(Press-News.org) In many situations, heart muscle cells do not respond to external stresses in the same ways that skeletal muscle cells do. But under some conditions, heart and skeletal muscles can both waste away at fatally rapid rates, according to a new study led by experts at Cincinnati Children's.

The new findings, based on studies of mouse models, represent an important milestone in a long effort to prevent or even reverse cardiac atrophy, which can lead to fatal heart failure when the body loses large amounts of weight or experiences extended periods of weightlessness in space. Detailed findings were published online June 24, 2021, in Nature Communications.

"NASA is very interested in cardiac atrophy," says Jeffery Molkentin, PhD, Co-Director of the Heart Institute at Cincinnati Children's. "It might be the single biggest issue for long-period space flights and astronaut health, especially when re-entering a higher-gravity situation, whether that's arriving at Mars or returning to Earth."

Astronauts and cosmonauts have been exercising in orbit to minimize loss of muscle mass ever since doctors observed years ago that returning spacefarers have often been barely able to walk upon returning to Earth. Along the way, clinicians also have observed increased risk of heart trouble during the recovery period.

The new findings from Molkentin and colleagues help explain why the heart also is affected by muscle-wasting conditions, which in turn suggests potential new ways to prevent or treat the problem.

A three-pronged attack on heart cells

The research team studied mouse models in several ways to trace the withering of heart cells to a three-step molecular process.

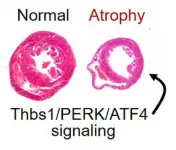

Like skeletal muscle, the heart can either grow larger or smaller depending on workload. The new research identifies a process whereby the gene thrombospondin-1 can result in a dramatic loss of heart mass.

The overexpression of thrombospondin-1 in the hearts of mice lead to rapid and lethal loss of heart mass, called atrophy, by directly activating the signaling protein called PERK. Excessive PERK activity, in turn, triggers a response from the transcription factor ATF4, which together directly program the atrophy of heart muscle cells.

The longer these genes are active, the more severe the atrophy becomes. Eliminating or reducing the activity of these genes would block or reduce the atrophy response, which could be an attractive new strategy for addressing loss of heart muscle during extended periods of space travel.

"Our findings describe a new pathway of muscle mass loss," Molkentin says. "More research is needed to develop methods or drugs that can interrupt this signaling pathway through these genes to stop cardiac atrophy once detected."

Next steps

Researchers still need to confirm that the process observed in mice also occurs in people. More work also is needed to determine whether drugs exist (or need to be developed) that can safely manage the molecular activity the research team has identified.

In humans, even though we lack the ability to replace lost heart muscle tissue, it should be possible to rehabilitate weakened or atrophied heart muscle cells back to their original state.

INFORMATION:

About this study

In addition to Molkentin, Cincinnati Children's researchers contributing to this study include co-first authors Davy Vanhoutte, PhD, and Tobias Schips, PhD, (now at Janssen Pharmaceuticals); Alexander Vo, BS, Kelly Grimes, PhD, Tanya Baldwin, PhD, Matthew Brody PhD, (now at the University of Michigan), Federica Accornero, PhD, (now at the Ohio State University), and Michelle Sargent, BS.

Funding sources for this study include the National Institutes of Health to Molkentin (2R01HL105924) and a grant from the German research foundation Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to Schips (SCHI 1290/1-1).

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO

TORONTO, ON - A new study from researchers at the University of Toronto found that 63% of Canadians with migraine headaches are able to flourish, despite the painful condition.

"This research provides a very hopeful message for individuals struggling with migraines, their families and health professionals," says lead author Esme Fuller-Thomson, who spent the last decade publishing on negative mental health outcomes associated with migraines, including suicide attempts, anxiety disorders and depression. "The findings of our study have contributed to a major paradigm shift for me. There are important lessons to be learned from those who are flourishing."

A migraine headache, which afflicts ...

A recent study finds states that exhibit higher levels of systemic racism also have pronounced racial disparities regarding access to health care. In short, the more racist a state was, the better access white people had - and the worse access Black people had.

