Researchers discover how the intestinal epithelium folds and moves by measuring forces

2021-06-21

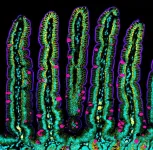

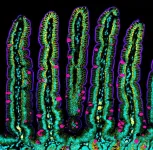

(Press-News.org) The human intestine is made up of more than 40 square meters of tissue, with a multitude of folds on its internal surface that resemble valleys and mountain peaks in order to increase the absorption of nutrients. The intestine also has the unique characteristic of being in a continuous state of self-renewal. This means that approximately every 5 days all the cells of its inner walls are renewed to guarantee correct intestinal function. Until now, scientists knew that this renewal could take place thanks to stem cells, which are protected in the so-called intestinal crypts, and which give rise to new differentiated cells. However, the process that leads to the concave shape of the crypts and the migration of new cells towards the intestinal peaks was unknown.

Now, an international team led by Xavier Trepat, ICREA Research Professor and Group Leader at the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC), in collaboration with the IRB, researchers from the UB and UPC universities in Barcelona, and the Curie Institute of Paris, has deciphered the mechanisms leading the crypts to adopt and maintain their concave shape, and how the migration movement of the cells towards the peaks occurs, without the intestine losing its characteristic folded shape. The study, published in the prestigious journal Nature Cell Biology, has combined computer modelling, led by Marino Arroyo, professor at the UPC, researcher associated with IBEC and member of CIMNE, with experiments with intestinal organoids from mouse cells, and shows that this process is possible thanks to the mechanical forces exerted by the cells. An important part of this study has been supported by the "la Caixa" Foundation within the framework of the CaixaResearch programme. The entity has also awarded a scholarship to the first co-author, Gerardo Ceada, to carry out his PhD at IBEC.

The forces determine and control the shape of the intestine and the movement of the cells

Using mouse stem cells and bioengineering and mechanobiology techniques, researchers have developed mini-intestines, organoids that resemble the three-dimensional structure of peaks and valleys, recapitulating tissue functions in vivo. Using microscopy technologies developed by the same group, researchers carried out high-resolution experiments for the first time that have allowed them to obtain 3D maps showing the forces exerted by each cell.

In addition, with this in vitro model, scientists have shown that the movement of new cells to the peak is also controlled by mechanical forces exerted by the cells themselves, specifically by the cytoskeleton, a network of filaments that determines and maintains cell shape.

"Contrary to what was believed up until now, we have been able to determine that it is not the cells of the intestinal crypt that push the new ones up, but that it is the cells at the peak pulling the new ones up, akin to a mountaineer who helps another climber by pulling them up", explains Gerardo Ceada from IBEC

"With this system, we have discovered that the crypt is concave because the cells have more tension on their upper surface than on the bottom, which causes them to adopt a conical shape. When this occurs in several cells next to each other, the result is that the tissue folds, giving rise to a pattern of peaks and valleys", adds Carlos Perez-Gonzalez, (IBEC and Curie Institute).

The new mini-intestine model will allow further studies of diseases such as cancer, celiac disease or colitis to be conducted in reproducible and real conditions, in which there is an uncontrolled proliferation of stem cells or a destructuring of the folds. In addition, intestinal organoids can be manufactured with human cells and used for the development of new drugs or for the study of the intestinal microbiota.

INFORMATION:

Note:

X. Trepat is a member of the Biomedical Research Networking Center in Bioengineering, Biomaterials and?Nanomedicine (CIBER-BBN), and Research Professors at the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA).

About the IBEC

The Bioengineering Institute of Catalonia (IBEC) is a CERCA center, it has been twice named a "Severo Ochoa Center of Excellence" and has received the TECNIO seal as a technology developer and facilitator to companies. IBEC is a member of the Barcelona Institute of Science and Technology (BIST) and carries out multidisciplinary research of excellence on the boundary between engineering and life sciences to generate knowledge, integrating fields such as nanomedicine, biophysics, biotechnology, tissue engineering and information technology applications in the healthcare field. IBEC was created in 2005 by the Catalonian Government, the University of Barcelona (UB) and the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC).

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-21

Extreme heat waves in urban areas are much more likely than previously thought, according to a new modeling approach designed by researchers including University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE) assistant professor Lei Zhao and alumnus Zhonghua Zheng (MS 16, PhD 20). Their paper with co-author Keith W. Oleson of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, "Large model structural uncertainty in global projections of urban heat waves," is published in the journal Nature Communications.

Urban heat waves (UHWs) can be devastating; a 1995 heat wave in Chicago caused more than 1,000 deaths. Last year's heat wave on the west coast caused wildfires. ...

2021-06-21

In a new publication from Opto-Electronic Advances; DOI https://doi.org/10.29026/oea.2021.200006, Researchers led by Professor Junsuk Rho from Pohang University of Science and Technology (POSTECH), South Korea consider switchable diurnal radiative cooling by doped VO2.

