(Press-News.org) All life on Earth 500 million years ago lived in the oceans, but scientists know little about how these animals and algae developed. A newly discovered fossil deposit near Kunming, China, may hold the keys to understanding how these organisms laid the foundations for life on land and at sea today, according to an international team of researchers.

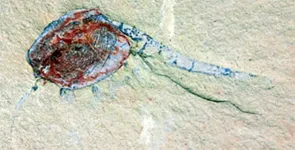

The fossil deposit, called the Haiyan Lagerstätte, contains an exceptionally preserved trove of early vertebrates and other rare, soft-bodied organisms, more than 50% of which are in the larval and juvenile stages of development. Dating to the Cambrian geologic period approximately 518 million years ago and providing researchers with 2,846 specimens so far, the deposit is the oldest and most diverse found to date.

"It's just amazing to see all these juveniles in the fossil record," said Julien Kimmig, collections manager at the Earth and Mineral Sciences Museum & Art Gallery, Penn State. "Juvenile fossils are something we hardly see, especially from soft-bodied invertebrates."

Xianfeng Yang, a paleobiologist at Yunnan University, China, led a team of Chinese researchers that collected the fossils at the research site. He measured and photographed the specimens and analyzed them with Kimmig. The researchers report the results of their study today (June 28) in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

The researchers identified 118 species, including 17 new species, in the lagerstätte -- a sedimentary deposit of extraordinary fossils with exceptional preservation that sometimes includes preserved soft tissues.

The species include the ancestors of modern-day insects and crustaceans, worms, trilobites, algae, sponges and early vertebrates related to jawless fish. The researchers also found eggs and an abundance of rare juvenile fossils with appendages still intact and their internal soft tissues visible.

The specimens are so well-preserved that they are revealing body parts never before seen, said Sara Kimmig, assistant research professor in the Earth and Environmental Systems Institute and facility director of the Laboratory for Isotopes and Metals in the Environment at Penn State.

"The site preserved details like 3D eyes, features that have never really been seen before, especially in such early deposits," she said.

Scientists can use CT scanning on these 3D features to reconstruct the animals and extract even more information from the fossils, according to the researchers.

The lagerstätte contains several event beds, or layers in the sediment where the fossils are found. Each layer represents a single burial event. All species identified in the study are present in the lowest layer, with subsequent layers containing diverse species, but not to the extent of the lowest one.

The researchers think these intervals could represent boom and bust periods in the marine community. Many species might have come to the area -- at the time located in deeper waters toward the center of the Kunming Gulf -- seeking protection from strong ocean currents. However, a change in oxygen levels or storm events that caused sediment to flow down a slope and bury everything in its path may have caused extinctions.

The abundance of juvenile fossils, on the other hand, suggests that the Haiyan Lagerstätte could have been a paleonursery. The species found in the lagerstätte may have chosen to reproduce there due to the protection it provided from predators.

"Could these worms and jellyfish and bugs have developed something as sophisticated as a paleonursery to raise their young? Whatever the case may be, it's fascinating to be able to parallel this behavior to that of modern animals," Sara Kimmig said.

Scientists will be able to use this collection to study how these ancient animals developed from the larval to the adult stage.

"We'll see how different body parts grew over time, which is something we currently do not know for most of these groups," Julien Kimmig said. "And these fossils will give us more information on their relationships to modern animals. We will see if how these animals develop today is similar to how they developed 500 million years ago, or if something has changed throughout time."

The developmental information will also provide insights into the relationships between animal groups, as similar developmental patterns may indicate a link between species, he added.

"The Haiyan Lagerstätte will be a wealth of knowledge moving forward for many researchers, not only in terms of paleontology but also in paleo-environmental reconstructions," said Sara Kimmig. She and her colleagues would like to conduct geochemical analyses on the specimens and the sediments. These analyses could help them potentially recreate the environment and climate during the time that this lagerstätte was deposited.

The fossils will also allow the researchers to study how animals behaved 500 million years ago when the world was a bit warmer than today and use it as a proxy for where the world is headed in terms of animal behavior in a warmer environment.

"In this deposit, we found the ancestors to most modern animals, both marine and terrestrial," Julien Kimmig said. "If the Haiyan Lagerstätte is actually a paleonursery, it means that this type of animal behavior has not changed much in 518 million years."

INFORMATION:

Additional contributors to this study include Dayou Zhai and Yu Liu, Yunnan University; and Shanchi Peng, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The National Natural Science Foundation of China, the State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy at the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology, and the Key Research Program of the Institute of Geology & Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, funded this research.

The world of microbes living in the human gut can have far-reaching effects on human health. Multiple diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), are tied to the balance of these microbes, suggesting that restoring the right balance could help treat disease. Many probiotics -- living yeasts or bacteria -- that are currently on the market have been optimized through evolution in the context of a healthy gut. However, in order to treat complex diseases such as IBD, a probiotic would need to serve many functions, including an ability to turn off inflammation, reverse damage and restore the gut microbiome. Given all of these needs, researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital have developed a "designer" ...

