Investigators at the Stanford School of Medicine and Saarland University in Germany report that what they saw looks a lot like what's observed in the brains of people who died of neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.

The findings may help explain why many COVID-19 patients report neurological problems. These complaints increase with the severity of infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. And they can persist as an aspect of "long COVID," a long-lasting disorder that sometimes arises following infection. About one-third of individuals hospitalized for COVID-19 report symptoms of fuzzy thinking, forgetfulness, difficulty concentrating and depression, said Tony Wyss-Coray, PhD, professor of neurology and neurological sciences at Stanford.

Yet the researchers couldn't find any signs of SARS-CoV-2 in brain tissue they obtained from eight individuals who died of the disease. Brain samples from 14 people who died of other causes were used as controls for the study.

"The brains of patients who died from severe COVID-19 showed profound molecular markers of inflammation, even though those patients didn't have any reported clinical signs of neurological impairment," said Wyss-Coray, who is the D. H. Chen Professor II.

Scientists disagree about whether SARS-CoV-2 is present in COVID-19 patients' brains. "We used the same tools they've used -- as well as other, more definitive ones -- and really looked hard for the virus's presence," he said. "And we couldn't find it."

A paper describing the study will be published June 21 in Nature. Wyss-Coray shares senior authorship with Andreas Keller, PhD, chair of clinical bioinformatics at Saarland University. The lead authors are Andrew Yang, PhD, a postdoctoral scholar in Wyss-Coray's group, and Fabian Kern, a graduate student in Keller's group.

Blood-brain barrier

The blood-brain barrier, which consists in part of blood-vessel cells that are tightly stitched together and blob-like abutments created by brain cells' projections squishing up against the vessels, has until recently been thought to be exquisitely selective in granting access to cells and molecules produced outside the brain.

But previous work by Wyss-Coray's group and by others has shown that bloodborne factors outside the brain can signal through the blood-brain barrier to ignite inflammatory responses inside the brain. This could explain why, as Wyss-Coray and his colleagues have discovered, factors in young mice's blood can rejuvenate older mice's cognitive performance, whereas blood from old mice can detrimentally affect their younger peers' mental ability.

On hearing reports of enduring neurological symptoms among some COVID-19 patients, Wyss-Coray became interested in how SARS-CoV-2 infection might cause such problems, which resemble those that occur due to aging as well as to various neurodegenerative diseases. Having also seen conflicting reports of the virus's presence in brain tissue in other studies, he wanted to know whether the virus does indeed penetrate the brain.

Brain tissue from COVID-19 patients is hard to find, Wyss-Coray said. Neuropathologists are reluctant to take the steps required to excise it because of potential exposure to SARS-CoV-2 and because regulations often prohibit such procedures to prevent viral transmission. But Keller, who has worked in the Wyss-Coray lab as a visiting professor at Stanford, was able to access COVID-19 brain-tissue samples from autopsies conducted at the hospital that's associated with Saarland University.

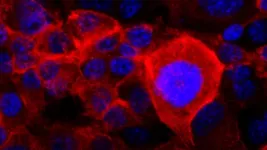

Using an approach called single-cell RNA sequencing, the scientists logged the activation levels of thousands of genes in each of 65,309 individual cells taken from brain-tissue samples from the COVID-19 patients and the controls.

In neurons of the cerebral cortex, signs of distress

Activation levels of hundreds of genes in all major cell types in the brain differed in the COVID-19 patients' brains versus the control group's brains. Many of these genes are associated with inflammatory processes.

There also were signs of distress in neurons in the cerebral cortex, the brain region that plays a key role in decision-making, memory and mathematical reasoning. These neurons, which are mostly of two types -- excitatory and inhibitory -- form complex logic circuits that perform those higher brain functions.

The outermost layers of the cerebral cortex of patients who died of COVID-19 showed molecular changes suggesting suppressed signaling by excitatory neurons, along with heightened signaling by inhibitory neurons, which act like brakes on excitatory neurons. This kind of signaling imbalance has been associated with cognitive deficits and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease.

An additional finding was that peripheral immune cells called T cells, immune cells that prowl for pathogens, were significantly more abundant in brain tissue from dead COVID-19 patients. In healthy brains, these immune cells are few and far between.

"Viral infection appears to trigger inflammatory responses throughout the body that may cause inflammatory signaling across the blood-brain barrier, which in turn could trip off neuroinflammation in the brain," Wyss-Coray said.

"It's likely that many COVID-19 patients, especially those reporting or exhibiting neurological problems or those who are hospitalized, have these neuroinflammatory markers we saw in the people we looked at who had died from the disease," he added. It may be possible to find out by analyzing these patients' cerebrospinal fluid, whose contents to some extent mirror those of the living brain.

"Our findings may help explain the brain fog, fatigue, and other neurological and psychiatric symptoms of long COVID," he said.

INFORMATION:

Wyss-Coray is co-director of the Paul F. Glenn Center for Biology of Aging Research at Stanford, a member of Stanford Bio-X, Stanford's Maternal and Child Health Research Institute, and Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute at Stanford, and a faculty fellow of ChEM-H.

Other Stanford co-authors of the study are postdoctoral scholars Patricia Losada, PhD, Nicholas Schaum, PhD, Ryan Vest, PhD, Nannan Lu, PhD, and Oliver Hahn, PhD; basic life research scientist Daniela Berdnik, PhD; life science research professionals Maayan Agam and Kruti Calcuttawala; former life science research associate Davis Lee; former visiting student researcher Christina Maat; life science research professional Divya Channappa; David Gate, PhD, instructor of neurology and neurological sciences; M. Windy McNerney, PhD, clinical assistant professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences; and Imma Cobos, MD, PhD, assistant professor of pathology.

In addition to Keller and Kern, other researchers at Saarland University also contributed to the study.

The work was funded by the Nomis Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (grants T32-AG0047126, 1RF1AG059694 and P30AG066515), Nan Fung Life Sciences, the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute and the Stanford Alzheimer's Disease Research Center.

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://med.stanford.edu/school.html. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Health Care and Stanford Children's Health. For information about all three, please visit http://med.stanford.edu.