(Press-News.org) For decades, people have wondered why pelagic red crabs--also called tuna crabs--sometimes wash ashore in the millions on the West Coast of the United States. New research shows that atypical currents, rather than abnormal temperatures, likely bring them up from their home range off Baja California.

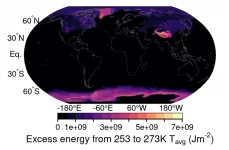

Alongside the discovery, the scientists also created a seawater flow index that could help researchers and managers detect abnormal current years.

The new study, published July 1 in Limnology and Oceanography, began after lead author Megan Cimino biked past a pelagic red crab stranding on her way to her office in Monterey in 2018. Cimino, a biological oceanographer at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and UC Santa Cruz through the Institute of Marine Sciences Fisheries Collaborative Program, had witnessed a different stranding near where she grew up in Southern California a few years prior.

"At that time, I had no clue what a red crab was, what was going on, why they would be there," she said. "But it was very clear something different was going on in the ocean--something unusual."

She brought the question to her colleagues, and the lab decided to dive into the mechanism behind the seemingly random appearances.

The group spent months compiling data about the crabs and their recorded range. They scoured oceanographic research surveys, video data from remotely operated vehicles, citizen science programs, and even online media, such as Twitter.

Integrating the different data types proved challenging, but eventually the team had a clear idea of the species' range and strandings from 1950 to 2019.

Comparing these data with ocean conditions like temperature and current movements, the scientists found that the appearance of red crabs outside of their normal range correlated with the amount of seawater flowing from Baja California to central California. The finding supports strong currents as the key indicator for the presence of the crabs over the other major hypothesis--that warm water brought by marine heatwaves and El Niño events causes the appearances.

To study the currents, the researchers used a regional ocean model of the California Current System, developed by researchers in the UC Santa Cruz ocean modeling group.

"What you're doing is putting a tracer--you could think of it like a dye--into a particular part of the ocean and then running the model backwards in time to see where that came from," said Michael Jacox, a physical oceanographer with dual affiliation with NOAA and UC Santa Cruz.

Based on those tracer experiments, the team created the "southern source water index" (SSWI), which shows how much water off the central California coast comes from south of the U.S.-Mexico border.

"It's that pathway of water that brings up some of these unusual species," said Ryan Rykaczewski, a fisheries oceanographer at NOAA and the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa. "It's not just the pelagic red crabs, even though those might be the most conspicuous species that we see on the coast."

The red crabs draw the public's interest and serve as an important food source for lots of other species. These factors made them a good study subject, but they're not the only thing brought up by currents. They represent a larger phenomenon that researchers can use the SSWI to better understand.

"The index could be used as a kind of early warning system about what the ocean state is that year and whether we're going to expect southern species in northern regions," said Cimino. "That can help us plan and manage and give expectations for bycatch or different fisheries."

As climate change increases variability in ocean conditions, the locations of species will begin to shift. Knowing where to look for particular organisms helps researchers make more accurate observations and population estimates.

"We can go back and look at that source water index and use that perhaps as a predictive tool of how the composition of coastal species is going to change," said Rykaczewski. "And that might help us with ecosystem management."

The way currents shift is an often-overlooked piece of the puzzle when it comes to understanding climate change. Scientists are now in the process of testing whether the southern source water index is sensitive to it.

"We think a lot about the changes in things like temperature and oxygen, but changes in the contribution of waters from different locations in the broader North Pacific is also really important for understanding climate change," said Rykaczewski.

The movement of pelagic red crabs provides just one example of the practical applications of such studies.

"I think it's really, really important that when we think about climate change, we don't just think about 'warm temperature equals some response', and we really try to dig into the mechanisms," said Jacox.

With the case study of red crabs and the creation of the southern source water index, researchers now have another tool for doing just that.

INFORMATION:

In addition to quoted researchers, coauthors include Steven Bograd, Stephanie Brodie, Gemma Carroll and Elliot Hazen at NOAA and UC Santa Cruz as well as Bertha Lavaniegos at the Centro de Investigación Cientifica y Educación Superior de Ensenada in Baja California, Mark Morales at UC Santa Cruz and Erin Satterthwaite at NOAA, UC Santa Barbara and Colorado State University.

East Hanover, NJ. July 2, 2021. Among wheelchair users with spinal cord injury 42 percent reported adverse consequences related to needing wheelchair repair, according to a team of experts in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. The research team, comprised of investigators from the Spinal Cord Injury Model System, determined that this ongoing problem requires action such as higher standards of wheelchair performance, access to faster repair service, and enhanced user training on wheelchair maintenance and repair.

