(Press-News.org) Images of dinosaurs as cold-blooded creatures needing tropical temperatures could be a relic of the past.

University of Alaska Fairbanks and Florida State University scientists have found that nearly all types of Arctic dinosaurs, from small bird-like animals to giant tyrannosaurs, reproduced in the region and likely remained there year-round.

Their findings are detailed in a new paper published in the journal Current Biology.

"It wasn't long ago that people were pretty shocked to find out that dinosaurs lived up in the Arctic 70 million years ago," said Pat Druckenmiller, the paper's lead author and director of the University of Alaska Museum of the North. "We now have unequivocal evidence they were nesting up there as well. This is the first time that anyone has ever demonstrated that dinosaurs could reproduce at these high latitudes."

The findings counter previous hypotheses that the animals migrated to lower latitudes for the winter and laid their eggs in those warmer regions. It's also compelling evidence that they were warm-blooded.

For more than a decade, Druckenmiller and Gregory Erickson, a Florida State University professor of biological science, have conducted fieldwork in the Prince Creek Formation in northern Alaska. They have unearthed many dinosaur species, most of them new to science, from the bluffs above the Colville River.

Their latest discoveries are tiny teeth and bones from seven species of perinatal dinosaurs, a term that describes baby dinosaurs that are either just about to hatch or have just hatched.

"One of the biggest mysteries about Arctic dinosaurs was whether they seasonally migrated up to the North or were year-round denizens," said Erickson, a co-author of the paper. "We unexpectedly found remains of perinates representing almost every kind of dinosaur in the formation. It was like a prehistoric maternity ward."

Recovering the bones and teeth, some no larger than the head of a pin, requires perseverance and a sharp eye. In the field, the scientists hauled buckets of sediment from the face of the bluffs down to the river's edge, where they washed the material through smaller and smaller screens to remove large rocks and soil.

Once back at their labs, Druckenmiller, Erickson and co-author Jaelyn Eberle from the University of Colorado, Boulder, screened the material further. Then, teaspoon by teaspoon, the team, which included graduate and undergraduate students, examined the remaining sandy particles under microscopes to find the bones and teeth.

"Recovering these tiny fossils is like panning for gold," Druckenmiller said. "It requires a great amount of time and effort to sort through tons of sediment grain-by-grain under a microscope. The fossils we found are rare but are scientifically rich in information."

Next, the scientists worked with Caleb Brown and Don Brinkman from the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Alberta, Canada, to compare the fossils to those from other sites at lower latitudes. Those comparisons helped them conclude that the bones and teeth were from perinatal dinosaurs.

Once they knew the dinosaurs were nesting in the Arctic, they realized the animals lived their entire lives in the region.

Erickson's previous research revealed that the incubation period for these types of dinosaurs ranges from three to six months. Because Arctic summers are short, even if the dinosaurs laid their eggs in the spring, their offspring would be too young to migrate in the fall.

Global temperatures were much warmer during the Cretaceous, but the Arctic winters still would have included four months of darkness, freezing temperatures, snow and little fresh vegetation for food.

"As dark and bleak as the winters would have been, the summers would have had 24-hour sunlight, great conditions for a growing dinosaur if it could grow quickly enough before winter set in," said Brown, a paleontologist at the Royal Tyrrell Museum.

Year-round Arctic residency provides a natural test of the animals' physiology, Erickson added.

"We solved several long-standing mysteries about the dinosaur reign, but opened up a new can of worms," he said. "How did they survive Arctic winters?"

"Perhaps the smaller ones hibernated through the winter," Druckenmiller said. "Perhaps others lived off poor-quality forage, much like today's moose, until the spring."

Scientists have found warm-blooded animal fossils in the region, but no snakes, frogs or turtles, which were common at lower latitudes. That suggests the cold-blooded animals were poorly suited for survival in the cold temperatures of the region.

"This study goes to the heart of one of the longest-standing questions among paleontologists: Were dinosaurs warm-blooded?" Druckenmiller said. "We think that endothermy was probably an important part of their survival."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation.

The 'anterior cingulate cortex' is key brain region involved in linking behaviours to their outcomes.

When this region was temporarily silenced, monkeys did not change behaviour even when it stopped having the expected outcome.

