Sound-induced electric fields control the tiniest particles

Acoustoelectronic tweezers gently manipulate biological nanoparticles just a few nanometers wide

2021-06-23

(Press-News.org) Engineers at Duke University have devised a system for manipulating particles approaching the miniscule 2.5 nanometer diameter of DNA using sound-induced electric fields. Dubbed "acoustoelectronic nanotweezers," the approach provides a label-free, dynamically controllable method of moving and trapping nanoparticles over a large area. The technology holds promise for applications in the fields ranging from condensed matter physics to biomedicine.

The research appears online on June 22 in Nature Communications.

Precisely controlling nanoparticles is a crucial ability for many emerging technologies. For example, separating exosomes and other tiny biological molecules from blood could lead to new types of diagnostic tests for the early detection of tumors and neurodegenerative diseases. Placing engineered nanoparticles in a specific pattern before fixing them in place can help create new types of materials with highly tunable properties.

For more than a decade, Tony Jun Huang, the William Bevan Distinguished Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science at Duke, has pursued acoustic tweezer systems that use sound waves to manipulate particles. However, it becomes difficult to push things around with sound when their profile drops below that of some of the smallest viruses.

"Although we're still fundamentally using sound, our acoustoelectronic nanotweezers use a very different mechanism than these previous technologies," said Joseph Rufo, a graduate student working in Huang's laboratory. "Now we're not only exploiting acoustic waves, but electric fields with the properties of acoustic waves."

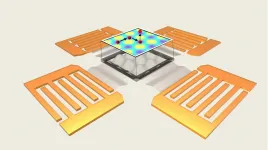

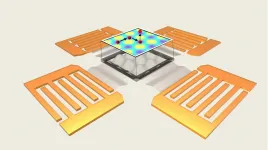

Instead of using sound waves to directly move the nanoparticles, Huang, Rufo and Peiran Zhang, a postdoc in Huang's laboratory, use sound waves to create electric fields that provide the push. The new acoustoelectronic tweezer approach works by placing a piezoelectric substrate--a thin material that creates electricity in response to mechanical stress--beneath a small chamber filled with liquid. Four transducers are aligned on the chamber's sides, which send sound waves into the piezoelectric substrate.

These sound waves bounce around and interact with one another to create a stable pattern. And because the sound waves are creating stresses within the piezoelectric substrate, they also create electrical fields. These couple with the acoustic waves in a way that creates electric field patterns within the chamber above.

"The vibrations of the sound waves also make the electric field dynamically alternate between positive and negative charges," said Zhang. "This alternating electric field polarizes the nanoparticles in liquid, which serves as a handle to manipulate them."

The result is a mechanism that mixes some of the strengths of other nanoparticle manipulators. Because the acoustoelectronic nanotweezers induce an electromagnetic response in the nanomaterials, the nanoparticles do not need to be conductive on their own or tagged with any sort of modifier. And because the patterns are created with sound waves, their positions and properties can be quickly and easily modified to create a variety of options.

In the prototype, the researchers show nanoparticles placed into striped and checkerboard patterns. They even push individual particles around in an arbitrary manner dynamically, spelling out letters such as D, U, K and E. The researchers then demonstrate that these aligned nano-patterns can be transferred onto dry films using delicate nanoparticles such as carbon nanotubes, 3.5-nanometer proteins and 1.4-nanometer dextran often used in biomedical research. And they show that all of this can be accomplished on a working area that is tens to hundreds of times larger than current state-of-the-art nanotweezing technologies.

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM132603, R01GM135486, UG3TR002978, R33CA223908, R01GM127714), the United States Army Medical Research Acquisition Activity (W81XWH-18-1-0242), and the National Science Foundation (ECCS-1807601).

CITATION: "Acoustoelectronic Nanotweezers Enable Dynamic, Large-Scale Control of Nanomaterials," Peiran Zhang, Joseph Rufo, Chuyi Chen, Jianping Xia, Zhenhua Tian, Liying Zhang, Nanjing Hao, Zhanwei Zhong, Yuyang Gu, Krishnendu Chakrabarty, and Tony Jun Huang. Nature Communications, June 22, 2021. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-24101-z

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-23

Until recently, data on criminal victimization did not include information on the status--immigrant or citizen--of respondents. In a recent study, researchers used new data that include respondents' status to explore the association between citizenship status and risk of victimization. They found that for many, a person's foreign-born status, but not their acquired U.S. citizenship, protects against criminal victimization.

The study, by researchers at the University of Maryland (UMD) at College Park and the Pennsylvania State University (PSU), is forthcoming in Criminology, a publication of the American Society of Criminology.

"Understanding how patterns of victimization vary ...