The article, "Factors Influencing Incidence of Wheelchair Repairs and Consequences Among Individuals with Spinal Cord Injury" (doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2021.01.094) was published online in ...

BOSTON -- Gaurav Gaiha, MD, DPhil, a member of the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard, studies HIV, one of the fastest-mutating viruses known to humankind. But HIV's ability to mutate isn't unique among RNA viruses -- most viruses develop mutations, or changes in their genetic code, over time. If a virus is disease-causing, the right mutation can allow the virus to escape the immune response by changing the viral pieces the immune system uses to recognize the virus as a threat, pieces scientists call epitopes.

To combat HIV's high rate of mutation, Gaiha and Elizabeth Rossin, MD, PhD, a Retina Fellow at Massachusetts Eye and Ear, a member of Mass General ...

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- A year after University at Buffalo scientists demonstrated that it was possible to produce millions of mature human cells in a mouse embryo, they have published a detailed description of the method so that other laboratories can do it, too.

The ability to produce millions of mature human cells in a living organism, called a chimera, which contains the cells of two species, is critical if the ultimate promise of stem cells to treat or cure human disease is to be realized. But to produce those mature cells, human primed stem cells must be converted back into an earlier, less developed naive state so ...

When environmental physicist Kira Rehfeld, from Heidelberg University, visited Antarctica for her research, she was struck by the intense light there. "It's always light in summer. This solar radiation could actually be used to supply the research infrastructure with energy", she observes. However, generators, engines, and heaters in these remote regions have mostly been powered until now by fossil fuels delivered by ship, such as petroleum or petrol, which cause global warming. Besides the high associated economic costs, pollution from even the smallest spills is also a major problem threatening the especially sensitive ...

July 2, 2021 - For health care organizations looking to improve performance and patient experiences, implementing data-driven solutions can be effective when focusing on addressing health equity and reducing patient length of stay. These topics are explored in selected member-submitted abstracts from the 2020 Vizient® Connections Education Summit that appear in a special supplement to the July/August 2021 issue of the American Journal of Medical Quality, the official journal of the American College of Medical Quality (ACMQ).

Interventions for addressing health equity

To help health care organizations address ...

GAINESVILLE, Fla. --- Archaeologists have unearthed a END ...

MANHATTAN, KANSAS -- Research led by Kansas State University's Suprem Das, assistant professor of industrial and manufacturing systems engineering, in collaboration with Christopher Sorensen, university distinguished professor of physics, shows potential ways to manufacture graphene-based nano-inks for additive manufacturing of supercapacitors in the form of flexible and printable electronics.

As researchers around the world study the potential replacement of batteries by supercapacitors, an energy device that can charge and discharge very fast -- within few tens of seconds -- the team led by Das has an alternate prediction. The team's work could be adapted to integrate them to overcome ...

A huge global network of researchers is working together to take the pulse of our global tropical forests.

ForestPlots.net, which is co-ordinated from the University of Leeds, brings together more than 2,500 scientists who have examined millions of trees to explore the effect of climate change on forests and biodiversity.

A new research paper published in Biological Conservation explains the origins of the network, and how the power of collaboration is transforming forest research in Africa, South America and Asia.

The paper includes 551 researchers and outlines 25 years of discovery in the carbon, biodiversity and dynamics of tropical forests.

Professor Oliver Phillips, of Leeds' School of Geography, said "Our new paper shows how we are linking students, botanists, ...

MANHATTAN, KANSAS -- A recent study by Kansas State University virologists demonstrates successful postinfection treatment for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

College of Veterinary Medicine researchers Yunjeong Kim and Kyeong-Ok "KC" Chang published the study in the prestigious journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, or PNAS. They found that animal models infected with SARS-CoV-2 and treated with a deuterated protease inhibitor had significantly increased survival and decreased lung viral load.

The results suggest that postinfection treatment with inhibitors of proteases that are essential for viral replication may be an effective treatment against SARS-CoV-2. ...

How on Earth?

It has puzzled scientists for years whether and how bacteria, that live from dissolved organic matter in marine waters, can carry out N2 fixation. It was assumed that the high levels of oxygen combined with the low amount of dissolved organic matter in the marine water column would prevent the anaerobic and energy consuming N2 fixation.

Already in the 1980s it was suggested that aggregates, so-called "marine snow particles", could possibly be suitable sites for N2 fixation, but this was never proven.

Until now..

In a new study, researchers from the University of Copenhagen demonstrate, by use of mathematical models, ...