(Press-News.org) Almost all cells in our body contain a nucleus: a somewhat spherical structure that is separated from the rest of the cell by a membrane. Each nucleus contains all the genetic information of the human being. So it serves as a kind of library - but one with strict requirements: If the cell needs the building instructions for a protein, it won't simply borrow the original information. Instead, a transcript of it is made in the nucleus.

The machinery required for this is very complex, not least because the transcripts are not simple copies. In addition to essential information, genes also contain numerous passages of meaningless "garbage". They are removed when the transcript is made. Biologists call this editorial revision "splicing".

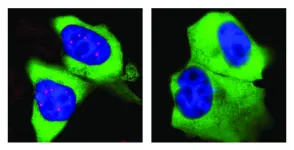

"An important role in splicing is played by the SMN complex, a 'molecular machine' consisting of nine different proteins," explains Prof. Dr. Oliver Gruss from the Institute of Genetics at the University of Bonn, who is also a member of the university's transdisciplinary research area "Life and Health". "Interestingly, these machines are not evenly distributed in the nucleus. Instead, they accumulate at specific sites called Cajal bodies." However, there are no transport mechanisms in the cell nucleus that bring the SMN complexes to Cajal bodies. Instead, the SMN proteins themselves have certain properties that are responsible for their aggregation. Which ones these are, was unclear until now.

SMN complexes carry an unusually large number of phosphate groups

SMN complexes have a prominent feature: They carry an unusually large number of phosphate groups, which are small molecular residues with a phosphorus atom in the center. "We suspected that this phosphorylation promotes their mass clustering into Cajal bodies," explains Dr. Maximilian Schilling from the research group around Oliver Gruss.

Phosphate groups are not part of the actual blueprint of a protein - they are added later and can also be removed again. This is often how the cell regulates the activity of the respective protein. The phosphate group is attached in this process by certain enzymes, the kinases. "We have now inhibited each of the hundreds of human kinases individually and looked at how that affects the formation of Cajal bodies," Schilling says.

In this way, they encountered a network of kinases, which, when inhibited, caused the Cajal bodies to largely disappear. Further analyses showed that in the absence of these kinases, phosphorylation of SMN complexes at specific sites decreased sharply. This then causes the flash mobs in the nucleus to cease - the Cajal bodies disintegrate. The finding is particularly interesting because the kinases identified not only regulate splicing, but also the translation of the gene transcripts edited in this way into proteins. These are therefore enzymes that are crucial for various steps in this vital process.

Mutation causes severe disease

The SMN complex is known to human geneticists not only for its role in splicing: Individual mutations in its blueprint result in a serious disease, spinal muscular atrophy, in those affected. One in about 6,000 newborns is born with this genetic defect. Treatment is extremely expensive; the cost per patient runs into millions. "Some of the gene defects that cause spinal muscular atrophy are near the phosphorylation sites of the SMN complex," explains Gruss. "Affected individuals may therefore have impaired attachment of phosphate groups to these sites, and consequently also impaired formation of Cajal bodies. We suspect that this causes splicing to be impaired, which subsequently results in the disease symptoms."

The kinases identified may therefore also be suitable as a starting point for new therapies. Preliminary results from mouse model cells for human spinal muscular atrophy show that agents that increase kinase activity also improve Cajal body formation. "It is completely unclear whether these agents also ameliorate pathological changes in a complex organism," cautions Gruss against inflated expectations. "That new treatment options will eventually emerge from this is therefore still speculation at this stage."

INFORMATION:

Participating institutions:

The universities of Bonn, Würzburg and Heidelberg were involved in the study with the help of Evotec SE at the Martinsried.

Persons suffering from the autoimmune disease multiple sclerosis can develop various neurological symptoms caused by damage to the nervous system. Especially in early stages, these may include sensory dysfunction such as numbness or visual disturbances. In most patients, MS starts with recurring episodes of neurological disability, called relapses or demyelinating events. These clinical events are followed by a partial or complete remission. Especially in the beginning, the symptoms vary widely, so that it is often difficult even for experienced doctors to interpret them correctly to arrive at a diagnosis of MS.

Above-average numbers of medical appointments

It has been evident for some ...

The most comprehensive molecular study to date of the brains of people who died of COVID-19 turned up unmistakable signs of inflammation and impaired brain circuits.

