Goldfinder: scientists discover why we can find gold at all

2021-07-05

(Press-News.org) Why are gold deposits found at all? Gold is famously unreactive, and there seems to be little reason why gold should be concentrated, rather than uniformly scattered throughout the Earth's crust. Now an international group of geochemists have discovered why gold is concentrated alongside arsenic, explaining the formation of most gold deposits. This may also explain why many gold miners and others have been at risk from arsenic poisoning. This work is presented at the Goldschmidt conference, after recent publication*.

Gold has been prized for millennia, for its purity and stability. It's also rare enough to retain its value - the World Gold Council estimates that all the gold ever mined in the world would fit into a 20x20x20-meter cube. It is valued for its beauty, but also because it is one of the most inert metals in the whole Periodic Table, it doesn't easily react with other substances. So why should gold come together in sufficient quantity to mine - why are there gold deposits at all?

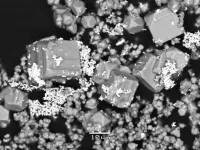

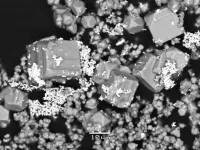

Some gold is found as gold nuggets, the stuff of prospectors' dreams, but an appreciable amount is bound up with minerals. Gold is known to be related to iron- and arsenic-containing minerals, such as pyrite and arsenopyrite. These minerals act sort of like a sponge, and are capable of concentrating gold up to a million times more than is found elsewhere in nature, such as in the hot spring waters that transport the gold. This gold becomes chemically bound in these minerals, so it is invisible to the naked eye.

The scientific team studied the action of the gold-concentrating minerals using the intense X-rays beam produced by the European Synchrotron (ESRF) at Grenoble in France, which can probe the chemical bonds between the mineral and gold.

They found that when the mineral is enriched with arsenic, gold can enter the mineral structural sites by directly binding to arsenic (forming, chemically speaking, Au(2+) and As(1-) bonds), which allows gold to be stabilised in the mineral. However, when the arsenic concentration is low, gold doesn't enter the mineral structure but only forms weak gold-sulfur bonds with the mineral surface.

Lead researcher, Dr. Gleb Pokrovski, Directeur de Recherche at CNRS, GET-CNRS-University of Toulouse Paul Sabatier said:

"Our results show that arsenic drives the concentration of gold. This arsenic-driven gold pump explains how these iron sulfides can massively capture and then release gold, so controlling ore deposit formation and distribution. In practical terms, it means that it will make it easier to find new sources of gold and other precious metals, which bind to arsenic-containing iron sulfides. It may also open the door to controlling the chemical reactions, and if we can improve gold processing, we can recover more gold".

The new model identifies just why gold tends to be found with arsenic. Dr Pokrovski continued:

"It has been known for centuries that gold is found with arsenic, and this has caused severe health problems for gold miners. Now we know what happens at an atomic level, we can begin to see if there's anything we can do to prevent this".

The noxious link between arsenic and gold is well-known in France and elsewhere in the world, including at the Salsigne mine near Carcassonne. This was one of Western Europe's largest gold mines, and the world's largest arsenic producer at one time. It closed in 2004, but the environmental consequences of the arsenic pollution still persist in the region.

Dr. Jeffrey Hedenquist, University of Ottawa, commented that "Geologists as well as prospectors have long known that gold can be associated with arsenic-rich minerals, and over the past few decades others have quantified this association. The findings of Dr. Pokrovski and his team now help to explain why we see this association, caused by an atomic-scale attraction between gold and arsenic, with this marriage arranged by the structure of certain minerals."

INFORMATION:

This is an independent comment, Dr Hedenquist was not involved in this work.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-05

Scientists have reconstructed the Eastern Mediterranean silver trade, over a period including the traditional dates of the Trojan War, the founding of Rome, and the destruction of Solomon's Temple in Jerusalem. The team of French, Israeli and Australian scientists and numismatists found geochemical evidence for pre-coinage silver trade continuing throughout the Mediterranean during the Late Bronze and Iron Age periods, with the supply slowing only occasionally. Silver was sourced from the whole north-eastern Mediterranean, and as far away as the Iberian ...

2021-07-04

Scientists have found an unexplained cache of fossilised shark teeth in an area where there should be none - in a 2900 year old site in the City of David in Jerusalem. This is at least 80 km from where these fossils would be expected to be found. There is no conclusive proof of why the cache was assembled, but it may be that the 80 million-year-old teeth were part of a collection, dating from just after the death of King Solomon*. The same team has now unearthed similar unexplained finds in other parts of ancient Judea.