A new discovery in rats shows that the brain responds differently in immersive virtual reality environments versus the real world. The finding could help scientists understand how the brain brings together sensory information from different sources to create a cohesive picture of the world around us. It could also pave the way for "virtual reality therapy" for learning and memory-related disorders ranging including ADHD, Autism, Alzheimer's disease, epilepsy and depression.

Mayank Mehta, PhD, is the head of W. M. Keck Center for Neurophysics and a professor in the departments of physics, neurology, and electrical and computer engineering at UCLA. His laboratory studies a brain region called the hippocampus, which is a primary driver of learning and memory, ...

An international team of astronomers has observed the first example of a new type of supernova. The discovery, confirming a prediction made four decades ago, could lead to new insights into the life and death of stars. The work is published June 28 in Nature Astronomy.

"One of the main questions in astronomy is to compare how stars evolve and how they die," said Stefano Valenti, professor of physics and astronomy at the University of California, Davis, and a member of the team that discovered and described supernova 2018zd. "There are many links still missing, so this is very exciting."

There ...

NEW YORK, NY (June 28, 2021)--In the first analysis of its kind, researchers at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and several other institutions have linked distinct patterns of genetic mutations with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in humans.

The work, published online June 28 in Nature Neuroscience, confirms the validity of targeting specific genes to develop new OCD treatments and points toward novel avenues for studying this often debilitating condition.

OCD, which affects 1% to 2% of the population, often runs in families and genes are known to play a large role in determining who develops the disease. However, the identity of many OCD genes remains unknown.

"Many neurological diseases are ...

Slow earthquakes are long-period earthquakes that are not so dangerous alone, but are able to trigger more destructive earthquakes. Their origins lie in tectonic plate boundaries where one plate subsides below another. Though the causal mechanism is already known, there has been a lack of data to accurately model the life cycle of slow earthquakes. For the first time, researchers use deep-sea boreholes to gauge pressures far below the seafloor. They hope data from this and future observations can aid the understanding of earthquake evolution.

The surface of the Earth lies upon gargantuan ...

New York, NY--June 28, 2021--Predicting what someone is about to do next based on their body language comes naturally to humans but not so for computers. When we meet another person, they might greet us with a hello, handshake, or even a fist bump. We may not know which gesture will be used, but we can read the situation and respond appropriately.

In a new study, Columbia Engineering researchers unveil a computer vision technique for giving machines a more intuitive sense for what will happen next by leveraging higher-level associations between people, animals, and objects.

"Our algorithm is a step toward machines being able to make better predictions about human behavior, and ...

Sixteen of the 146 health-related All-Party Parliamentary Groups (APPGs) in the Houses of Parliament (UK) received over a £1 million in payments from 35 pharmaceutical companies between 2012-2018 according to a new study.

The researchers behind the analysis from the University of Bath's Centre for the Analysis of Social Policy suggest their findings reveal a worrying lack of transparency over payments received and potential conflicts of interests towards public policy.

Through their research they extracted details from 6,624 entries about funding ...

Experts estimate more than 6 million Americans are living with Alzheimer's dementia. But a recent study, led by the University of Cincinnati, sheds new light on the disease and a highly debated new drug therapy.

The UC-led study, conducted in collaboration with the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, claims that the treatment of Alzheimer's disease might lie in normalizing the levels of a specific brain protein called amyloid-beta peptide. This protein is needed in its original, soluble form to keep the brain healthy, but sometimes it hardens into "brain stones" or clumps, called amyloid plaques.

The study, which appears in the journal EClinicalMedicine (published by the Lancet), comes on the heels of the FDA's conditional approval of a new medicine, aducanumab, that ...

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Oregon State University researchers have some good news for the well-meaning masses who place bird feeders in their yards: The small songbirds who visit the feeders seem unlikely to develop an unhealthy reliance on them.

"There's still much we don't know about how intentional feeding might induce changes in wild bird populations, but our study suggests that putting out food for small birds in winter will not lead to an increased dependence on human-provided food," said Jim Rivers, an animal ecologist with the OSU College of Forestry.

Findings from the research, which looked at black-capped chickadees outfitted with radio frequency identification tags, ...

New York, NY (June 28, 2021) - Patients with a type of blood cancer called multiple myeloma had a widely variable response to COVID-19 vaccines--in some cases, no detectable response--pointing to the need for antibody testing and precautions for these patients after vaccination, according to a study that will be published in Cancer Cell this week.

Mount Sinai researchers found that multiple myeloma patients mount variable and sometimes suboptimal responses after receiving the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna COVID-19 vaccines. Almost 16 percent of these patients developed no detectible antibodies after both vaccine doses. These findings may be relevant to other cancer patients undergoing treatment and to immunocompromised patients.

"This study ...