Investigators at the Stanford School of Medicine and Saarland University in Germany report that what they saw looks a lot like what's observed in the brains of people who died of neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.

The findings may help explain why many COVID-19 patients report neurological problems. These complaints increase with the severity of infection with SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. And they can persist as an aspect of "long COVID," a long-lasting disorder that sometimes ...

If only it were as simple as finding more grassland for an antelope.

The story of efforts to conserve the endangered oribi in South Africa represent a diaspora of issues as varied as the people who live there. On its surface, like many threatened species, you have conflict between a need for habitat and private landownership.

But dig a little deeper and you'll uncover a seedy underbelly of political corruption, gambling, struggles over land, and racial tensions. No matter how much success is made through more traditional conservation efforts, says a new study by a University of Georgia researcher, the species ...

Rutgers scientists have used a diagnostic technique for the first time in the opioid addiction field that they believe has the potential to determine which opioid-addicted patients are more likely to relapse.

Using an algorithm that looks for patterns in brain structure and functional connectivity, researchers were able to distinguish prescription opioid users from healthy participants. If treatment is successful, their brains will resemble the brain of someone not addicted to opioids.

"People can say one thing, but brain patterns do not lie," said Suchismita Ray, lead researcher and an associate professor in the Department of Health Informatics at Rutgers School of Health Professions. "The brain patterns that ...

Cancer cells can become resistant to treatments through adaptation, making them notoriously tricky to defeat and highly lethal. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Cancer Center Director David Tuveson and his team investigated the basis of "adaptive resistance" common to pancreatic cancer. They discovered one of the backups to which these cells switch when confronted with cancer-killing drugs.

KRAS is a gene that drives cell division. Most pancreatic cancers have a mutation in the KRAS protein, causing uncontrolled growth. But, drugs that shut off mutant KRAS do not stop the proliferation. ...

Lifestyle changes for demand-side climate change mitigation is gaining more and more importance and attention. A new IIASA-led study set out to understand the full potential of behavior change and what drives such changes in people's choices across the world using data from almost two billion Facebook profiles.

Modern consumption patterns, and especially livestock production in the agricultural sector to sustain the world's growing appetite for animal products, are contributing to and speeding the advance of interconnected issues like climate change, air pollution, and biodiversity ...

Imagine flexible surgical instruments that can twist and turn in all directions like miniature octopus arms, or how about large and powerful robot tentacles that can work closely and safely with human workers on production lines. A new generation of robotic tools are beginning to be realized thanks to a combination of strong 'muscles' and sensitive 'nerves' created from smart polymeric materials. A research team led by the smart materials experts Professor Stefan Seelecke and Junior Professor Gianluca Rizzello at Saarland University is exploring fundamental aspects of this exciting field of soft robotics.

In the factory of ...

As well as bright colours and subtle scents, flowers possess many invisible ways of attracting their pollinators, and a new study shows that bumblebees may use the humidity of a flower to tell them about the presence of nectar, according to scientists at the Universities of Bristol and Exeter.

This new research has shown that bumblebees are able to accurately detect and choose between flowers that have different levels of humidity next to the surface of the flower.

The study, published this week in the Journal of Experimental Biology, showed that bees could be trained to differentiate between two types of artificial flower with different levels of humidity, if only one of the types of flower provided the bee with a reward of sugar water.

To make sure that the artificial flowers ...

Augmented reality (AR) is poised to revolutionise the way people complete essential everyday tasks, yet older adults - who have much to gain from the technology - will be excluded from using it unless more thought goes into designing software that makes sense to them.

The danger of older adults falling through the gaps has been highlighted by research carried out by scientists at the University of Bath in the UK in collaboration with designers from the Bath-based charity Designability. A paper describing their work has received an honourable mention at this year's Human Computer Interaction Conference (CHI2021) - the world's largest conference of its kind.

The ...

According to a recent study, open learning spaces are not directly associated with the physical activity of students in grades 3 and 5, even though more breaks from sedentary time were observed in open learning spaces compared to conventional classrooms.

The findings are based on the CHIPASE study, carried out at the Faculty of Sport and Health Science of the University of Jyväskylä. The results were published in Frontiers of Sports and Active Life.

After the reform of the national core curriculum for basic education in Finland, issued in 2016, most of the new or renovated comprehensive schools in Finland began to incorporate ...