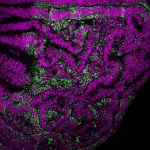

(Press-News.org) Chromosomal instability is a feature of solid tumours such as carcinoma. Likewise, cellular senescence is a process that is highly related to cellular ageing and its link to cancer is becoming increasingly clear. Scientists led by ICREA researcher Dr. Marco Milán at IRB Barcelona have revealed the link between chromosomal instability and cellular senescence.

"Chromosomal instability and senescence are two characteristics common to most tumours, and yet it was not known how one related to the other. Our studies indicate that senescence may be one of the intermediate links between chromosomal alterations and cancer," says Dr. Milan, head of the Development and Growth Control laboratory at IRB Barcelona.

"The behaviour we saw in cells with chromosomal instability made us think that they could be senescent cells and indeed that was the case!" says Dr. Jery Joy, first author of the article published in Developmental Cell.

The study has been conducted on the fly Drosophila, an animal model commonly used in biomedicine, and the mechanisms described may help to understand the contribution of chromosomal instability and senescence to cancer, and facilitate the identification of possible therapeutic targets.

Reversing the effects of chromosomal instability

The researchers from the Development and Growth Control lab have shown that, in an epithelial tissue with high levels of chromosomal instability, those cells with an altered balance of chromosome number detach from their neighbouring cells and enter senescence. Senescent cells are characterised by a permanently halted cell cycle and by the secretion of a large number of proteins. This abnormal secretion of proteins alters the surrounding tissue, alerting the immune system and causing inflammation.

If the senescent cells are not eliminated by the body immediately, they promote abnormal growth of the surrounding tissue, leading to malignant tumours. "If we identify the mechanisms by which we can lower the number of senescent cells, then we will be able to reduce the growth of these tumours," says Dr. Milan. "In fact, this study shows that this is possible, at least in Drosophila," says Dr. Joy.

Cells with an unbalanced number of chromosomes accumulate a high number of aberrant mitochondria and, therefore, a high level of oxidative stress, which in turn activates the JNK signalling pathway, triggering entry into senescence. "We have shown that reducing this high anomalous number of mitochondria, or regulating the oxidative stress that they induce, is sufficient to decrease the number of senescent cells and the negative effects of chromosomal instability," reiterates Dr. Joy.

These findings open new avenues of research to find therapeutic targets and reduce senescence levels caused by chromosomal instability in solid tumours.

Extrapolating from the fly to mammals

The vinegar fly, Drosophila melanogaster, is a widely used in biomedicine. It is a valuable animal model in cancer research because of its short life cycle, the availability of a large number of genetic tools, and the presence of the same genes as in humans, but with a lower level of redundancy.

In fact, experiments designed to dissect the causal relationship between cellular behaviour or characteristics in human tumours, such as chromosomal instability and senescence, are more easily analysed in this model organism.

Future laboratory work will continue to dissect the molecular mechanisms responsible for cellular behaviours found in solid tumours of epithelial origin produced by the mere induction of chromosomal instability. "The more we understand the biology of a tissue subjected to chromosomal instability and the molecular mechanisms responsible for the cellular behaviours that emerge and give rise to malignant tumours, the greater our chances of designing effective therapies and reducing the growth and malignancy of human carcinomas," concludes Dr. Milan.

INFORMATION:

This work was financed by the Ministry of Science and Innovation and the ERDF.

(Boston)--During neuropsychological assessments, participants complete tasks designed to study memory and thinking. Based on their performance, the participants receive a score that researchers use to evaluate how well specific domains of their cognition are functioning.

Consider, though, two participants who achieve the same score on one of these paper-and-pencil neuropsychological tests. One took 60 seconds to complete the task and was writing the entire time; the other spent three minutes, and alternated between writing answers and staring off into space. If researchers ...

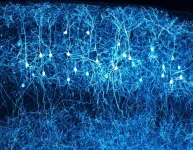

BOSTON -- As we age, our brains typically undergo a slow process of atrophy, causing less robust communication between various brain regions, which leads to declining memory and other cognitive functions. But a rare group of older individuals called "superagers" have been shown to learn and recall novel information as well as a 25-year-old. Investigators from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have now identified the brain activity that underlies superagers' superior memory. "This is the first time we have images of the function of superagers' brains as they actively learn and remember new information," says Alexandra Touroutoglou, PhD, director of Imaging ...