The finding is a step towards targeted treatment of human disorders involving compulsive behaviour, such as OCD and eating disorders, thought to involve impaired function in this brain region.

Researchers have discovered a specific brain region underlying 'goal-directed behaviour' - that is, when we consciously do something with a particular goal in mind, for example going to the shops to buy food.

The ...

LA JOLLA, CA--New research led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) and the University of Liverpool may explain why many cancer patients do not respond to anti-PD-1 cancer immunotherapies--also called checkpoint inhibitors.

The team reports that these patients may have tumors with high numbers of T follicular regulatory (Tfr) cells.

In a healthy person, Tfr cells do the important job of stopping haywire T cells and autoantibodies from attacking the body's own tissues. But in a cancer patient, Tfr cells dramatically dial back the body's ability to kill cancer cells.

Anti-PD-1 cancer immunotherapies boost the body's cancer-fighting T cells, but ...

'Precision agriculture' where farmers respond in real time to changes in crop growth using nanotechnology and artificial intelligence (AI) could offer a practical solution to the challenges threatening global food security, a new study reveals.

Climate change, increasing populations, competing demands on land for production of biofuels and declining soil quality mean it is becoming increasingly difficult to feed the world's populations.

The United Nations (UN) estimates that 840 million people will be affected by hunger by 2030, but researchers have developed a roadmap combining smart and nano-enabled agriculture with AI and machine learning capabilities that could help to reduce this ...

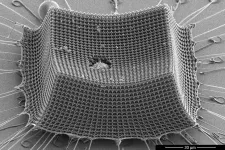

A new study by engineers at MIT, Caltech, and ETH Zürich shows that "nanoarchitected" materials -- materials designed from precisely patterned nanoscale structures -- may be a promising route to lightweight armor, protective coatings, blast shields, and other impact-resistant materials.

The researchers have fabricated an ultralight material made from nanometer-scale carbon struts that give the material toughness and mechanical robustness. The team tested the material's resilience by shooting it with microparticles at supersonic speeds, and found that the material, which is thinner than the width of a human hair, prevented the miniature projectiles from tearing through ...

HAMILTON, ON June 24, 2021 -- The idea of visiting the doctor's office with symptoms of an illness and leaving with a scientifically confirmed diagnosis is much closer to reality because of new technology developed by researchers at McMaster University.

Engineering, biochemistry and medical researchers from across campus have combined their skills to create a hand-held rapid test for bacterial infections that can produce accurate, reliable results in less than an hour, eliminating the need to send samples to a lab.

Their proof-of-concept research, published today in the journal Nature Chemistry, specifically describes the test's ...

In a few years, a new generation of quantum simulators could provide insights that would not be possible using simulations on conventional supercomputers. Quantum simulators are capable of processing a great amount of information since they quantum mechanically superimpose an enormously large number of bit states. For this reason, however, it also proves difficult to read this information out of the quantum simulator. In order to be able to reconstruct the quantum state, a very large number of individual measurements are necessary. The method used to read out the quantum state of a ...

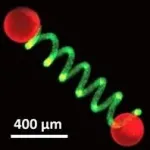

A University of Bristol-led team of international scientists with an interest in protoliving technologies, has today published research which paves the way to building new semi-autonomous devices with potential applications in miniaturized soft robotics, microscale sensing and bioengineering.

Micro-actuators are devices that can convert signals and energy into mechanically driven movement in small-scale structures and are important in a wide range of advanced microscale technologies.

Normally, micro-actuators rely on external changes in bulk properties such as pH and temperature to trigger repeatable mechanical ...

What The Study Did: Researchers found no association between recent vaccination with the Pfizer-BioNTech BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine and risk of facial nerve palsy.

Authors: Asaf Shemer, M.D., of the Shamir Medical Center in Be'er Ya'akov, Israel, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2021.1259)

Editor's Note: Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media ...

What The Study Did: Researchers estimated the change in life expectancy associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States by race/ethnicity.

Authors: Theresa Andrasfay, Ph.D., of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.14520)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study is linked to this news release.

Embed ...

What The Study Did: Patients with COVID-19-related loss of smell were evaluated for one year after the diagnosis.

Authors: Marion Renaud, M.D., of University Hospitals of Strasbourg, France, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15352)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study is linked to this news release.

Embed this link to provide ...