(Press-News.org) A study from UCLA neurologists challenges the idea that the brain recruits existing neurons to take over for those that are lost from stroke. It shows that in mice, undamaged neurons do not change their function after a stroke to compensate for damaged ones.

A stroke occurs when the blood supply to a certain part of the brain is interrupted, such as by a blood clot. Brain cells in that area become damaged and can no longer function.

A person who is having a stroke may temporarily lose the ability to speak, walk, or move their arms. Few patients recover fully and most are left with some disability, but the majority exhibit some degree of spontaneous recovery during the first few weeks after the stroke.

Doctors and scientists don't fully understand how this happens, because the brain does not grow new cells to replace the ones damaged by the stroke. Neurologists have generally assumed that the brain instead recruits existing neurons to take over for those that are lost.

Now, new results from neurologists William Zeiger and Carlos Portera-Cailliau from the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA challenge that idea. In their paper, published June 25 in the journal Nature Communications, they show that in mice, undamaged neurons do not change their function after a stroke to compensate for damaged ones.

Neurologists have been "mapping" the brain since the mid-1800s, when the French physician Paul Broca realized that patients who sustained damage to a certain part of the frontal lobe lost the ability to speak. Over the years, scientists have created increasingly detailed maps of which brain regions control various functions. Still, the resolution of the map has been limited by the precision of the tools available to study the living brain.

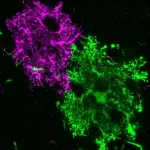

Studies in animals and humans that recorded activity across different brain regions have found that activity patterns change after a stroke, suggesting that the damaged brain can "re-map" functions from one area to another. In the last few years, innovative new tools have enabled researchers to start looking at individual neuron activation in real-time. By using a technique called two-photon fluorescence microscopy that causes neurons to light up when they are activated, researchers can observe which neurons in the animal brain are called upon during certain activities and determine if neurons that survived a stroke can assume the function of those that were lost.

"We thought, now that we have this tool where we can record the activity of neurons in the brain, we could directly test this question," says Zeiger. By learning the functions of individual neurons, then causing a targeted stroke, the researchers could use the new technique to observe how the neighboring neurons responded.

Mice gather information about their environment primarily through their whiskers, and each whisker transmits sensory signals to a specific group of neurons. By destroying the neurons coded to a specific whisker, the researchers could look at whether neurons for a different whisker took over for their lost neighbors.

Think of a departmental office, says Portera-Cailliau. "Imagine that several admin staff in human resources for the Department of Neurology suddenly quit their jobs one day. Instantly, the department would suffer their absence, but would try to make up for it." The department might do this by asking HR employees from other departments to do some of the missing employees' work on top of their own.

That's what the re-mapping hypothesis predicts would happen in the brain. "If the hypothesis were true, we would see cells that survived the stroke start to respond to that whisker that had the stroke," Zeiger says. "What we found was that that didn't happen."

Adjacent to the main column of neurons that respond to a given whisker are neurons called "surround-responsive" cells. These are located in the column for one whisker, but they react to the stimulation of a neighboring whisker. Using the office analogy, these neurons would be like employees that work on HR but happen to have their desks in a different physical office.

Logically, then, the team thought that the surround-responsive neurons would be good candidates to take over when the primary responding neurons were destroyed by the stroke. "If the HR office suddenly shut down, you might think more people in these other offices would start doing human resource jobs," Portera-Cailliau says. Yet not only did these other neurons fail to step up, the activity of the surround-responsive neurons themselves decreased after the stroke.

"That was pretty strong evidence against this remapping hypothesis," Zeiger says. "It did not seem like there was bulk recruitment to take over the function which had been lost to stroke."

More studies will be needed to gain a full understanding of what happens in the human brain after a stroke, including why spontaneous recovery happens. Zeiger says that future studies could also explore various ways to induce the surviving cells to compensate for the lost neurons.

"I think it gives the field more of a direction," Zeiger says. "Rather than assuming the brain can remap on its own, now we know that to achieve full recovery, we're going to need a way to get cells to do things they are not already doing."

