(Press-News.org) CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Researchers report that they have developed a method to combine three brain-imaging techniques to more precisely capture the timing and location of brain responses to a stimulus. Their study is the first to combine the three widely used technologies for simultaneous imaging of brain activity. The work is reported in the journal Human Brain Mapping.

The new "trimodal" approach combines functional MRI, electroencephalography and a third technique, called EROS, that tracks the activity of neurons near the surface of the brain using near-infrared light.

"We know that fMRI is very good at telling us where in the brain things are happening, but the signal is quite slow," said postdoctoral researcher Matthew Moore, the first author of the study, which was conducted at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign's Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology. "And when we measure electrical activity through EEG, it is very good at telling us when things happen in the brain - but it's less precise about where."

The third method, called event-related optical signal, provides a measure of spatial information that is similar to fMRI but, like EEG, can more accurately assess the timing of brain responses. This helps researchers fill in the blanks left by the other two technologies, Moore said. The result is a clearer picture of how different parts of the brain are activated and communicate with one another when an individual engages in a cognitive task and is distracted - in this case, by emotionally challenging information.

Functional MRI captures a signal from the flow of oxygenated blood in the brain when a person sees or responds to a stimulus. This signal is very useful for determining which brain structures are being activated, Moore said.

"Changes in blood oxygenation levels occur over a period of seconds, but the brain actually responds within hundreds of milliseconds," he said. This lag between brain activity and oxygenation signals means fMRI is unable to detect changes occurring faster than seconds.

"On the other hand, EEG is very good at telling us when things happen," Moore said. "But we're collecting from sensors placed on the scalp, and we're getting a summation of activity, so really, we're blurring across centimeters of the scalp."

The third technique, EROS, was developed by two co-authors of the new report, U. of I. psychology professors Monica Fabiani and Gabriele Gratton. This method shines near-infrared light into the brain and measures changes in how the light scatters, a reflection of neural activity. EROS provides precise information about where and when the brain responds, but it can only penetrate a few centimeters below the scalp, so it cannot detect events occurring deeper in the brain, as fMRI can, the researchers said.

Combining the three techniques was no easy task. There is limited space available on the scalp for various electrodes and sensors, and the EEG and EROS equipment had to fit within an fMRI coil and could not contain any magnetic metals, the researchers said. Over a period of years, the researchers found a way to include EROS patches that could share space with EEG electrodes on the scalp. They tested different combinations of the three techniques to determine how to intertwine them and how to interpret the information coming through the different channels.

To study how the brain behaves when an individual tries to focus on a task but is distracted by emotional information, the researchers gave study participants a goal of quickly picking out circles from a series of squares and other images that had either emotionally neutral or negative content.

The imaging results revealed that various brain regions responded rapidly to the stimuli. The signals cycled back and forth between locations over parts of the prefrontal and parietal cortices, brain areas that work together to maintain attention and process distractions. This switching occurred on a time scale of hundreds of milliseconds, the researchers found.

The ability to switch attention from a distraction and get back on task is highly relevant to normal cognitive function, said study leader Florin Dolcos, a professor of psychology at Illinois who studies emotional regulation and cognition.

"Sometimes people with depression or anxiety are not able to switch away from emotional distractions and focus," he said. "Better imaging studies will make it easier to test individuals who have been trained in specific emotion-regulation strategies to see if those strategies are working to improve their cognition. And now we can image this with precision in real time, at the mind's speed," he said.

The trimodal approach will provide better answers to other questions about how the brain operates, the researchers said.

"In previous work, these three technologies were applied on the same individuals at different times," Gratton said. "But we gain a lot from measuring these things together."

"This new approach could have a profound effect on neuroscience theory in general, on human neuroscience," Fabiani said. "Because now we don't have to guess about how these different signals align."

INFORMATION:

The study team also included researchers from the University of Michigan, Northeastern University, the University of Alberta in Canada, the University of Birmingham in the U.K., the National Institute on Aging, and the Neuroscience Program and department of bioengineering at the U. of I.

Numerous U. of I. funders supported this research, including the Campus Research Board, the psychology department and the Beckman Institute.

Editor's notes:

To reach Matthew Moore, email mmoore16@illinois.edu.

To reach Monica Fabiani, email mfabiani@illinois.edu.

To reach Gabriele Gratton, email grattong@illinois.edu.

To reach Florin Dolcos, email fdolcos@illinois.edu.

The paper "Proof-of-concept evidence for trimodal simultaneous investigation of human brain function" is available to members of the media from the U. of I. News Bureau.

A potent greenhouse gas, methane is released by many sources, both human and natural. Large cities emit significant amounts of methane, but in many cases the exact emission sources are unknown. Now, researchers reporting in ACS' Environmental Science & Technology have conducted mobile measurements of methane and its sources throughout Paris. Their findings suggest that the natural gas distribution network, the sewage system and furnaces of buildings are ideal targets for methane reduction efforts.