Scientists at the University of Leeds have developed an approach that could help in the design of a new generation of synthetic biomaterials made from proteins.

The biomaterials could eventually have applications in joint repair or wound healing as well as other fields of healthcare and food production.

But one of the fundamental challenges is to control and fine tune the way protein building blocks assemble into complex protein networks that form the basis of biomaterials.

Scientists at Leeds are investigating how changes to the structure and mechanics of individual protein building blocks - changes at the nanoscale - can alter the structure and mechanics of the biomaterial ...

Two model studies document the probability of climate tipping in Earth subsystems. The findings support the urgency of restricting CO2 emissions as abrupt climate changes might be less predictable and more widespread in the climate system than anticipated. The work is part of the European TiPES project, coordinated by the University of Copenhagen, Denmark but was conducted by Professor Michael Ghil, Ecole Normale Supérieure, Paris, France and coauthours from The Royal Meteorological Institute of Belgium and Parthenope University of Naples, Italy.

Tipping could be imminent

It is often assumed climate change will proceed gradually as we increase the amounts of CO2 in ...

Streptococcus pneumoniae is a major human pathogen and a leading cause of several infectious diseases including pneumonia, the third-leading cause of death in Portugal. In Europe, S. pneumoniae is the most common cause of community-acquired bacterial pneumonia in adults. Still, very little is known about its colonization within this age group. A team of researchers from ITQB NOVA has now taken a crucial step to clarify the dynamics of carriage of this bacterium in adults.

This bacterium, also known as pneumococcus, can asymptomatically colonize the human upper respiratory tract. Colonization not only precedes diseases but is also essential for transmission. Even ...

In 2011, scientists confirmed a suspicion: There was a split in the local cosmos. Samples of the solar wind brought back to Earth by the Genesis mission definitively determined oxygen isotopes in the sun differ from those found on Earth, the moon and the other planets and satellites in the solar system.

Early in the solar system's history, material that would later coalesce into planets had been hit with a hefty dose of ultraviolet light, which can explain this difference. Where did it come from? Two theories emerged: Either the ultraviolet light came from our then-young sun, or it came from a large nearby star in the sun's stellar nursery.

Now, researchers from the lab of Ryan Ogliore, assistant professor of physics in Arts ...

The neocortex is a layered structure of the brain in which neurons are arranged parallel to each other. This organization is critical for healthy brain function. A team of researchers from Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin have uncovered two key processes that direct this organization. Reporting in Science Advances*, the researchers identify one crucial factor which ensures the timely movement of neurons into their destined layer and, subsequently, their final parallel orientation within this space.

The neocortex is the outer region of the brain. It is responsible for cognitive functions such as language, decision-making, and ...

A research team, led by Professor Guntae Kim in the School of Energy and Chemical Engineering at UNIST has introduced an innovative way to quantify proton kinetic properties of triple (H+/O2?/e?) conducting oxides (TCOs) being a significant indicator for characterizing the electrochemical behavior of proton and the mechanism of electrode reactions.

Layered perovskites have recently received much attention as they have been regarded as promising cathode materials for protonic ceramic fuel cells (PCFCs) that use proton conducting oxide (PCO) as an electrolyte. Therefore, quantitative characterization of the proton kinetics in TCO can be an important indicator providing a scientific ...

Psychologists from UNSW Sydney have developed a new face identification ability test that will help find facial recognition experts for a variety of police and government agencies, including contract tracing.

The Glasgow Face Matching Test 2 [GFMT2] targets high-performing facial recognition individuals known as super-recognisers, who have an extraordinary ability to memorise and recall faces.

The type of professional roles that involve face identification and that could benefit from the test include visa processors, passport issuers, border control officers, ...

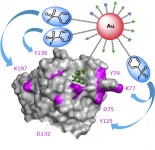

Cells play a precise game of telephone, sending messages to each other that trigger actions further on. With clear signaling, the cells achieve their goals. In disease, however, the signals break up and result in confused messaging and unintended consequences. To help parse out these signals and how they function in health -- and go awry in disease -- scientists tag proteins with labels they can follow as the proteins interact with the molecular world around them.

The challenge is figuring out which proteins to label in the first place. Now, a team led by researchers from Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (TUAT) has developed a new approach to identifying and tagging the specific proteins. They published their results on June 1 in Angewandte ...