(Press-News.org) Researchers have shown why people with mental health disorders, including anorexia and panic disorders, experience physical signals differently.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, found that the part of the brain which interprets physical signals from the body behaves differently in people with a range of mental health disorders, suggesting that it could be a target for future treatments.

The researchers studied 'interoception' - the ability to sense internal conditions in the body - and whether there were any common brain differences during this process in people with mental health disorders. They found that a region of the brain called the dorsal mid-insula showed different activity during interoception across a range of disorders, including depression, schizophrenia, eating disorders and anxiety disorders.

Many people with mental health disorders experience physical symptoms differently, whether that's feeling uncomfortably full in anorexia, or feeling like you don't have enough air in panic disorder.

The results, reported in The American Journal of Psychiatry, show that activity in the dorsal mid-insula could drive these different interpretations of bodily sensations in mental health. Increased awareness of the differences in how people experience physical symptoms could also be useful to those treating mental health disorders.

We all use exteroception - sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch - to navigate daily life. But interoception - the ability to interpret signals from our body - is equally important for survival, even though it often happens subconsciously.

"Interoception is something we are all doing constantly, although we might not be aware of it," said lead author Dr Camilla Nord from the MRC Cognition and Brain Sciences Unit. "For example, most of us are able to interpret the signals of low blood sugar, such as tiredness or irritability, and know to eat something. However, there are differences in how our brains interpret these signals."

Differences in interoceptive processes have previously been identified in people with eating disorders, anxiety and depression, panic disorder, addiction and other mental health disorders. Theoretical models have suggested that disrupted cortical processing drives these changes in interoceptive processing, conferring vulnerability to a range of mental health symptoms.

Nord and her colleagues combined brain imaging data from previous studies and compared differences in brain activity during interoception between 626 patients with mental health disorders and 610 healthy controls. "We wanted to find out whether there is something similar happening in the brain in people with different mental disorders, irrespective of their diagnosis," she said.

Their analysis showed that for patients with bipolar, anxiety, major depression, anorexia and schizophrenia, part of the cerebral cortex called the dorsal mid-insula showed different brain activation when processing pain, hunger and other interoceptive signals when compared to the control group.

The researchers then ran a follow-up analysis and found that the dorsal mid-insula does not overlap with regions of the brain altered by antidepressant drugs or regions altered by psychological therapy, suggesting that it could be studied as a new target for future therapeutics to treat differences in interoception.

"It's surprising that in spite of the diversity of psychological symptoms, there appears to be a common factor in how physical signals are processed differently by the brain in mental health disorders," said Nord. "It shows how intertwined physical and mental health are, but also the limitations of our diagnostic system - some important factors in mental health might be 'transdiagnostic', that is, found across many diagnoses."

In future, Dr Nord is planning studies to test whether this disrupted activation could be altered by new treatments for mental health disorders, such as brain stimulation.

INFORMATION:

The research was supported by NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and migraine often co-occur, but researchers knew relatively little about how or why this happens. A new study in Frontiers in Neuroscience is the first to investigate if the conditions have a common genetic basis. By studying identical twins, where one twin in each pair lives with PTSD or migraines and the other twin does not, the researchers found common genes that may play a role in both conditions. These genes may help to explain why the conditions co-occur, and could reveal new treatment targets for both.

PTSD is a psychiatric disorder that typically occurs after a traumatic experience, such as a life-threatening event. Most people will experience a traumatic event ...

Plastic is practical, cheap and incredibly popular. Every year, more than 350 million tonnes are produced worldwide. These plastics contain a huge variety of chemicals that may be released during their lifecycles - including substances that pose a significant risk to people and the environment. However, only a small proportion of the chemicals contained in plastic are publicly known or have been extensively studied.

A team of researchers led by Stefanie Hellweg, ETH Professor of Ecological Systems Design, has for a first time compiled a comprehensive database ...

BINGHAMTON, N.Y. -- Mental distress tends to be lower in the summer when compared to the fall, according to new research from Binghamton University, State University of New York.