Presenting the work at the Goldschmidt Conference, lead researcher, Dr. Thomas Tuetken (University of Mainz, Institute of Geosciences) said:

"These fossils are not in their original setting, so they have been moved. They were probably valuable to someone; ...

2021-07-03

Tokyo, Japan - Researchers from Tokyo Metropolitan University have used high power impulse magnetron scattering (HiPIMS) to create thin films of tungsten with unprecedentedly low levels of film stress. By optimizing the timing of a "substrate bias pulse" with microsecond precision, they minimized impurities and defects to form crystalline films with stresses as low as 0.03 GPa, similar to those achieved through annealing. Their work promises efficient pathways for creating metallic films for the electronics industry.

Modern electronics relies on the intricate, nanoscale deposition of thin metallic films onto surfaces. This is easier said than done; unless done right, "film stresses" arising from the microscopic internal structure of the film ...

2021-07-02

In recent years, immunotherapy has revolutionised the field of cancer treatment. However, inflammatory reactions in healthy tissues frequently trigger side effects that can be serious and lead to the permanent discontinuation of treatment. This toxicity is still poorly understood and is a major obstacle to the use of immunotherapy. Scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, and Harvard Medical School, United States, have succeeded in establishing the differences between deleterious immune reactions and those targeting tumour cells that are sought after. It appears that while the immune mechanisms are similar, the cell ...

2021-07-02

It is the membrane of cancer cells that is at the focus of the new research now showing a completely new way in which cancer cells can repair the damage that can otherwise kill them.

In both normal cells and cancer cells, the cell membrane acts as the skin of the cells. And damage to the membrane can be life threatening. The interior of cells is fluid, and if a hole is made in the membrane, the cell simply floats out and dies - a bit like a hole in a water balloon.

Therefore, damage to the cell membrane must be repaired quickly, and now research from a team of Danish researchers shows that cancer cells use a ...

2021-07-02

Fast facts:

Nanobodies have been shown to inhibit the dysfunction of key proteins involved with various diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, psoriasis, B-cell lymphoma, and breast cancer

Understanding the structure of a nanobody helps to better understand its disease-fighting potential

Typically, the protein structure is determined from solid samples. Researchers at NYUAD used a liquid state technique to determine protein structure.

Abu Dhabi, UAE: For the first time in the UAE, researchers at NYU Abu Dhabi have used ...

2021-07-02

For decades, people have wondered why pelagic red crabs--also called tuna crabs--sometimes wash ashore in the millions on the West Coast of the United States. New research shows that atypical currents, rather than abnormal temperatures, likely bring them up from their home range off Baja California.

Alongside the discovery, the scientists also created a seawater flow index that could help researchers and managers detect abnormal current years.

The new study, published July 1 in Limnology and Oceanography, began after lead author Megan Cimino biked past a pelagic red crab stranding on her way to her office in Monterey ...

2021-07-02

East Hanover, NJ. July 2, 2021. Among wheelchair users with spinal cord injury 42 percent reported adverse consequences related to needing wheelchair repair, according to a team of experts in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. The research team, comprised of investigators from the Spinal Cord Injury Model System, determined that this ongoing problem requires action such as higher standards of wheelchair performance, access to faster repair service, and enhanced user training on wheelchair maintenance and repair.

The article, "Factors Influencing Incidence of Wheelchair Repairs and Consequences Among Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury" (doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.01.094) was published online in ...

2021-07-02

BOSTON -- Gaurav Gaiha, MD, DPhil, a member of the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard, studies HIV, one of the fastest-mutating viruses known to humankind. But HIV's ability to mutate isn't unique among RNA viruses -- most viruses develop mutations, or changes in their genetic code, over time. If a virus is disease-causing, the right mutation can allow the virus to escape the immune response by changing the viral pieces the immune system uses to recognize the virus as a threat, pieces scientists call epitopes.

To combat HIV's high rate of mutation, Gaiha and Elizabeth Rossin, MD, PhD, a Retina Fellow at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, a member of Mass General ...

2021-07-02

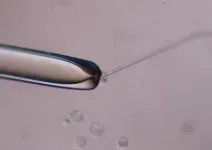

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- A year after University at Buffalo scientists demonstrated that it was possible to produce millions of mature human cells in a mouse embryo, they have published a detailed description of the method so that other laboratories can do it, too.

The ability to produce millions of mature human cells in a living organism, called a chimera, which contains the cells of two species, is critical if the ultimate promise of stem cells to treat or cure human disease is to be realized. But to produce those mature cells, human primed stem cells must be converted back into an earlier, less developed naive state so ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Goldfinder: scientists discover why we can find gold at all