One "Ring" to rule them all: curious interlocked molecules show dual response

2021-06-25

(Press-News.org) Scientists at Tokyo Institute of Technology design polymers infused with a stress-sensitive molecular unit that respond to external forces by switching on their fluorescence. The researchers demonstrate the fluorescence to be dependent on the magnitude of force and show that it is possible to detect both, reversible and irreversible polymer deformations, opening the door to the exploration of new force regimes in polymers.

Besides causing physical motion, mechanical forces can drive chemical changes in controlled and productive ways, allowing for desirable material properties. One way to go about this is by introducing a so-called mechanophore into the material, molecular units that are sensitive to stress or strain. Specifically, mechanochromic mechanophores, which alter their optical properties in response to mechanical stimuli, are quite useful in quantifying their local mechanical environment.

However, the response mechanism at play in most mechanophores involves severing of chemical bonds. Consequently, they require relatively large mechanical forces to be activated and their response is usually not reversible. To address these issues, researchers led by Prof. Yoshimitsu Sagara from Tokyo Institute of Technology (Tokyo Tech) had previously developed supramolecular mechanophores that show instantly reversible on/off switching of fluorescence without any scission of covalent bonds. The team's next challenge was to determine if both reversible and irreversible mechanoresponses can be elicited from the same molecular motif.

In a new Journal of the American Chemical Society study, the team explores this question using an unusual molecular architecture called "rotaxane" in which a dumbbell-shaped molecule is threaded through a "ring" such that they are mechanically interlocked, i.e. the "ring" cannot be normally pulled out. By attaching a quencher-emitter pair to the rotaxane and selecting appropriate sizes of ring and stopper moieties, the team demonstrates a new type of mechanophore response that can be either reversible or irreversible, depending on the magnitude of the applied force (Figure 1).

"When there is no force applied, the attractive interaction keeps the emitter-containing ring near the quencher fixed on the rotaxane's axle, so that the emission is quenched," explains Sagara. "Upon applying a weak force, the emitter is moved away from the quencher, and its fluorescence is turned on. This effect is reversible, unless the force is sufficiently high to push the ring past the stopper so that irreversible dethreading occurs."

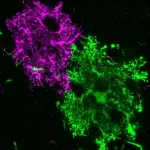

By investigating a carefully designed set of different rotaxanes, the team demonstrated that the combination of appropriately selected ring and stopper moieties having the right sized is crucial to obtain interlocked structures that display such dual response. Tokyo Tech researchers collaborated with Swiss partners from the University of Fribourg's Adolphe Merkle Institute to incorporate the new mechanophores into elastic polyurethane rubbers. These materials which exhibit reversible fluorescence changes over many stretch-and-release cycles to low strains, due to the shuttling function, whereas permanent changes were observed when the rubbers were subjected to repeated deformations to high strains due to dethreading of the ring from the axle. "This mechanism allows one, at least conceptually, to monitor the actual deformation of polymer materials and examine mechanical damage that were inflicted in the past on the basis of an optical signal" says Sagara.

Speculating the possible implications of their results, an elated Sagara comments, "Extending the current library of mechanophores with our rotaxane-based candidates would be useful for studying the mechanical properties of not only polymers but also cells and tissues, as our mechanophores can respond to much smaller forces compared to those involving chemical bond scission."

Simply put, rotaxanes could pervade all of natural science!

INFORMATION:

About Tokyo Institute of Technology

Tokyo Tech stands at the forefront of research and higher education as the leading university for science and technology in Japan. Tokyo Tech researchers excel in fields ranging from materials science to biology, computer science, and physics. Founded in 1881, Tokyo Tech hosts over 10,000 undergraduate and graduate students per year, who develop into scientific leaders and some of the most sought-after engineers in industry. Embodying the Japanese philosophy of "monotsukuri," meaning "technical ingenuity and innovation," the Tokyo Tech community strives to contribute to society through high-impact research.

https://www.titech.ac.jp/english/

About Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST)

Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), an advanced network-based research institute that promotes the state-of-the-art R&D projects, will boldly lead the way for co-creation of innovation for tomorrow's world together with society.

https://www.jst.go.jp/EN/

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-25

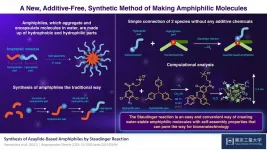

Amphiphilic molecules, which aggregate and encapsulate molecules in water, find use in several fields of chemistry. The simple, additive-free connection of hydrophilic and hydrophobic molecules would be an efficient method for amphiphilic molecule synthesis. However, such connections, or bonds, are often fragile in water. Now, scientists at Tokyo Institute of Technology have developed an easy way to prepare water-stable amphiphiles by simple mixing. Their new catalyst- and reagent-free method will help create further functional materials.