"Our results suggest that summertime is associated with better diet quality, higher exercise frequency and improved mood. This is important for the post-COVID era as we are getting into the summer season," said Lina Begdache, assistant professor of health and wellness studies at Binghamton University.

Begdache had previously published research suggesting that mental ...

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) is often used to determine the chemical composition of materials. It was developed in the 1960s and is accepted as a standard method in materials science. Researchers at Linköping University, Sweden, however, have shown that the method is often used erroneously.

"It is, of course, an ideal in research that the methods used are critically examined, but it seems that a couple of generations of researchers have failed to take seriously early signals that the calibration method was deficient. This was the case also for a long time in our own research group. Now, however, we hope that XPS will be used ...

PULLMAN, Wash. - A tiny bee imposter, the syrphid fly, may be a big help to some gardens and farms, new research from Washington State University shows.

An observational study in Western Washington found that out of more than 2,400 pollinator visits to flowers at urban and rural farms about 35% of were made by flies--most of which were the black-and-yellow-striped syrphid flies, also called hover flies. For a few plants, including peas, kale and lilies, flies were the only pollinators observed. Overall, bees were still the most common, accounting for about 61% of floral visits, but the rest were made by other insects and spiders.

"We found that there really were a dramatic number of pollinators visiting flowers that were not bees," said Rae Olsson, a WSU post-doctoral ...

For decades, governments and health authorities have tried to steer people away from "vice" products such as tobacco, soda and alcohol through counter-marketing measures -- things like tax increases, usage restrictions and ad campaigns.

But which ones are the most effective? And what do they mean for big brands such as Marlboro, Coca-Cola, McDonald's and Budweiser?

According to a new study from the UBC Sauder School of Business, they can all help people quit -- but how much they help, and who pays the price, varies significantly.

The researchers also found that tax hikes can disproportionately ...

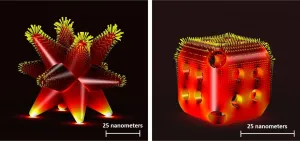

New research is showing that some tiny catalysts being considered for industrial-scaled environmental remediation efforts may be unstable during operation.

Chemists from the University of Waterloo studied the structures of complex catalysts known as "nanoscale electrocatalysts" and found that they are not as stable as scientists once thought. When electricity flows through them during use, the atoms may rearrange. In some cases, the researchers found, electrocatalysts degrade completely.

Understanding why and how this rearrangement and degradation happens is the first step to using these nanoscale electrocatalysts in environmental remediation efforts such as removing atmospheric carbon dioxide ...

Holding onto everyday items as keepsakes when a loved one dies was as commonplace in prehistory as it is today, a new study suggests.

The study from the University of York suggests mundane items like spoons and grinding stones were kept by Iron Age people as an emotional reminder and a 'continuing bond' with the deceased - a practice which is replicated in societies across the globe today.

The research focused on "problematic stuff": everyday items used or owned by a deceased person that relatives might not want to reuse but which they are unable to simply throw away.

At the Scottish hillfort settlement of Broxmouth, dating from 640BC to AD210, everyday items like quernstones, used for grinding grain, and bone spoons found between roundhouse walls could have been placed there by ...

A smartphone-based eye screening and referral system used in the community has been shown to almost triple the number of people with eye problems attending primary care, as well as increasing appropriate uptake of hospital services, compared to the standard approach. The new findings come from research carried out in Kenya, published in The Lancet Digital Health.

The randomised controlled trial included more than 128,000 people in Trans Nzoia County, Kenya, and was carried out by researchers from the International Centre for Eye Health (ICEH) at the London School ...

The initial chemotherapy of aggressive childhood nerve tumors, so-called high-risk neuroblastomas, is crucial for ultimate survival. It has now been shown that the chemotherapy regimen used by the European Neuroblastoma Study Group is equally efficacious but better tolerated than a highly effective regimen from the US. This was the conclusion of an international trial coordinated by St. Anna Children's Cancer Research Institute. The study was published in the prestigious Journal of Clinical Oncology.

For particularly aggressive nerve tumors in children, so-called high-risk neuroblastomas, various ...