"This study highlights the extent to which health care inequities are intertwined with other social inequities, such as employment and education," says Vanessa Volpe, corresponding author of the study and an assistant professor of psychology at North Carolina State University. "This helps explain why health inequities are so intractable. Tackling health care inequities will require us to address broader social systems that significantly benefit white people ...

"Red flag" gun laws--which allow law enforcement to temporarily remove firearms from a person at risk of harming themselves or others--are gaining attention at the state and federal levels, but are under scrutiny by legislators who deem them unconstitutional. A new analysis by legal scholars at NYU School of Global Public Health describes the state-by-state landscape for red flag legislation and how it may be an effective tool to reduce gun violence, while simultaneously protecting individuals' constitutional rights.

Gun violence is a significant public health problem in the U.S., with more than 38,000 people killed by firearms each year. Following several mass shootings this spring, President Biden urged ...

WHO Frank A. J. L. Scheer, PhD, MSc, Neuroscientist and Marta Garaulet, PhD, Visiting Scientist, both of the Division of Sleep and Circadian Disorders, Departments of Medicine and Neurology, Brigham and Women's Hospital. Drs. Scheer and Garaulet are co-corresponding authors of a new paper published in The FASEB Journal.

WHAT Eating milk chocolate every day may sound like a recipe for weight gain, but a new study of postmenopausal women has found that eating a concentrated amount of chocolate during a narrow window of time in the morning may help the body burn fat and decrease blood sugar levels.

To find out about the effects of eating milk chocolate at different times of day, researchers from the Brigham collaborated ...

Philadelphia, June 24, 2021 - Women with depression and other mood disorders are generally advised to continue taking antidepressant medications during pregnancy. The drugs are widely considered safe, but the effect of these medications on the unborn fetus has remained a topic of some concern. Now, researchers have found that maternal psychiatric conditions - but not the use of serotonin-selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) - increased the risk for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and developmental delay (DD) in offspring.

The study appears in Biological Psychiatry, published by Elsevier.

Previous studies had found links between SSRI use and ASD in offspring, and ASD is associated with disrupted serotonergic pathways. But the question of whether ...

With age, a diet lacking in the essential amino acid tryptophan -- which has a key role in our mood, energy level and immune response -- makes the gut microbiome less protective and increases inflammation body-wide, investigators report.

In a normally reciprocal relationship that appears to go awry with age, sufficient tryptophan, which we consume in foods like milk, turkey, chicken and oats, helps keep our microbiota healthy.

A healthy microbiota in turn helps ensure that tryptophan mainly results in good things for us like producing the neurotransmitter serotonin, which reduces depression risk, and melatonin, which ...

Working in the highly charged environment of COVID-19 has had a huge impact on the mental health of nurses, according to a new survey by researchers at the University of British Columbia and the Institute for Work & Health in Toronto.

The findings, described recently in the Annals of Epidemiology, is the first to compare Canadian nurses' mental health prior to and during the pandemic.

"Whether they worked in acute care settings, in community care or in long-term care homes, nurses experienced high rates of depression and anxiety as the pandemic accelerated," says lead researcher Dr. Farinaz Havaei, a professor of nursing at UBC who studies health systems and workplace psychological health and safety.

Prior to the pandemic, two out of 10 nurses reported that they ...

TAMPA, Fla. (June 24, 2021) -- A newly published study by the END ...

Researchers are calling for changes to working culture and conditions for junior doctors in the UK after their new research has highlighted a lack of access to clinical and emotional support.

The call comes as a University of Birmingham-led team of researchers, including experts from Keele University, University College London, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and the Universities of Leeds and Manchester, carried out a qualitative study using in-depth interviews with 21 NHS junior doctors.

All participants, 16 of whom were women ...

**Note this is a special early release from the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID 2021). Please credit the conference if you use this story**

New research being presented at the European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID) held online this year (9-12 July), suggests that one in 10 veterinary workers in the Netherlands carries strains of extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing bacteria compared to around one in 20 of the general Dutch population.

This higher prevalence could not be explained by known risk factors such as antibiotic use or recent travel, and it seems highly likely that occupational contact with animals in the animal healthcare setting may result in shedding and transmission ...