(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH—An international team of researchers led by Carnegie Mellon University's Manojkumar Puthenveedu has discovered the mechanism by which signaling receptors recycle, a critical piece in understanding signaling receptor function. Writing in the journal Cell, the team for the first time describes how a signaling receptor travels back to the cell membrane after it has been activated and internalized.

Signaling receptors live on the cell membrane waiting to be matched with their associated protein ligand. When they meet, the two join together like a lock and key, turning on and off critical functions within the cell. Many of these functions play a role in human health, and each new discovery about how these complex receptors work provides a potential therapeutic target for conditions including heart, lung and inflammatory disease.

After the receptor and ligand unite, they enter the cell packaged in a container called a vesicle, which delivers them to an even larger container inside the cell called an endosome. From the endosome, receptors can take one of three routes: they can travel to the lysosome and be degraded; travel to the Golgi apparatus and be processed; or the receptor can separate from its ligand and recycle back to the cell membrane via a finger-like offshoot called a tubule.

Some receptors, like nutrient receptors, are recycled back to the cell membrane very quickly through a continuous and unregulated process called bulk recycling. In the case of signaling receptors, researchers noticed that they seemed to recycle at a slower rate and in a more regulated manner. The signaling receptors took minutes to return to the cell surface, indicating that they might not be following the same bulk pathway as other classes of receptors.

"Nutrient receptors can be recycled very quickly without causing any harm, but uncontrolled recycling of a signaling receptor can have serious consequences. For instance, unrestrained signaling through the receptors for adrenaline has been linked to heart failure," Puthenveedu said. "If we can control how fast these receptors travel back to the surface and sequester them inside the cell, we would potentially have a new class of therapeutic targets."

To begin to determine how signaling receptors recycle, Puthenveedu and colleagues looked at the beta-2 adrenergic receptor (b2AR), the receptor for adrenaline and noradrenaline. The receptor is a member of the G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family, a group of receptors that interact with molecules responsible for cellular communication such as neurotransmitters and hormones. GPCRs are well studied because they play a pivotal role in cells' chemical communication circuits that are responsible for regulating functions critical to health, including circuits involved in heart and lung function, mood, cognition and memory, digestion, and the inflammatory response.

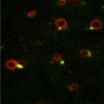

Puthenveedu and colleagues used live cell confocal fluorescence microscopy to label and image b2AR and the tubules by which it recycles, allowing them to visualize what was happening after the signaling receptor was internalized. They found that while the receptors were still being recycled via tubules, much like nutrient receptors, the tubules were not the same. These b2AR tubules emanated from specialized regions, or domains, on the endosome that were marked by a protein network containing actin. These unique domains, which the Carnegie Mellon researchers named Actin-Stabilized Sequence-dependent Recycling Tubule (ASSERT) domains, provided a cellular scaffold. The scaffolding trapped the receptors and slowed the release of the tubule from the endosome, therefore controlling receptor recycling. The researchers believe that they could use these domains, which are essential for signaling receptors to be sorted into the appropriate, slower recycling pathway rather than the faster bulk recycling pathway, as pharmaceutical targets for diseases that result from abnormal cell signaling.

Puthenveedu plans to continue studying receptor recycling in other types of receptors, including opioid receptors. Opiod receptors are the targets of several drugs that are often clinically abused. This research could open up a new area of study in addiction research.

INFORMATION:

This research was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Other authors of this study include Rachel Vistein of Carnegie Mellon; Benjamin Lauffer, Paul Temkin, Peter Carlton, Kurt Thorn, Jack Taunton, Orion D. Weiner, and Mark von Zastrow of the University of California, San Francisco; and Robert Parton of The University of Queensland.

This study was published in the Nov. 24, 2010 issue of Cell.

