they had access to the same hospitals as white patients, a new study shows. Researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and OptumLabs, part of UnitedHealth Group, analyzed data from tens of thousands of hospitalized COVID-19 patients and found that Black patients died at higher rates than white patients. But the study, published today in JAMA Network Open, determined that didn't have to be the case if more Black patients were able to get care at different hospitals.

"Our study reveals that Black patients have worse outcomes largely because they tend to go to worse-performing hospitals," said the study's first author, David Asch, MD, ...

What The Study Did: The findings of this study suggest that the increased mortality among Black patients hospitalized with COVID-19 is associated with the hospitals at which Black patients disproportionately received care.

Authors: David A. Asch, M.D., M.B.A., of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is the the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.12842)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, ...

What The Study Did: Researchers evaluated the association of convalescent plasma treatment with 30-day mortality in hospitalized adults with hematologic (blood) cancers and COVID-19.

Authors: Jeremy L.Warner, M.D., M.S., of Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2021.1799)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please ...

What The Study Did: This study examined whether mandatory daily employee symptom data collection can be used as an early alert surveillance system to estimate COVID-19 hospitalizations in communities where employees live.

Authors: Steven Horng, M.D., M.MSc., of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, is the the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13782)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study ...

What The Study Did: In this survey study, COVID-19 was associated with large reductions in economic security among women at high risk of HIV infection in Kenya. However, shifts in sexual behavior may have temporarily decreased their risk of HIV infection.

Authors: Harsha Thirumurthy, Ph.D., of the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, is the the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13787)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, ...

What The Study Did: Researchers estimated survival and other outcomes of very preterm infants in China discharged against medical advice from neonatal intensive care units before complete care can be provided compared with infants who receive full intensive care treatment.

Authors: Yun Cao, M.D., Ph.D., and Weili Yan, Ph.D., of Children's Hospital of Fudan University in Shanghai, China, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13197)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest ...

The 'Xpert Ultra' molecular test has a greater capacity than its predecessor ('Xpert MTB/RIF') in detecting tuberculosis cases, either passively (i.e. people who attend the hospital with disease symptoms) or actively (searching for possible cases in the community among contacts of cases). This is the main conclusion of a study performed by ISGlobal, an institution supported by "la Caixa" Foundation, in collaboration with the Manhiça Health Research Centre (CISM), published in the European Respiratory Journal.

Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death by an infectious agent, worldwide. In 2019, 1.4 million people are estimated to have died and 10 million people fell sick from TB, although only 70% of the cases were diagnosed. ...

Scientists have identified a new class of targeted cancer drugs that offer the potential to treat patients whose tumours have faulty copies of the BRCA cancer genes.

The drugs, known as POLQ inhibitors, specifically kill cancer cells with mutations in the BRCA genes while leaving healthy cells unharmed.

And crucially, they can kill cancer cells that have become resistant to PARP inhibitors - an existing treatment for patients with BRCA mutations.

Researchers are already planning to test the new drug class in upcoming clinical trials. If the trials are successful, POLQ inhibitors could enter the clinic as a new approach to treating a range of cancers with BRCA ...

Many diseases caused by a dysregulated immune system, such as allergies, asthma and autoimmunity, can be traced back to events in the first few months after birth. To date, the mechanisms behind the development of the immune system have not been fully understood. Now, researchers at Karolinska Institutet show a connection between breast milk, beneficial gut bacteria and the development of the immune system. The study is published in Cell.

"A possible application of our results is a preventative method for reducing the risk of allergies, asthma and autoimmune disease later in life by helping the immune system to establish its regulatory mechanisms," says the paper's last author Petter Brodin, paediatrician and researcher at the Department of Women's and Children's ...