Researchers use multivalent gold nanoparticles to develop efficient molecular probe

2021-07-06

(Press-News.org) Cells play a precise game of telephone, sending messages to each other that trigger actions further on. With clear signaling, the cells achieve their goals. In disease, however, the signals break up and result in confused messaging and unintended consequences. To help parse out these signals and how they function in health -- and go awry in disease -- scientists tag proteins with labels they can follow as the proteins interact with the molecular world around them.

The challenge is figuring out which proteins to label in the first place. Now, a team led by researchers from Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (TUAT) has developed a new approach to identifying and tagging the specific proteins. They published their results on June 1 in Angewandte Chemie, a journal of the German Chemical Society.

"We are interested in exploring protein receptors of certain carbohydrate molecules that are involved in mediating cell signaling, particularly in cancer cells," said paper author Kaori Sakurai, associate professor in the Department of Biotechnology and Life Science at TUAT.

The carbohydrate molecules, called ligands, are typically expressed on the surface of cells and are known to dynamically form complexes with protein receptors to coordinate complicated cellular functions. However, Sakurai said, the proteins responsible for binding the carbohydrates have been difficult to identify because they bond so weakly with the molecules.

The researchers designed a new type of carbohydrate probe that would not only link to the molecules, but tightly bind to them.

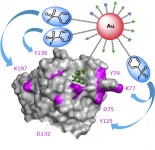

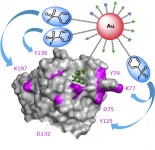

"We used gold nanoparticles as a scaffold to attach both carbohydrate ligands and electrophiles -- a chemical that loves to react with other molecules -- in a multivalent fashion," Sakurai said. "This way, we were able to greatly increase binding affinity and reaction efficiency toward carbohydrate-binding proteins."

The researchers applied the designed probes to cell lysate, a fluid containing the innards of broken-apart cells.

"The probes quickly found the target carbohydrate-binding proteins, triggering the electrophilic groups to react with electron-donating amino acid residues on nearby proteins," Sakurai said. "This resulted in proteins firmly cross-linked to the gold nanoparticles' surface, making it easy to subsequently analyze their identities."

The team evaluated several electrophilic groups to identify the most efficient type for labeling their target proteins.

"We found that a particular electrophilic group called aryl sulfonyl fluoride is best suited for affinity labeling of carbohydrate-binding proteins," said co-author Nanako Suto, a graduate student in the Department of Biotechnology and Life Science of TUAT. "However, they have rarely been used to identify target proteins, presumably because they would non-selectively react with various other, undesired proteins."

However, the scale of aryl sulfonyl fluoride use appears to mitigate the issue.

"The non-selectivity isn't a problem if aryl sulfonyl fluoride is used at very low concentrations, at the range of the nanoscale," said co-author Shione Kamoshita, also a graduate student in the Department of Biotechnology and Life Science, TUAT.

The gold nanoparticle scaffolding displays many copies of the electrophilic group, which keeps aryl sulfonyl fluoride's local concentration high on the nanoparticle surface but restrains them from the general cell system and reacting to undesired proteins. With the high concentration at the nano-level, some copies of electrophilic groups can efficiently react with target proteins.

"Through this process, we were able to achieve highly efficient and selective affinity labeling of carbohydrate-binding proteins in cell lysate," Sakurai said. "We will apply the new method in target identification of several cancer-related carbohydrate ligands and investigate their function in cancer development. In parallel, we aim to explore the general utility of this new probe design for various other bioactive small molecules, so that we can accelerate the elucidation of their mechanisms."

INFORMATION:

Dr. Shoichi Hosoya, Institute of Research, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, also contributed to this paper.

The Japan Society for the Promotion of Science supported this research.

For more information about the Sakurai laboratory, please visit http://web.tuat.ac.jp/~sakurai/

Original publication:

"Exploration of the reactivity of multivalent electrophiles for affinity labeling: sulfonyl fluoride as a highly efficient and selective label"

Nanako Suto, Shione Kamoshita, Shoichi Hosoya and Kaori Sakurai

Angewandte Chemie International Edition

https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.202104347

About Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology (TUAT):

TUAT is a distinguished university in Japan dedicated to science and technology. TUAT focuses on agriculture and engineering that form the foundation of industry, and promotes education and research fields that incorporate them. Boasting a history of over 140 years since our founding in 1874, TUAT continues to boldly take on new challenges and steadily promote fields. With high ethics, TUAT fulfills social responsibility in the capacity of transmitting science and technology information towards the construction of a sustainable society where both human beings and nature can thrive in a symbiotic relationship. For more information, please visit http://www.tuat.ac.jp/en/.

Contact:

Kaori Sakurai, Ph.D.