In cities, major sources of atmospheric methane include heating systems, landfills, wastewater ...

Rare-earth elements are in many everyday products, such as smart phones, LED lights and batteries. However, only a few locations have large enough deposits worth mining, resulting in global supply chain tensions. So, there's a push toward recycling them from non-traditional sources, such as waste from burning coal -- fly ash. Now, researchers in ACS' Environmental Science & Technology report a simple method for recovering these elements from coal fly ash using an ionic liquid.

While rare-earth elements aren't as scarce as their name implies, major reserves are either in politically ...

A new United Nations report calls for an urgent change in the way the world's oceans are managed.

The report from the International Resource Panel, hosted by the UN Environment Programme, raises concerns that if changes are not made quickly, the consequences will be dire.

The Governing Coastal Resources Report was launched today at an event addressed by Ambassador Peter Thomson, UN Secretary-General's Special Envoy for the Ocean. It outlines the effect land-based human activities have on the marine environment.

Put into context - 80 per cent of marine and coastal pollution originates on land, but there are very few, if any, truly effective governance mechanisms that manage land-ocean ...

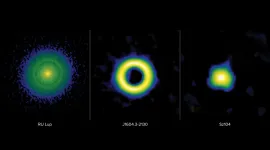

Using data for more than 500 young stars observed with the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA), scientists have uncovered a direct link between protoplanetary disk structures--the planet-forming disks that surround stars--and planet demographics. The survey proves that higher mass stars are more likely to be surrounded by disks with "gaps" in them and that these gaps directly correlate to the high occurrence of observed giant exoplanets around such stars. These results provide scientists with a window back through time, allowing them to predict what exoplanetary ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio - Americans consistently believe that poor African Americans are more likely to move up the economic ladder than they actually are, a new study shows.

People also overestimate how likely poor white people are to get ahead economically, but to a much lesser extent than they do for Black people.

"It's no surprise that most people in our society believe in the American Dream of working hard and succeeding economically," said Jesse Walker, co-author of the study and assistant professor of marketing at The Ohio State University's Fisher College of Business.

"But many people don't know how much harder it is for African Americans to achieve ...

As people go about their daily activities, complex fluctuations in their movement occur without conscious thought. These fluctuations -- known as fractal motor activity regulation (FMAR) -- and their changes are not readily detectable to the naked eye, but FMAR patterns can be recorded using a wristwatch-like device known as an actigraph. A new study, led by investigators at Brigham and Women's Hospital, the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Washington University at St. Louis, analyzed FMAR patterns in cognitively healthy adults who were also tested for established biomarkers of preclinical Alzheimer's disease (AD) pathology. The team found that FMAR was associated with preclinical AD pathology in women, suggesting that FMAR may be a new biomarker for AD before cognitive symptoms ...

BOSTON - Research has previously linked inflammation to Alzheimer's disease (AD), yet scientists from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the Harvard Aging Brain Study (HABS) have made a surprising discovery about that relationship. In a new study published in Alzheimer's & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association, they report that elevated levels of two chemical mediators of inflammation, known as cytokines, are associated with slower cognitive decline in aging adults.

"These are totally unexpected results," says the study's co-senior author, Rudolph Tanzi, PhD, vice chair of Neurology and co-director ...

DALLAS, June 23, 2021 —Can starchy snacks harm heart health? New research published today in the Journal of the American Heart Association, an open access journal of the American Heart Association, found eating starchy snacks high in white potato or other starches after any meal was associated at least a 50% increased risk of mortality and a 44-57% increased risk of CVD-related death. Conversely, eating fruits, vegetables or dairy at specific meals is associated with a reduced risk of death from cardiovascular disease, cancer or any cause.

“People are increasingly ...

A fair society has evolved in banded mongooses because parents don't know which pups are their own, new research shows.

Mothers in banded mongoose groups all give birth on the same night, creating a "veil of ignorance" over parentage in their communal crèche of pups.

In the new study, led by the universities of Exeter and Roehampton, half of the pregnant mothers in wild mongoose groups were regularly given extra food, leading to increased inequality in the birth weight of pups.

But after giving birth, well-fed mothers gave extra care to the ...

Results of the MOSAiC expedition show: the expected recovery of the ozone layer may fail to happen anytime soon, if global warming is not slowed down

In spring 2020, the MOSAiC expedition documented an unparalleled loss of ozone in the Arctic stratosphere. As an evaluation of meteorological data and model-based simulations by the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) now indicates, ozone depletion in the Arctic polar vortex could intensify by the end of the century unless global greenhouse gases are rapidly and systematically reduced. In the future, this could also mean more UV radiation exposure in Europe, North America and Asia when parts ...