Scientists intensify electrolysis, utilize carbon dioxide more efficiently with magnets

2021-06-30

(Press-News.org) For decades, researchers have been working toward mitigating excess atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. One promising approach captures atmospheric CO2 and then, through CO2 electrolysis, converts it into value-added chemicals and intermediates--like ethanol, ethylene, and other useful chemicals. While significant research has been devoted to improving the rate and selectivity of CO2 electrolysis, reducing the energy consumption of this high-power process has been underexplored.

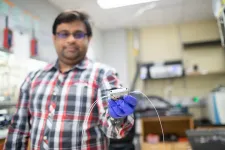

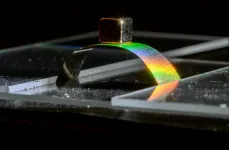

In ACS Energy Letters, researchers from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign report a new opportunity to use magnetism to reduce the energy required for CO2 electrolysis by up to 60% in a flow electrolyzer.

In a typical CO2 flow electrolyzer, electricity is supplied to drive the reactions at the cathode (where carbon dioxide is reduced into useful byproducts) and the anode (where water is oxidized, producing oxygen).

Most studies have focused on making the reduction reaction at the cathode more efficient at higher rates; however, this process requires little energy compared to the oxidation reaction on the anode--which often accounts for more than 80% of the energy required for CO2 electrolysis, and therefore, offers the most room for improvement.

"The answer was staring us right in the face--of course, the trick is to reduce the energy consumption at the anode," said first-author Saket S. Bhargava, a graduate student in chemical and biomolecular engineering at Illinois. "We decided that if oxygen evolution is the problem, why not use a magnetic field at the oxygen evolving electrode and see what happens to the entire system."

They used a magnetic field at the anode to achieve energy savings ranging from 7% to 64% by enhancing mass transport to/from the electrode. They also swapped the traditional iridium catalyst--a precious metal--with a nickel-iron catalyst comprised of abundant elements.

"Our ultimate goal is to transform carbon dioxide back into carbon-based chemicals," said lead author Paul Kenis, a chemical and biomolecular engineering professor and department head at Illinois. "With this study, we have demonstrated how further to reduce the significant energy requirements for CO2 electrolysis, hopefully making this process more viable for adoption by industry."

INFORMATION:

The Link Foundation, 3M, and Shell supported this research through student fellowships. Co-authors also include University of Illinois students Daniel Azmoodeh, Xinyi Chen, Emiliana R. Cofell, Anne Marie Esposito, Sumit Verma, and Andrew A. Gewirth, professor of chemistry.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-06-30

PULLMAN, Wash. - Fire can put a tropical songbird's sex life on ice.

Following habitat-destroying wildfires in Australia, researchers found that many male red-backed fairywrens failed to molt into their red-and-black ornamental plumage, making them less attractive to potential mates. They also had lowered circulating testosterone, which has been associated with their showy feathers.

For the study published in the Journal of Avian Biology, the researchers also measured the birds' fat stores and the stress hormone corticosterone but found those remained at normal levels.

"Really, it ended up all coming down to testosterone," said ...

2021-06-30

Male jackdaws don't stick around to console their mate after a traumatic experience, new research shows.

Jackdaws usually mate for life and, when breeding, females stay at the nest with eggs while males gather food.

Rival males sometimes visit the nest and attack the lone female, attempting to mate by force.

In the new study, University of Exeter researchers expected males to console their partner after these incidents by staying close and engaging in social behaviours like preening their partner's feathers.

However, males focussed on their own safety - they still brought food to the nest, but they visited less often and spent less time with the female.

"Humans often console friends or family in distress, but it's unclear whether animals do this in the wild," said Beki ...

2021-06-30

A new analysis of 58 studies and 44305 patients published in Anaesthesia (a journal of the Association of Anaesthetists) shows that, contrary to some previous research, being male and increasing body mass index (BMI) are not associated with increased mortality in COVID-19 in patients admitted into intensive care (ICU).

However, the study, by Dr Bruce Biccard (Groote Schuur Hospital and University of Cape Town, South Africa) and colleagues finds that a wide range of factors are associated with death from COVID-19 in ICU.