About Carnegie Mellon: Carnegie Mellon (www.cmu.edu) is a private, internationally ranked research university with programs in areas ranging from science, technology and business, to public policy, the humanities and the fine arts. More than 11,000 students in the university's seven schools and colleges benefit from a small student-to-faculty ratio and an education characterized by its focus on creating and implementing solutions for real problems, interdisciplinary collaboration and innovation. A global university, Carnegie Mellon's main campus in the United States is in Pittsburgh, Pa. It has campuses in California's Silicon Valley and Qatar, and programs in Asia, Australia, Europe and Mexico. The university is in the midst of a $1 billion fundraising campaign, titled "Inspire Innovation: The Campaign for Carnegie Mellon University," which aims to build its endowment, support faculty, students and innovative research, and enhance the physical campus with equipment and facility improvements.

Carnegie Mellon researchers discover mechanism for signaling receptor recycling

Findings could create new class of drug targets

2010-12-23

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

York U study pinpoints part of brain that suppresses instinct

2010-12-23

TORONTO, December 22, 2010 − Research from York University is revealing which regions in the brain "fire up" when we suppress an automatic behaviour such as the urge to look at other people as we enter an elevator.

A York study, published recently in the journal Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, used fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) to track brain activity when study participants looked at an image of a facial expression with a word superimposed on it. Study participants processed the words faster than the facial expressions. However, when the word did ...

A new method is developed for predicting shade improvement after teeth bleaching

2010-12-23

Researchers at the University of Granada have developed a new method for predicting the precise shade that a bleaching treatment will bring about for a patient's teeth. What is innovative about this method is that it allows researchers to successfully predict the outcome of a bleaching treatment, which will have a significant impact on such treatments, which are becoming more frequent.

At present, dental offices routinely employ carbomide peroxide bleaching agents for tooth discoloration. As bleaching treatments have soft side effects –all of them temporary and mild– ...

Eindhoven University builds affordable alternative to mega-laser X-FEL

2010-12-23

Stanford University in the USA has an X-FEL (X-ray Free Electron Laser) with a pricetag of hundreds of millions. It provides images of 'molecules in action', using a kilometer-long electron accelerator. Researchers at Eindhoven University of Technology (TU/e) have developed an alternative that can do many of the same things. However this alternative fits on a tabletop, and costs around half a million euro. That's why the researchers have jokingly called it 'the poor man's X-FEL'.

It's one of the few remaining 'holy grails' of science: a system that allows you to observe ...

Some firms benefit from increased spending despite recession

2010-12-23

During recessions, increased spending on research and development and on advertising can benefit certain types of firms and punish others, according to researchers, who identified the firm types that spend most effectively.

More than 10,000 firm-years of data from publicly listed U.S. firms from 1969 to 2008 -- a period that included seven recessions -- were examined by Gary L. Lilien, Distinguished Research Professor of Management Science, Penn State Smeal College of Business; Raji Srinivasan, University of Texas; and Shrihari Sridhar, Michigan State University.

The ...

Cord blood cell transplantation provides improvement for severely brain-injured child

2010-12-23

Citation: Jozwiak, S.; Habich, A.; Kotulska, K.; Sarnowska, A.; Kropiwnicki, T.; Janowski, M.; Jurkiewicz, E.; Lukomska, B.; Kmiec, T.; Walecki, J.; Roszkowski, M.; Litwin, M.; Oldak, T.; Boruczkowski, D.; Domanska-Janik, K. Intracerebroventricular Transplantation of Cord Blood-Derived Neural Progenitors in a Child With Severe Global Brain Ischemic Injury. Cell Medicine 1(2):71-80; 2010.

The editorial offices for Cell Medicine are at the Center of Excellence for Aging and Brain Repair, College of Medicine, the University of South Florida. Contact, David Eve, PhD. ...

Photons vs. protons for treatment of spinal cord gliomas

2010-12-23

COLUMBUS, Ohio – A study comparing the long-term outcomes of patients with spinal-cord tumors following radiation therapy suggests that certain subsets of patients have better long-term survival. It also suggests that photon-based radiation therapy may result in better survival than proton-beam therapy, even in patients with more favorable characteristics.

This is the first study to report the long-term outcomes of spinal-cord tumor patients treated by modern radiotherapy techniques, the researchers say. Gliomas, which represent most spinal cord tumors, develop in about ...

Which comes first: Exercise-induced asthma or obesity?

