Exotic superconductors: The secret that wasn't there

How reproducible are measurements in solid-state physics? New measurements show: An allegedly sensational effect does not exist at all

2021-06-22

(Press-News.org) A single measurement result is not a proof - this has been shown again and again in science. We can only really rely on a research result when it has been measured several times, preferably by different research teams, in slightly different ways. In this way, errors can usually be detected sooner or later.

However, a new study by Prof. Andrej Pustogow from the Institute of Solid State Physics at TU Wien together with other international research teams shows that this can sometimes take quite a long time. The investigation of strontium ruthenate, a material that plays an important role in unconventional superconductivity, has now disproved an experiment that gained fame in the 1990s: it was believed that a novel form of superconductivity had been discovered. As it now turns out, however, the material behaves very similarly to other well-known high-temperature superconductors. Nevertheless, this is an important step forward for research.

Two particles with coupled spin

Superconductivity is one of the great mysteries of solid-state physics: certain materials lose their electrical resistance completely at low temperatures. This effect is still not fully understood. What is certain, however, is that so-called "Cooper pairs" play a central role in superconductivity.

In a normal metal, electric current consists of individual electrons that collide with each other and with the metal atoms. In a superconductor, the electrons move in pairs. "This changes the situation dramatically," explains Andrej Pustogow. "It's similar to the difference between a crowd in a busy shopping street and the seemingly effortless motion of a dancing couple on the dance floor." When electrons are bound in Cooper pairs, they do not lose energy through scattering and move through the material without any disturbance. The crucial question is: Which conditions lead to this formation of Cooper pairs?

"From a quantum physics point of view, the important thing is the spin of these two electrons," says Andrej Pustogow. The spin is the magnetic moment of an electron and can point either 'up' or 'down'. In Cooper pairs, however, a coupling occurs: in a 'singlet' state, the spin of one electron points upwards and that of the other electron points downwards. The magnetic moments cancel each other out and the total spin of the pair is always zero.

However, this rule, which almost all superconductors follow, seemed to be broken by the Cooper pairs in strontium ruthenate (Sr2RuO4). In 1998, results were published that indicated Cooper pairs in which the spins of both electrons point in the same direction (then it is a so-called "spin triplet"). "This would enable completely new applications," explains Andrej Pustogow. "Such triplet Cooper pairs would then no longer have a total spin of zero. This would allow them to be manipulated with magnetic fields and used to transport information without loss, which would be interesting for spintronics and possible quantum computers."

This caused quite a stir, not least because strontium ruthenate was also considered a particularly important material for superconductivity research for other reasons: its crystal structure is identical to that of cuprates, which exhibit high-temperature superconductivity. While the latter are deliberately doped with "impurities" to make superconductivity possible, Sr2RuO4 is already superconducting in its pure form.

New measurement, new result

"Actually, we studied this material for a completely different reason," says Andrej Pustogow. "But in the process, we realised that these old measurements could not be correct." In 2019, the international team was able to show that the supposedly exotic spin effect was just a measurement artefact: the measured temperature did not match the actual temperature of the sample studied; in fact, the sample studied at the time was not superconducting at all. With this realisation in mind, the superconductivity of the material was now re-examined with great precision. The new results clearly show that strontium ruthenate is not a triplet superconductor. Rather, the properties correspond to what is already known from cuprates.

However, Andrej Pustogow does not find this disappointing: "It is a result that brings our understanding of high-temperature superconductivity in these materials another step forward. The finding that strontium ruthenate shows similar behaviour to cuprates means two things: On the one hand, it shows that we are not dealing with an exotic, new phenomenon, and on the other hand it also means that we have a new material at our disposal, in which we can investigate already known phenomena." Ultra-pure strontium ruthenate is better suited for this than previously known materials. It offers a much cleaner test field than cuprates.

In addition, one also learns something about the reliability of old, generally accepted publications: "Actually, one might think that results in solid-state physics can hardly be wrong," says Pustogow. "While in medicine you might have to be satisfied with a few laboratory mice or a sample of a thousand test subjects, we examine billions of billions (about 10 to the power of 19) electrons in a single crystal. This increases the reliability of our results. But that does not mean that every result is completely correct. As everywhere in science, reproducing previous results is indispensable in our field - and so is falsifying them."

INFORMATION:

Contact

Ass. Prof. Dr. Andrej Pustogow

Institute for Solid State Physics

TU Wien

+43 1 58801 13128

pustogow@ifp.tuwien.ac.at

http://www.ifp.tuwien.ac.at/forschung/pustogow-research/home, opens an external URL in a new window

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-22

The spinal cord is an important component of our central nervous system: it connects the brain with the rest of the body and plays a crucial part in coordinating our sensations with our actions. Falls, violence, disease - various forms of trauma can cause irreversible damage to the spinal cord, leading to paralysis, sometimes even death.

Although many vertebrates, including humans, are unable to recover from a spinal cord injury, some animals stand out. For instance, the axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum), a salamander from Mexico, has the remarkable ability to regenerate its spinal cord after an injury. When an axolotl's tail is amputated, neural stem cells residing in the spinal cord are recruited to the injury ...

