(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, July 6, 2021 - Scientists from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine described a new phenomenon in which the deletion of a single gene involved in liver embryogenesis completely wipes out bile ducts of newborn mice. But despite a major defect in their bile excretion system, those animals don't die immediately after birth. Rather, they survive for up to eight months and remain physically active, if small and yellow-tinted.

Published today in the journal Cell Reports, the finding offers clues as to why some patients with cholestasis--or impaired bile secretion due to liver injury--seem to fare far better than others with seemingly identical genetic makeup. Researchers think that the key lies in the novel cell-signaling pathway activated as a way of adapting to the liver injury--and, incidentally, that pathway was never studied in the context of adaptation before.

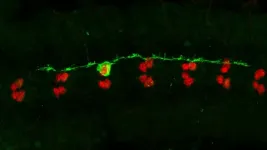

"Our finding was quite serendipitous," admits senior author Satdarshan (Paul) Monga, M.D., professor at Pitt's Department of Medicine. "We discovered that mice with a deletion of an embryonic gene YAP1 in the early precursors of liver cells don't form bile ducts at all. But surprisingly, those animals didn't die--rather, their livers figured out a way to shunt the excess bile into the bloodstream instead of poisoning themselves.

"The liver couldn't care less about other organs, it just wants to live," Monga added.

The liver is vital for our body's survival. It serves more than 500 essential functions a day, acting like a giant synthetic, metabolic and purification plant that clears out toxic chemicals from our bloodstream--from alcohol to excessive amounts of fats, which get broken down by soap-like bile acids in the intestine.

But the bile itself is toxic, too. The bile ducts, which collect secreted bile acids and deliver them to the gut where they help with digestion are important for ensuring that the liver doesn't poison itself. Whenever the bile ducts are injured or malformed as a result of genetic defects, the liver function suffers. For example, children with Alagille syndrome, whose bile ducts are underdeveloped or absent because of mutations in embryonic proteins, develop cholestasis, which might result in liver failure, as well as heart disease and bone abnormalities.

Even more puzzling, the scientists observed a phenotype similar to human Alagille-like syndrome in mice lacking YAP1 gene--a signaling molecule widely present in embryonic cells that give rise to liver cells, or hepatocytes, and cells that make up bile ducts, or cholangiocytes. Those animals, scientists say, look yellow and are very small in size, but otherwise survive despite the complete lack of bile ducts.

Rather than being poisoned by bile, the liver of those mice seemingly adapted to the injury by decreasing bile synthesis, making it less toxic, and shunting it to the bloodstream instead of dumping it into the liver indiscriminately.

This newly discovered innate adaptive mechanism might explain why some patients with liver injury develop symptoms of acute liver toxicity later than others. It also might offer a clue to clinicians about new ways of treating those patients in the future.

"The severity of symptoms in patients with genetic defects in the liver varies dramatically," said first author Laura Molina, Ph.D., medical student at Pitt. "Our research suggests that YAP1 could be an elusive disease modifier that regulates disease outcomes in these patients. We hope that, by studying the functions of YAP1 and promoting the mechanism of adaptation, we can better understand the liver disease and improve existing treatments."

INFORMATION:

Other authors on the manuscript include Junjie Zhu, Ph.D., Qin Li, Ph.D., Tirthadipa Pradhan-Sundd, Ph.D., Yekaterina Krutsenko, B.S., Khaled Sayed, Ph.D., Nathaniel Jenkins, B.S., Ravi Vats, Ph.D., Bharat Bhushan, Ph.D., Sungjin Ko, Ph.D., Shikai Hu, B.S., Minakshi Poddar, M.S., Sucha Singh, B.S., Junyan Tao, Ph.D., Prithu Sundd, Ph.D., Aatur Singhi, M.D., Ph.D., Simon Watkins, Ph.D., Xiaochao Ma, Ph.D., Panayiotis Benos, Ph.D., Andrew Feranchak, M.D., George Michalopoulos, M.D., Ph.D., Kari Nejak-Bowen, M.B.A., Ph.D., Alan Watson, Ph.D., and Aaron Bell, Ph.D., all of Pitt.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants 2T32EB001026-16A1, 1F30DK121393-01A1, 5R01CA204586-05, 1R01DK62277, 1P30DK120531-01 and 2P30CA047904-32). The study was funded in part by the Endowed Chair for Experimental Pathology and the Center for Biological Imaging at the University of Pittsburgh.

To read this release online or share it, visit https://www.upmc.com/media/news/070621-monga-molina-bile-ducts [when embargo lifts].

