"Now we've got a way to modify chloroplast genes specifically and measure their potential to make a good plant," said Associate Professor Shin-ichi Arimura, who leads the group that performed the research.

Chloroplasts, the parts of plant cells that convert carbon dioxide and sunlight into sugar, possess their own circular DNA that is made of the same ATGC-code as the double helix DNA in the nucleus of the cell. However, chloroplast DNA is maintained and inherited completely separately from nuclear DNA. Every cell can contain multiple chloroplasts, each with many identical copies of the chloroplast DNA. The same change must be made in every copy of chloroplast DNA if any genome editing is to have a noticeable effect that can be inherited by the plant's offspring.

In the 1990s, experts invented a technique to insert new DNA fragments into chloroplast genomes, but it also inserts extra genetic tags or markers.

The goal of Arimura and his colleagues is to make uniform, inheritable modifications to only specific parts of chloroplast DNA without leaving genome editing tools behind or permanently altering nuclear DNA. They started with an existing tool known as TALENs. The original TALENs use a large protein that recognizes specific short DNA sequences and cuts that DNA with an enzyme. In recent years, other research groups have improved TALEN technology: the DNA recognition sequences can be customized and the DNA cutting enzyme can be replaced with an enzyme that changes GC pairs in the DNA code into AT pairs.

These GC to AT changes are subtle -- just changing one point of the DNA code to another, rather than inserting or deleting whole genes. However, point mutations can have major effects depending on their location.

Arimura's team combined these TALEN improvements and added an extra "chloroplast-targeting" component, calling their finalized version ptpTALECDs. For every genome edit that researchers wanted to make, they needed to build a matching left and right pair of ptpTALECDs in bacteria. The design process is complicated because the pairs of large TALENs proteins and the chloroplast-targeting signals must be expressed simultaneously as a single unit from the nuclear DNA.

"Building the ptpTALECDs was an extremely laborious process, but we have a very dedicated master's degree student who did almost all the work, Issei Nakazato," said Arimura. Nakazato is the first author of the research publication.

After designing the ptpTALECDs DNA sequence, researchers then inserted it into Arabidopsis thaliana plants, a species of thale cress common in research laboratories. The UTokyo researchers are confident that after building them, the ptpTALECDs could be inserted into many crop species because that part of the process is a straightforward and standard procedure in agriculture and botany labs.

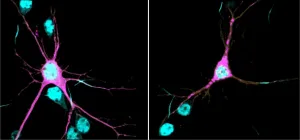

The ptpTALECDs enter the plants' nuclei and then the cells produce ptpTALECDs in the same way they produce any other protein. The chloroplast-targeting sequence ensures that the finished ptpTALECD proteins are shuttled out of the nucleus into the chloroplasts where they then are expected to edit every chloroplast genome they encounter.

This first generation plants are considered genetically modified organisms (GMOs) because their nuclear DNA has been permanently altered to contain the ptpTALECD sequence.

When these genetically modified plants reproduce with themselves through self-fertilization or with nonmodified (wild-type) plants, the next generation of plants inherits nuclear DNA in the normal way, meaning genes are mixed and matched between the ovules and pollen. Some seeds inherit the ptpTALECD sequence and other seeds do not.

However, plants always inherit their chloroplasts whole and intact through their "mothers," the ovules. So regardless of what nuclear DNA the next generation of plants inherits, if their female parent plant had modified chloroplasts, the next generation will always inherit modified chloroplasts.

Researchers then search the offspring to find plants that did not inherit edited nuclear DNA, but did inherit modified chloroplasts. These members of the second generation of plants and any of their future offspring can be considered non-GMO end products because their nuclear DNA contains none of the ptpTALECDs' genetic engineering machinery.

Legal definitions vary, but broadly speaking, countries either assess the end product or the process when deciding to label an organism as a GMO. By end-product definitions used in Japan and the U.S., plants produced with this technique are not GMOs. However, the same plants are GMOs under process based-definitions used in the European Union.

So far, Arimura's team proved their system works by editing three chloroplast genes and observing the expected effects in the offspring plants.

"Chloroplast DNA encodes less than 1% of the total genetic material in a plant, but it has a very important effect on photosynthesis, and therefore the health of the plant. Hopefully, this method will be useful in fundamental research and applied agriculture," said Arimura.

Researchers are optimistic that the fact that none of the genetic engineering tools are inherited by future generations and that the method only makes point mutations will ensure that the method will be used to breed better crops that are accepted by farmers and consumers.

INFORMATION:

Research Publication

Issei Nakazato, Miki Okuno, Hiroshi Yamamoto, Yoshiko Tamura, Takehiko Itoh, Toshiharu Shikanai, Hideki Takanashi, Nobuhiro Tsutsumi, Shin-ichi Arimura. 1 July 2021. Targeted base editing in the plastid genome of Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature Plants. DOI: 10.1038/s41477-021-00954-6

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41477-021-00954-6

Related Links

Laboratory of Plant Molecular Genetics (Japanese only): http://park.itc.u-tokyo.ac.jp/pmg/index.html

Department of Agricultural and Environmental Biology: http://www.ab.a.u-tokyo.ac.jp/aeb/index-e.html

Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences: https://www.a.u-tokyo.ac.jp/english/

Research Contact

Associate Professor Shin-ichi Arimura

Laboratory of Plant Molecular Genetics, Department of Agricultural and Environmental Biology, Graduate School of Agricultural and Life Sciences, The University of Tokyo, 1-1-1 Yayoi, Bunkyo-ku,

Tokyo, 113-8657

Tel: +81-03-5841-5075

Email: arimura@g.ecc.u-tokyo.ac.jp

Press Officer Contact

Ms. Caitlin Devor

Division for Strategic Public Relations, The University of Tokyo, 7-3-1 Hongo, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo 133-8654, JAPAN

Tel: +81-080-9707-8178

Email: press-releases.adm@gs.mail.u-tokyo.ac.jp

About the University of Tokyo

The University of Tokyo is Japan's leading university and one of the world's top research universities. The vast research output of some 6,000 researchers is published in the world's top journals across the arts and sciences. Our vibrant student body of around 15,000 undergraduate and 15,000 graduate students includes over 4,000 international students. Find out more at http://www.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/ or follow us on Twitter at @UTokyo_News_en.

Funders

This research was supported partly from the University of Tokyo GAP fund program and from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant Numbers 20H00417, 16H06279, 19H02927 and 19KK0391).