2021-06-23

New Orleans, LA - An analysis conducted by a group of investigators including Tamara Bradford, MD, Associate Professor of Pediatrics at LSU Health New Orleans School of Medicine, found that children and adolescents with Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) initially treated with intravenous immune globulin (IVIG) plus glucocorticoids had a lower risk of new or persistent cardiovascular dysfunction than IVIG alone. The research was part of the Overcoming COVID-19 Study, a nationwide collaboration of physicians at pediatric hospitals and the Centers for Disease ...

2021-06-23

HOUSTON - (June 22, 2021) - We can't detect them yet, but radio signals from distant solar systems could provide valuable information about the characteristics of their planets.

A paper by Rice University scientists describes a way to better determine which exoplanets are most likely to produce detectable signals based on magnetosphere activity on exoplanets' previously discounted nightsides.

The study by Rice alumnus Anthony Sciola, who earned his Ph.D. this spring and was mentored by co-author and space plasma physicist Frank Toffoletto, shows that while radio emissions from the daysides of exoplanets appear to max out during high solar activity, those that emerge from the nightside are likely to add significantly to the signal.

This interests the exoplanet ...

2021-06-23

New research examined the effect of different parenting styles during adolescence on crime among African American men. The study found that parenting styles characterized by little behavioral control placed youth at significant risk for adult crime, even though some of those styles included high levels of nurturance. In contrast, youth whose parents monitored them, were consistent in their parenting, and had high levels of behavioral control were at lowest risk for adult crime.

The study, by researchers at the University of Georgia and Mississippi State University, is forthcoming in Criminology, a publication of the American Society of Criminology.

"We examined parenting styles rather than parenting ...

2021-06-23

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. - Sunday church service in Amish country is more than just belting out hymns, reading Bible passages and returning home an hour later to catch a football game or nap.

It's an all-day affair: A host family welcomes church members - between 20 to 40 families - into their home to worship and have fellowship with one another from morning to night. Church is a biweekly activity; each gathering takes place in a member's home and is a key ritual in the Amish community which values in-person communication.

New research from West Virginia University sociologists suggests this face-to-face interaction, coupled with a distrust ...

2021-06-23

A new study by Penn State researchers, who looked at emergency room admissions across the U.S. over a recent five-year period in a novel way, suggests that the agriculture industry is even more dangerous than previously believed.

The research revealed that from Jan. 1, 2015, to Dec. 31, 2019, more than 60,000 people were treated in emergency departments for nonfatal, agricultural-related injuries. Significantly, nearly a third of those injured were youths, according to study author Judd Michael, Nationwide Insurance Professor of Agricultural Safety and Health and professor of agricultural and biological engineering, College of Agricultural Sciences.

"This study revealed the true magnitude of the agricultural-related injury problem," he said. "We were slightly ...

2021-06-23

Interstate highway systems and networks of dense urban roads typically receive top billing on maps, in infrastructure legislation and in travelers' daily commuting routes. However, more than 80% of all US roads are considered low-volume roads - defined as those that carry fewer than 1000 vehicles per day. According to a new report published by the Ecological Society of America, "The Ecology of Rural Roads: Effects, Management and Research," this less-traveled road network can have an outsized impact on surrounding ecosystems, altering the local hydrology, affecting wildlife populations and shuttling ...

2021-06-23

WASHINGTON--More than half of the structures in the contiguous United States are exposed to potentially devastating natural hazards--such as floods, tornadoes and wildfires--according to a new study in the AGU journal Earth's Future, which publishes interdisciplinary research on the past, present and future of our planet and its inhabitants.

Increasing temperatures and environmental changes contribute to this trend, and the research also shines the light on another culprit: the way humans develop open land, towns and cities.

"We know that climate ...

2021-06-22

Large thunderstorms in the Southern Great Plains of the U.S. are some of the strongest on Earth. In recent years, these storms have increased in frequency and intensity, and new research shows that these shifts are linked to climate variability.

Co-authored by Christopher Maupin, Courtney Schumacher and Brendan Roark, all scientists in Texas A&M University's College of Geosciences, along with other researchers, the findings were recently published in END ...

2021-06-22

Managing type 2 diabetes typically involves losing weight, exercise and medication, but new research by Dr. Makoto Fukuda and colleagues at Baylor College of Medicine and other institutions suggests that there may be other ways to control the condition through the brain. The researchers have discovered a mechanism in a small area of the brain that regulates whole-body glucose balance without affecting body weight, which suggests the possibility that modulating the mechanism might help keep blood sugar levels in a healthy range.

"A growing body of evidence strongly suggests that the brain is a promising yet unrealized ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Sound-induced electric fields control the tiniest particles

Acoustoelectronic tweezers gently manipulate biological nanoparticles just a few nanometers wide