2021-06-22

Researchers have identified a combination of biological markers in patients with dengue that could predict whether they go on to develop moderate to severe disease, according to a study published today in eLife.

Biomarkers are used to identify the state or risk of a disease in patients. Examples of biomarkers can include naturally occurring molecules or genes in the vascular, inflammatory or other biological pathways. The new findings could aid the development of biomarker panels for clinical use and help improve triage and risk prediction in patients with dengue.

Dengue is the most common mosquito-borne viral disease to affect humans globally. In 2019, the World Health Organization identified dengue as one of the top 10 threats to global health, with transmission occurring ...

2021-06-22

The ancient Maya city of Tikal was a bustling metropolis and home to tens of thousands of people.

The city comprised roads, paved plazas, towering pyramids, temples and palaces and thousands of homes for its residents, all supported by agriculture.

Now researchers at the University of Cincinnati say Tikal's reservoirs -- critical sources of city drinking water -- were lined with trees and wild vegetation that would have provided scenic natural beauty in the heart of the busy city.

UC researchers developed a novel system to analyze ancient plant DNA in the sediment of Tikal's temple and palace reservoirs to identify more than 30 species ...

2021-06-22

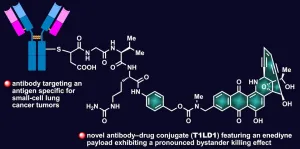

HOUSTON - (June 22, 2021) - How do you kill tumor cells that can't be targeted? Get their more susceptible neighbors to help.

The Rice University lab of synthetic chemist K.C. Nicolaou, in collaboration with AbbVie Inc., has created unique antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) that link a synthetic uncialamycin analogue to antibodies that target cancer cells.

Once they enter the targeted tumor cells, these ADCs exhibit a "significant bystander effect," according to the study. In other words, cancerous neighbor cells that aren't directly attacked by the drugs are also affected.

The study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences presents "an intriguing opportunity ...

2021-06-22

Researchers at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine have developed a blueprint for a protein that plays an important role in the development and regulation of reproductive organs.

The knowledge advances our understanding of the protein anti-Müllerian hormone hormone (AMH), which helps form male reproductive organs and in females regulates follicle development and ovulation in the ovaries, explains Thomas Thompson, PhD, professor in the UC Department of Molecular Genetics, Biochemistry and Microbiology.

Scientists have been looking to regulate AMH because it might play a role in developing a novel contraceptive, aid in treatments for infertility ...

2021-06-22

An enzyme found in fat tissue in the centre of our bones helps control the production of new bone and fat cells, shows a study in mice published today in eLife.

The findings may help scientists better understand how the body maintains fat stores and bone production in response to changing conditions, such as during aging. They may also suggest new approaches to treating conditions that cause bone loss in older adults.

Fat cells, including those found in the bone marrow, are increasingly recognised as an important part of the body that helps regulate body weight, insulin sensitivity and bone mass. Fat tissue ...

2021-06-22

DETROIT - Jessica Damoiseaux, Ph.D., an associate professor with the Institute of Gerontology at Wayne State University, recently published the results of a three-year study of cognitive changes in older adults. The team followed 69 primarily African American females, ages 50 to 85, who complained that their cognitive ability was worsening though clinical assessments showed no impairments. Three magnetic resonance imaging scans (MRIs) at 18-month intervals showed significant changes in functional connectivity in two areas of the brain.

"An older adult's perceived cognitive decline could be an important precursor to dementia," Damoiseaux said. "Brain alterations that underlie the experience of decline could reflect ...

2021-06-22

(Boston)--Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths. Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 80-85 percent cases of lung cancer and when diagnosed early, has a five-year survival rate of 50-80 percent. Black patients have lower overall incidence of NSCLC than white patients, but are more likely to be diagnosed at later stages. They also are less likely to receive surgery for early-stage cancer.

Now a new study from Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) highlights the impact that structural racism and residential segregation has on NSCLC outcomes.

The researchers analyzed patient data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program--a database of Black and white patients diagnosed with NSCLC from 2004-2016 in the 100 ...

2021-06-22

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- What motivated Americans to wear masks and stay socially distanced (or not) at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic? More often than not, it was partisanship, rather than perceived or actual health risk, that drove their behavior, according to a new study co-authored by researchers at Brown University.

By analyzing the results of two online surveys of more than 1,100 adults in total, Mae Fullerton, a Class of 2021 Brown graduate, and Steven Sloman, a professor of cognitive, linguistic and psychological sciences, found that in spring and fall 2020, political partisanship was the strongest predictor of whether someone ...

2021-06-22

An analysis of survey data from more than 280,000 young adults ages 18-35 showed that cannabis (marijuana) use was associated with increased risks of thoughts of suicide (suicidal ideation), suicide plan, and suicide attempt. These associations remained regardless of whether someone was also experiencing depression, and the risks were greater for women than for men. The study published online today in JAMA Network Open and was conducted by researchers at the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health.

"While we cannot establish that cannabis use caused the increased suicidality we observed in this study, these associations warrant further research, especially ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Exotic superconductors: The secret that wasn't there

How reproducible are measurements in solid-state physics? New measurements show: An allegedly sensational effect does not exist at all