INFORMATION:

The team will now explore this mechanism in preclinical cancer models.

This work was done in collaboration with researchers from the Olivia Newton John Cancer Research Institute and Monash University.

Peer review: Immunity doi.org/10.1016/j.immuni.2021.06.007

Funding: NHMRC, Swiss National Science Foundation, Novartis Foundation for Medical-Biological Research, Leukemia & Lymphoma Society

This study used mouse models

Researchers discover way to improve immune response

2021-07-06

(Press-News.org) Melbourne researchers have identified a way to improve the immune response in the face of severe viral infections.

It is widely known that severe viral infections and cancer cause impairments to the immune system, including to T cells, a process called immune 'exhaustion'. Overcoming immune exhaustion is a major goal for the development of new therapies for cancer or severe viral infections.

A team from the Peter Doherty Institute of Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute) led by University of Melbourne's Dr Sarah Gabriel, Dr Daniel Utzschneider and Professor Axel Kallies has been able to identify why immune exhaustion occurs and how this may be overcome.

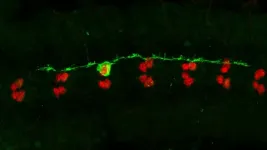

The team had previously identified that while some T cells lost their function and became exhausted within days, others, called Tpex cells, were able to maintain their function for a long period of time.

"This idea that you need to overcome exhaustion and make T cells better is at the heart of immunotherapy," Professor Kallies said.

"While immunotherapy works really well, it is only effective in around 30 per cent of people. By discovering a way to prime T cells differently so they can work efficiently in the long run, we may be able to make immunotherapy more effective in more people."

In their most recent paper published today in Immunity, the team has now identified a mechanism explaining how Tpex cells can maintain their fitness over long periods.

Professor Kallies says that the discovery has the potential to improve the success rate of immunotherapy.

"We found that activity of mTOR, a nutrient sensor that coordinates cellular energy production and expenditure, is reduced in Tpex cells compared to those which were becoming exhausted," Dr Gabriel said.

"What this means is that Tpex cells were able to dampen their activity so they could remain functional longer - it's like going slower to have the endurance to run a marathon instead of a sprint at full speed."

Dr Utzschneider stressed that flicking this switch to the immune system is a balancing act.

"You don't want to dampen the response too much to the point the response becomes ineffective - you don't want to be left walking the race," Dr Utzschneider said.

"The next step was finding the mechanism which was enabling this. We discovered that Tpex cells were exposed to increased amounts of an immunosuppressive molecule, TGF?? early on in an infection. This molecule essentially acts as a brake, reducing the activity of mTOR and thereby dampening the immune response."

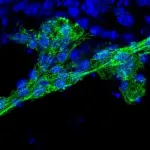

Excitingly, the researchers were able to use this discovery to improve the immune response to severe viral infection.

"When we treated mice with an mTOR inhibitor early, this resulted in a better immune response later during the infection," Dr Gabriel said.

"In addition, mice that had been treated with the mTOR inhibitor responded better to checkpoint inhibition, a therapy widely used in cancer patients."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

New signaling pathway could shed light on damage repair during brain injury

2021-07-06

Most human cells are able to repair damage by dividing at wounds.

But mature nerve cells (neurons) in our brain are different. If they attempt division, they will likely die - and this is what happens during brain injury, or in conditions such as Alzheimer's Disease (AD). Now new research led by the University of Plymouth has uncovered a pathway that has shed new light on how these divisions may be triggered.

The research, published today in Cell Reports, has focused on intracellular structures called microtubules - which are found in most animal cells, and can be damaged by a build-up of a protein called Tau in the brain during AD.

The study was conducted in fruit flies, with comparison to postmortem brain samples ...

The twinkle and the brain

2021-07-06

Can you remember the smell of flowers in your grandmother's garden or the tune your grandpa always used to whistle? Some childhood memories are seemingly engrained into your brain. In fact, there are critical periods in which the brain learns and saves profound cognitive routines and memories. The structure responsible for saving them is called the perineuronal net.