INFORMATION:

A near-perfectly preserved ancient human fossil known as the Harbin cranium sits in the Geoscience Museum in Hebei GEO University. The largest of known Homo skulls, scientists now say this skull represents a newly discovered human species named Homo longi or "Dragon Man." Their findings, appearing in three papers publishing June 25 in the journal The Innovation, suggest that the Homo longi lineage may be our closest relatives--and has the potential to reshape our understanding of human evolution.

"The Harbin fossil is one of the most complete human cranial fossils in the world," says author Qiang Ji, a professor of paleontology of Hebei GEO University. "This fossil preserved many ...

WASHINGTON--Antacids improved blood sugar control in people with diabetes but had no effect on reducing the risk of diabetes in the general population, according to a new meta-analysis published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Type 2 diabetes is a global public health concern affecting almost 10 percent of people worldwide. Doctors may prescribe diet and lifestyle changes, diabetes medications, or insulin to help people with diabetes better manage their blood sugar, but recent data points to common over the counter ...

What The Study Did: This study evaluated changes in hospitalization and death rates related to COVID-19 before and after U.S. states reopened their economies in 2020.

Authors: Pinar Karaca-Mandic, Ph.D., of the Carlson School of Management in Minneapolis, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1262)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study ...

What The Study Did: Researchers examined the association of closures of childcare facilities with the employment status of women and men with children in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors: Yevgeniy Feyman, B.A., of the Boston University School of Public Health, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1297)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author ...

What The Study Did: This analysis describes the use of a multifaceted COVID-19 control plan to reduce spread of SARS-CoV-2 at a large urban university during the second wave of the pandemic.

Authors: Davidson H. Hamer, M.D., of the Boston University School of Public Health, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16425)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and ...

What The Study Did: Researchers looked at whether age-related hearing impairment among older adults is associated with poorer and faster decline in physical function and reduced walking endurance.

Authors: Pablo Martinez-Amezcua, M.D., Ph.D., M.H.S., of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13742)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media ...

Scientists of Tomsk Polytechnic University jointly with their colleagues have synthetized a unique molecule of verdazyl-nitronyl nitroxide triradical. Only several research teams in the world were able to obtain molecules with similar properties. The molecule is stable. It is able to withstand high temperatures and obtains promising magnetic properties. It is a continuation of scientists' work on the search for promising organic magnetic materials. The research findings are published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society (IF: 14.612, Q1).

Magnetoresistive random-access memory (MRAM) is one of the most promising technologies for storage devices. ...

CHAPEL HILL, NC - When we think of the brain, we think of neurons. But much of the brain is made of non-neuronal cells called glial cells, which help regulate brain development and function. For the first, time UNC School of Medicine scientist Katie Baldwin, PhD, and colleagues revealed a central role of the glial protein hepaCAM in building the brain and affecting brain function early in life.

The findings, published in Neuron, have implications for better understanding disorders, such as autism, epilepsy, and schizophrenia, and potentially for creating therapeutics for conditions such as the progressive brain disorder megalencephalic ...

TAMPA, Fla. -- E-cigarettes spark many concerns, especially when it comes to youth vaping. However, emerging evidence suggests that e-cigarettes can be a helpful tool in smoking cessation. Researchers in Moffitt Cancer Center's Tobacco Research and Intervention Program wanted to build upon this evidence by testing whether they could help dual users, people who use both combustible cigarettes and e-cigarettes, quit smoking. In a new article published in The Lancet Public Health, they report results from a first-of-its kind nationwide study evaluating a targeted intervention aimed at transforming dual users' e-cigarettes from a product that might ...

CHAPEL HILL, NC - Developing a viable vaccine against dengue virus has proved difficult because the pathogen is actually four different virus types, or serotypes. Unless a vaccine protects against all four, a vaccine can wind up doing more harm than good.

To help vaccine developers overcome this hurdle, the UNC School of Medicine lab of Aravinda de Silva, PhD, professor in the UNC Department of Microbiology and Immunology, investigated samples from children enrolled in a dengue vaccine trial to identify the specific kinds of antibody responses that correlate with ...