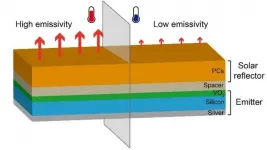

As the impacts of climate change are increasingly felt, thermoregulation technologies that do not consume external energy have attracted considerable attention in the field of energy-saving applications. Radiative cooling has received much research interest for its ability to cool an object even under direct solar illumination. Nanostructured materials, or multi-stacked layers, can be designed to control reflection and emission spectrum ...

2021-06-21

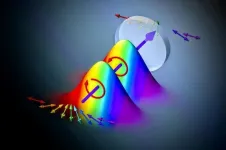

Researchers at Tampere University and their collaborators have shown how spectroscopic measurements can be made much faster. By correlating polarization to the colour of a pulsed laser, the team can track changes in the spectrum of the light by simple and extremely fast polarization measurements. The method opens new possibilities to measure spectral changes on a nanosecond time scale over the entire colour spectrum of light.

In spectroscopy, often the changes of the wavelength, i.e. colour, of a probe light are measured after interaction with a sample. Studying these changes is one of the key methods to gain a deeper understanding of the properties ...

2021-06-21

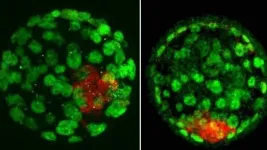

Biologists at the Universities of Bath and Vienna have discovered 71 new 'imprinted' genes in the mouse genome, a finding that takes them a step closer to unravelling some of the mysteries of epigenetics - an area of science that describes how genes are switched on (and off) in different cells, at different stages in development and adulthood.

To understand the importance of imprinted genes to inheritance, we need to step back and ask how inheritance works in general. Most of the thirty trillion cells in a person's body contain genes that come from both their mother and father, with each parent contributing one version of each gene. The unique combination of genes goes part of ...

2021-06-21

Fat biomolecules in the blood, called "serum lipids," are necessary evils. They play important roles in the lipid metabolism and are integral for the normal functioning of the body. However, they have a darker side; according to several studies, they are associated with various cancers. The medical community has fathoms to go before truly understanding the implications of different serum lipid levels in cancer.

As a major step in this direction, a group of scientists from the Key Laboratory of Carcinogenesis and Translational Research, Laboratory of Genetics, Peking University Cancer Hospital and Institute; Hua County People's Hospital; and Anyang Cancer Hospital, have successfully determined that a family history ...

2021-06-21

(BOSTON) - Research collaborators from the VA, Boston University, and the Concussion Legacy Foundation (CLF) published an inspiring new report today, "1,000 Reasons for Hope," which exclusively details the first 1,000 brain donors studied at the VA-BU-CLF Brain Bank since 2008 and how they have advanced research on concussions and CTE. The report also explains how the next 1,000 brain donors will answer critical questions that take us closer to preventing, diagnosing, and treating CTE, as well as the long-term consequences of concussion and traumatic brain injury.

"Our understanding ...

2021-06-21

Johan Gaume, an EPFL expert in avalanches and geomechanics, has turned his attention to ice. His goal is to better understand the correlation between the size of an iceberg and the amplitude of the tsunami that results from its calving. Gaume, along with a team of scientists from other research institutes, has just unveiled a new method for modeling these events. Their work appears in Communications Earth & Environment, a new journal from Nature Research.

These scientists are the first to simulate the phenomena of both glacier fracture and wave formation when the iceberg falls into the water. "Our goal was to model the explicit interaction between water and ice - but that has a substantial cost in terms of computing time. We therefore decided ...

2021-06-21

An increasing number of studies on artificial intelligence (AI) are published in the dental and oral sciences but aspects of these studies suffer from a range of limitations. Standards towards reporting, like the recently published CONSORT-AI extension, can help to improve studies in this emerging field. Watch authors Falk Schwendicke and Joachim Krois of the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany, discuss the Journal of Dental Research (JDR) article "Better Reporting of Studies on Artificial Intelligence: CONSORT-AI and Beyond," moderated by JDR Editor-in-Chief Nicholas Jakubovics, Newcastle ...

2021-06-21

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit during the winter of 2020, locking down entire countries and leaving people isolated in their homes without outside contact for weeks at a time, many relationship experts wondered what that kind of stress would do to romantic couples. What they found was that when couples blamed the pandemic for their stress, they were happier in their relationships.

The findings are outlined in a paper out today in the journal Social Psychological and Personality Science.

Previous research has shown that romantic partners tend to be more critical toward each other when experiencing ...

2021-06-21

Forces of nature have been outsmarting the materials we use to build our infrastructure since we started producing them. Ice and snow turn major roads into rubble every year; foundations of houses crack and crumble, in spite of sturdy construction. In addition to the tons of waste produced by broken bits of concrete, each lane-mile of road costs the U.S. approximately $24,000 per year to keep it in good repair.

Engineers tackling this issue with smart materials typically enhance the function of materials by increasing the amount of carbon, but doing so makes materials lose some mechanical performance. By introducing nanoparticles into ordinary cement, Northwestern University ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers discover how the intestinal epithelium folds and moves by measuring forces