Soaps and detergents are used to clean things like clothes and dishes. But how do they actually work? It turns out that they are made of long molecules ...

2021-06-25

A study from UCLA neurologists challenges the idea that the brain recruits existing neurons to take over for those that are lost from stroke. It shows that in mice, undamaged neurons do not change their function after a stroke to compensate for damaged ones.

A stroke occurs when the blood supply to a certain part of the brain is interrupted, such as by a blood clot. Brain cells in that area become damaged and can no longer function.

A person who is having a stroke may temporarily lose the ability to speak, walk, or move their arms. Few patients recover fully and most are left with some disability, but the majority exhibit some degree of spontaneous recovery during the first few weeks after the stroke.

Doctors and scientists don't fully ...

2021-06-25

A near-perfectly preserved ancient human fossil known as the Harbin cranium sits in the Geoscience Museum in Hebei GEO University. The largest of known Homo skulls, scientists now say this skull represents a newly discovered human species named Homo longi or "Dragon Man." Their findings, appearing in three papers publishing June 25 in the journal The Innovation, suggest that the Homo longi lineage may be our closest relatives--and has the potential to reshape our understanding of human evolution.

"The Harbin fossil is one of the most complete human cranial fossils in the world," says author Qiang Ji, a professor of paleontology of Hebei GEO University. "This fossil preserved many ...

2021-06-25

WASHINGTON--Antacids improved blood sugar control in people with diabetes but had no effect on reducing the risk of diabetes in the general population, according to a new meta-analysis published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

Type 2 diabetes is a global public health concern affecting almost 10 percent of people worldwide. Doctors may prescribe diet and lifestyle changes, diabetes medications, or insulin to help people with diabetes better manage their blood sugar, but recent data points to common over the counter ...

2021-06-25

What The Study Did: This study evaluated changes in hospitalization and death rates related to COVID-19 before and after U.S. states reopened their economies in 2020.

Authors: Pinar Karaca-Mandic, Ph.D., of the Carlson School of Management in Minneapolis, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1262)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study ...

2021-06-25

What The Study Did: Researchers examined the association of closures of childcare facilities with the employment status of women and men with children in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Authors: Yevgeniy Feyman, B.A., of the Boston University School of Public Health, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2021.1297)

Editor's Note: The article includes funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author ...

2021-06-25

What The Study Did: This analysis describes the use of a multifaceted COVID-19 control plan to reduce spread of SARS-CoV-2 at a large urban university during the second wave of the pandemic.

Authors: Davidson H. Hamer, M.D., of the Boston University School of Public Health, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.16425)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and ...

2021-06-25

What The Study Did: Researchers looked at whether age-related hearing impairment among older adults is associated with poorer and faster decline in physical function and reduced walking endurance.

Authors: Pablo Martinez-Amezcua, M.D., Ph.D., M.H.S., of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13742)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media ...

2021-06-25

Scientists of Tomsk Polytechnic University jointly with their colleagues have synthetized a unique molecule of verdazyl-nitronyl nitroxide triradical. Only several research teams in the world were able to obtain molecules with similar properties. The molecule is stable. It is able to withstand high temperatures and obtains promising magnetic properties. It is a continuation of scientists' work on the search for promising organic magnetic materials. The research findings are published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society (IF: 14.612, Q1).

Magnetoresistive random-access memory (MRAM) is one of the most promising technologies for storage devices. ...

2021-06-25

CHAPEL HILL, NC - When we think of the brain, we think of neurons. But much of the brain is made of non-neuronal cells called glial cells, which help regulate brain development and function. For the first, time UNC School of Medicine scientist Katie Baldwin, PhD, and colleagues revealed a central role of the glial protein hepaCAM in building the brain and affecting brain function early in life.

The findings, published in Neuron, have implications for better understanding disorders, such as autism, epilepsy, and schizophrenia, and potentially for creating therapeutics for conditions such as the progressive brain disorder megalencephalic ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] One "Ring" to rule them all: curious interlocked molecules show dual response