Patients with COVID-19 in ICU were 40% more likely to die with a history of smoking, 54% more likely with high blood pressure, 41% more likely with diabetes, ...

2021-06-30

This year marks the 100th anniversary of the discovery of insulin, a scientific breakthrough that transformed Type 1 diabetes, once known as juvenile diabetes or insulin-dependent diabetes, from a terminal disease into a manageable condition.

Today, Type 2 diabetes is 24 times more prevalent than Type 1. The rise in rates of obesity and incidence of Type 2 diabetes are related and require new approaches, according to University of Arizona researchers, who believe the liver may hold the key to innovative new treatments.

"All current therapeutics for ...

2021-06-30

Los Angeles, Calif. - The AIDS Clinical Trials Group (ACTG), the largest global HIV research network, today announced that findings from a sub-study of REPRIEVE (A5332/A5332s, an international clinical trial studying heart disease prevention in people living with HIV) have been published in the Journal of the American Medical Association Network Open (JAMA Network Open). The study found that approximately half of study participants, who were considered by traditional measures to be at low-to-moderate risk of future heart disease, had atherosclerotic plaque in their coronary arteries.

While it is well-known that people living with HIV are at ...

2021-06-29

(OTTAWA, ON) The University of Ottawa, the University of Montreal and the Assembly of First Nations are pleased to announce the newly published First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study (FNFNES) in the Canadian Journal of Public Health. Mandated by First Nations leadership across Canada through Assembly of First Nations Resolution 30 / 2007 and realized through a unique collaboration with researchers and communities, the First Nations Food, Nutrition and Environment Study is the first national study of its kind. It was led by principal investigators Dr. Laurie Chan, a professor ...

2021-06-29

UCLA engineers have demonstrated successful integration of a novel semiconductor material into high-power computer chips to reduce heat on processors and improve their performance. The advance greatly increases energy efficiency in computers and enables heat removal beyond the best thermal-management devices currently available.

The research was led by Yongjie Hu, an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at the UCLA Samueli School of Engineering. Nature Electronics recently published the finding in this article.

Computer processors have shrunk down to nanometer scales over the years, with billions of transistors sitting on a single computer chip. While the increased number of transistors helps make computers faster and more powerful, it also generates ...

2021-06-29

Scientists and doctors at University College London Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health (UCL GOS ICH) and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) have given hope of a gene therapy cure to children with a rare degenerative brain disorder called Dopamine Transporter Deficiency Syndrome (DTDS).

The team have recreated and cured the disease using state-of-the-art laboratory and mouse models of the disease and will soon apply for a clinical trial of the therapy. Their breakthrough comes just a decade after the faulty gene causing the disease was first discovered by the lead scientist of this work.

The results, published in Science Translational Medicine, are so promising that the UK regulatory agency MHRA has advised ...

2021-06-29

Boulder, Colo., USA: Article topics include the Great Unconformity of the

Rocky Mountain region; new Ediacara-type fossils; the southern Cascade arc

(California, USA); the European Alps and the Late Pleistocene glacial

maximum; Permian-Triassic ammonoid mass extinction; permafrost thaw; the

southern Rocky Mountains of Colorado (USA); "gargle dynamics"; invisible

gold; and alluvial fan deposits in Valles Marineris, Mars. These Geology articles are online at

https://geology.geoscienceworld.org/content/early/recent

.

A new kind of invisible gold in pyrite hosted in deformation-related

dislocations

Denis Fougerouse; Steven M. Reddy; Mark ...

2021-06-29

Natural wood remains a ubiquitous building material because of its high strength-to-density ratio; trees are strong enough to grow hundreds of feet tall but remain light enough to float down a river after being logged.

For the past three years, engineers at the University of Pennsylvania's School of Engineering and Applied Science have been developing a type of material they've dubbed "metallic wood." Their material gets its useful properties and name from a key structural feature of its natural counterpart: porosity. As a lattice of nanoscale nickel struts, metallic wood is full of regularly spaced cell-sized pores that radically decrease its density without sacrificing the material's ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Scientists intensify electrolysis, utilize carbon dioxide more efficiently with magnets