About the University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences

The University of Pittsburgh Schools of the Health Sciences include the schools of Medicine, Nursing, Dental Medicine, Pharmacy, Health and Rehabilitation Sciences and the Graduate School of Public Health. The schools serve as the academic partner to the UPMC (University of Pittsburgh Medical Center). Together, their combined mission is to train tomorrow's health care specialists and biomedical scientists, engage in groundbreaking research that will advance understanding of the causes and treatments of disease and participate in the delivery of outstanding patient care. Since 1998, Pitt and its affiliated university faculty have ranked among the top 10 educational institutions in grant support from the National Institutes of Health. For additional information about the Schools of the Health Sciences, please visit http://www.health.pitt.edu.

http://www.upmc.com/media

What The Study Did: Rates at which patients with type 2 diabetes received diabetes-related health services prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic are compared in this study.

Authors: Ateev Mehrotra, M.D., M.P.H., of Harvard Medical School in Boston, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.3047)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, ...

What The Study Did: COVID-19 vaccine-associated messenger RNA (mRNA) wasn't detected in 13 human milk samples collected after vaccination from seven breastfeeding mothers.

Authors: Stephanie L. Gaw, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of California, San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.1929)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict ...

What The Study Did: This study in the Lombardy region of Italy examined the association of different health care professional categories and operational units, including in-hospital wards and outpatient facilities, with the seroprevalence of positive IgG antibody tests for SARS-CoV-2 and the likelihood of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Authors: Piero Poletti, Ph.D., of the Bruno Kessler Foundation in Trento, Italy, and Marcello Tirani, M.D., Directorate General for Health, Lombardy region, in Milan, are the corresponding authors.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15699)

Editor's Note: The article includes ...

What The Study Did: This national analysis examined the association between the travel distance to the nearest abortion care facility and abortion rate and the effect of reduced travel distance.

Authors: Kirsten M. J. Thompson, M.P.H., of the University of California, San Francisco, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15530)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional ...

What The Study Did: The amount Medicare pays for common generic prescriptions in Part D was compared with prices available to patients without insurance at Costco.

Authors: Erin Trish, Ph.D., of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2021.3366)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and affiliations, conflict of interest and financial disclosures, and funding and support.

INFORMATION:

Media advisory: The full study is linked ...

Melbourne researchers have identified a way to improve the immune response in the face of severe viral infections.

It is widely known that severe viral infections and cancer cause impairments to the immune system, including to T cells, a process called immune 'exhaustion'. Overcoming immune exhaustion is a major goal for the development of new therapies for cancer or severe viral infections.

A team from the Peter Doherty Institute of Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) led by University of Melbourne's Dr Sarah Gabriel, Dr Daniel Utzschneider and Professor Axel Kallies has been able to identify why immune exhaustion occurs and how this may be overcome.

The team had previously identified that while some T cells ...

Most human cells are able to repair damage by dividing at wounds.

But mature nerve cells (neurons) in our brain are different. If they attempt division, they will likely die - and this is what happens during brain injury, or in conditions such as Alzheimer's Disease (AD). Now new research led by the University of Plymouth has uncovered a pathway that has shed new light on how these divisions may be triggered.

The research, published today in Cell Reports, has focused on intracellular structures called microtubules - which are found in most animal cells, and can be damaged by a build-up of a protein called Tau in the brain during AD.

The study was conducted in fruit flies, with comparison to postmortem brain samples ...

Can you remember the smell of flowers in your grandmother's garden or the tune your grandpa always used to whistle? Some childhood memories are seemingly engrained into your brain. In fact, there are critical periods in which the brain learns and saves profound cognitive routines and memories. The structure responsible for saving them is called the perineuronal net.

This extracellular structure envelops certain neurons, thereby stabilizes existing connections - the synapses - between them and prevents new ones from forming. But what if we could remove the perineuronal net and restore the adaptability of a young brain? The neuroscientist Sandra Siegert and her research group at IST Austria now ...

Dinosaurs were generally huge, but a new study of the unusual alvarezsaurs show that they reduced in size about 100 million years ago when they became specialised ant-eaters.

The new work is led by Zichuan Qin, a PhD student at the University of Bristol and Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. He measured body sizes of dozens of specimens and showed that they ranged in size from 10-70 kg, the size of a large turkey to a small ostrich, for most of their existence and then plummeted rapidly to chicken-sized animals at the same time as they adopted a remarkable ...

An international team of scientists has used high-powered X-rays at the European Synchrotron, the ESRF, to show how an extinct South African 200-million-year-old dinosaur, Heterodontosaurus tucki, breathed. The study is published in eLife on 6 July 2021.

In 2016, scientists from the Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, came to the ESRF, the European Synchrotron in Grenoble, France, the brightest synchrotron light source, for an exceptional study: to scan the complete skeleton of a small, 200-million-year-old plant-eating dinosaur. The dinosaur specimen is the most complete fossil ever discovered of a species known as Heterodontosaurus tucki. The fossil was found in ...