2010-12-23

Montreal, December 22, 2010 – Obese people are more likely to report exercise as a trigger for asthma. Of 673 people evaluated in a new study whose results are published in the journal The Physician and Sportsmedicine, 71 percent of participants reported exercise-induced asthma (ETA).

The findings are important, since 2.3 million Canadians are affected by asthma according to Statistics Canada.

ETA affects up to 90 percent of asthma sufferers, says lead author Simon Bacon, a professor at the Concordia Department of Exercise Science and a researcher at the Hôpital du ...

Imagine your future self: Will it help you save money?

2010-12-23

Why do people choose present consumption over their long-term financial interests? A new study in the Journal of Consumer Research finds that consumers have trouble feeling connected to their future selves.

"This willingness to forego money now and wait for future benefits is strongly affected by how connected we feel to our future self, who will ultimately benefit from the resources we save," write authors Daniel M. Bartels (Columbia Business School) and Oleg Urminsky (University of Chicago).

When we think of saving money for the future, the person we think of can ...

Fast sepsis test can save lives

2010-12-23

Although it is the third most frequent cause of death in Germany, blood poisoning is frequently underestimated. In this country, 60,000 persons die every year from some form of sepsis, almost as many as from heart attacks. The Sepsis Nexus of Expertise states that patients arriving at the intensive care ward with blood poisoning only have a 50% chance of surviving. One of the reasons for the high mortality rate is the fact that patients are not correctly treated due to late diagnosis. The doctor and the patient used to have to wait as much as 48 hours for the laboratory ...

Why do risks with human characteristics make powerful consumers feel lucky?

2010-12-23

People who feel powerful are more likely to believe they can beat cancer if it's described in human terms, according to new study in the Journal of Consumer Research.

The study looks at anthropomorphism, or the tendency to attribute humanlike characteristics, intentions, and behavior to nonhuman objects. "The present research shows important downstream consequences of anthropomorphism that go beyond simple liking of products with humanlike physical features," write authors Sara Kim and Ann L. McGill (both University of Chicago).

Previous consumer research has already ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Climate policy support is linked to emotions - study

New method could reveal hidden supermassive black hole binaries

Novel AI model accurately detects placenta accreta in pregnancy before delivery, new research shows

Global Physics Photowalk winners announced

Exercise trains a mouse's brain to build endurance

New-onset nonarteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy and initiators of semaglutide in US veterans with type 2 diabetes

Availability of higher-level neonatal care in rural and urban US hospitals

Researchers identify brain circuit and cells that link prior experiences to appetite

Frog love songs and the sounds of climate change

Hunter-gatherers northwestern Europe adopted farming from migrant women, study reveals

Light-based sensor detects early molecular signs of cancer in the blood

3D MIR technique guides precision treatment of kids’ heart conditions

Which childhood abuse survivors are at elevated risk of depression? New study provides important clues

Plants retain a ‘genetic memory’ of past population crashes, study shows

CPR skills prepare communities to save lives when seconds matter

FAU study finds teen ‘sexting’ surge, warns of sextortion and privacy risks

Chinese Guidelines for Clinical Diagnosis, Treatment, and Management of Cirrhosis (2025)

Insilico Medicine featured in Harvard Business School case on Rentosertib

Towards unlocking the full potential of sodium- and potassium-ion batteries

UC Irvine-led team creates first cell type-specific gene regulatory maps for Alzheimer’s disease

Unraveling the mystery of why some cancer treatments stop working

From polls to public policy: how artificial intelligence is distorting online research

Climate policy must consider cross-border pollution “exchanges” to address inequality and achieve health benefits, research finds

What drives a mysterious sodium pump?

Study reveals new cellular mechanisms that allow the most common chronic cardiac arrhythmia to persist in the heart

Scientists discover new gatekeeper cell in the brain

High blood pressure: trained laypeople improve healthcare in rural Africa

Pitt research reveals protective key that may curb insulin-resistance and prevent diabetes

Queen Mary research results in changes to NHS guidelines

Sleep‑aligned fasting improves key heart and blood‑sugar markers

[Press-News.org] Carnegie Mellon researchers discover mechanism for signaling receptor recyclingFindings could create new class of drug targets