Associate Professor

Department of Biotechnology and Life Science

Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology, Japan

sakuraik@cc.tuat.ac.jp

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-06

AUSTIN, Texas -- A diagnostic tool called the MasSpec Pen has been tested for the first time in pancreatic cancer patients during surgery. The device is shown to accurately identify tissues and surgical margins directly in patients and differentiate healthy and cancerous tissue from banked pancreas samples. At about 15 seconds per analysis, the method is more than 100 times as fast as the current gold standard diagnostic, Frozen Section Analysis. The ability to accurately identify margins between healthy and cancerous tissue in pancreatic cancer surgeries can give patients the greatest chance of survival.

The results, by a team from ...

2021-07-06

TORONTO, July 6, 2021 - What's stressing out bumblebees? To find out, York University scientists used next-generation sequencing to look deep inside bumblebees for evidence of pesticide exposure, including neonicotinoids, as well as pathogens, and found both.

Using a conservation genomic approach - an emerging field of study that could radically change the way bee health is assessed - the researchers studied Bombus terricola or the yellow-banded bumblebee, a native to North America, in agricultural and non-agricultural areas. This new technique allows scientists to probe for invisible stressors affecting bees.

Like many pollinators, the yellow-banded bumblebee ...

2021-07-06

A collaborative research project between the five First Nations of the Nanwakolas Council of B.C. and Simon Fraser University is contributing to conservation efforts of the iconic western redcedar tree.

New research in the Journal of Ethnobiology highlights concerns about the long-term sustainability of this culturally significant resource. Researchers found that western redcedar trees suitable for traditional carving are generally rare. Some important growth forms, such as large, spectacular trees appropriate for carving community canoes, are nearly extirpated from ...

2021-07-06

WASHINGTON, July 6, 2021 -- Emitted as gases from certain solids or liquids, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) include a variety of chemicals. Many of these chemicals are associated with a range of adverse human health effects, from eye, nose, and throat irritation, to liver, kidney, and central nervous system damage.

The ability to detect VOCs in air samples simply, quickly, and reliably is valuable for several practical applications, from determining indoor air quality to screening patients for illnesses.

In Review of Scientific Instruments, by AIP ...

2021-07-06

Mammals have a poor ability to recover after a spinal cord injury which can result in paralysis. A main reason for this is the formation of a complex scar associated with chronic inflammation that produces a cellular microenvironment that blocks tissue repair. Now, a research team led by Leonor Saude, group leader at Instituto de Medicina Molecular Joao Lobo Antunes (iMM; Portugal) and Professor at Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa, have shown that the administration of drugs that target specific cellular components of this scar, improve functional recovery after injury. The results now published in the scientific journal Cell Reports* set the basis for a new promising therapeutic strategy not ...

2021-07-06

From the bark of a puppy to the patter of rain against the window, our brains receive countless signals every second. Most of the time, we tune out inconsequential cues--the buzz of a fly, the soft rustle of leaves in the tree--and pay attention to important ones--the sound of a car horn, a bang on the door. This allows us to function, navigate and, indeed, survive in the world around us.

The brain's remarkable ability to sift through this ceaseless flow of information is enabled by an intricate neural network made up of billions of synapses, specialized junctions that regulate signal transmission between and ...

2021-07-06

PITTSBURGH, July 6, 2021 - Scientists from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine described a new phenomenon in which the deletion of a single gene involved in liver embryogenesis completely wipes out bile ducts of newborn mice. But despite a major defect in their bile excretion system, those animals don't die immediately after birth. Rather, they survive for up to eight months and remain physically active, if small and yellow-tinted.

Published today in the journal Cell Reports, the finding offers clues as to why some patients with cholestasis--or impaired ...

2021-07-06

What The Study Did: Rates at which patients with type 2 diabetes received diabetes-related health services prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic are compared in this study.

Authors: Ateev Mehrotra, M.D., M.P.H., of Harvard Medical School in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.3047)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, ...

2021-07-06

What The Study Did: COVID-19 vaccine-associated messenger RNA (mRNA) wasn't detected in 13 human milk samples collected after vaccination from seven breastfeeding mothers.

Authors: Stephanie L. Gaw, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1929)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict ...

2021-07-06

What The Study Did: This study in the Lombardy region of Italy examined the association of different health care professional categories and operational units, including in-hospital wards and outpatient facilities, with the seroprevalence of positive IgG antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2 and the likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Authors: Piero Poletti, Ph.D., of the Bruno Kessler Foundation in Trento, Italy, and Marcello Tirani, M.D., Directorate General for Health, Lombardy region, in Milan, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15699)

Editor's Note: The article includes ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Researchers use multivalent gold nanoparticles to develop efficient molecular probe