This extracellular structure envelops certain neurons, thereby stabilizes existing connections - the synapses - between them and prevents new ones from forming. But what if we could remove the perineuronal net and restore the adaptability of a young brain? The neuroscientist Sandra Siegert and her research group at IST Austria now ...

Sharp size reduction in dinosaurs that changed diet to termites

2021-07-06

Dinosaurs were generally huge, but a new study of the unusual alvarezsaurs show that they reduced in size about 100 million years ago when they became specialised ant-eaters.

The new work is led by Zichuan Qin, a PhD student at the University of Bristol and Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology in Beijing. He measured body sizes of dozens of specimens and showed that they ranged in size from 10-70 kg, the size of a large turkey to a small ostrich, for most of their existence and then plummeted rapidly to chicken-sized animals at the same time as they adopted a remarkable ...

New fossil sheds light on the evolution of how dinosaurs breathed

2021-07-06

An international team of scientists has used high-powered X-rays at the European Synchrotron, the ESRF, to show how an extinct South African 200-million-year-old dinosaur, Heterodontosaurus tucki, breathed. The study is published in eLife on 6 July 2021.

In 2016, scientists from the Evolutionary Studies Institute at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, came to the ESRF, the European Synchrotron in Grenoble, France, the brightest synchrotron light source, for an exceptional study: to scan the complete skeleton of a small, 200-million-year-old plant-eating dinosaur. The dinosaur specimen is the most complete fossil ever discovered of a species known as Heterodontosaurus tucki. The fossil was found in ...

Dignity support at end of life

2021-07-06

At the end of life, people may have to rely on others for help with showering, dressing and going to the toilet. This loss of privacy and independence can be confronting and difficult.

Now Australian occupational therapy (OT) researchers have interviewed 18 people receiving palliative care about how they feel about losing independence with self-care, specifically their intimate hygiene, as function declines with disease progression.

The study aims to raise awareness of how to provide better care for people at the end of life.

Lead researcher Dr Deidre Morgan, a Flinders University occupational ...

New game-changing zeolite catalysts synthesized

2021-07-06

A research team at POSTECH has uncovered a promising new zeolite, anticipated to be a turning point for the oil refining and petrochemical industries. This research was recently published in the scientific journal Science on July 2, 2021.

The team of researchers led by Suk Bong Hong, a professor in the Division of Environmental Science and Engineering at POSTECH, synthesized two thermally stable three-dimensional (3D) large-pore (12-ring)1 zeolites - PST-32 (POSTECH No. 32) and PST-2, the hypothetical SBS/SBT intergrowth structure2 - by using the "multiple inorganic cation" and the "charge density mismatch" synthetic strategies, respectively. The research team identified their structures by using both powder X-ray diffraction ...

Chemo upsets gut health in cancer patients

2021-07-06

New research in BMC Cancer has shown myelosuppressive chemotherapy destabilises gut microbiome in patients with solid organ cancers.

The study from SAHMRI and Flinders University assessed the gut health of men and women who underwent conventional chemotherapy on cancers, such as breast and lung cancer, without exposure to antibiotics.

"We know that myelosuppressive chemotherapy reduces white blood cell count significantly during the first seven to 10 days of treatment, making the body more vulnerable to infection," says lead author Dr Lito Papanicolas, an infectious diseases expert and clinical microbiologist.

"In this study we focused on how much the individual's microbiome changed over this period, when the ...

Engineered cells successfully treat cardiovascular and pulmonary disease

2021-07-06

Scientists at UC San Francisco have shown that gene-edited cellular therapeutics can be used to successfully treat cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, potentially paving the way for developing less expensive cellular therapies to treat diseases for which there are currently few viable options.

The study, in mice, is the first in the emerging field of regenerative cell therapy to show that products from specially engineered induced pluripotent stem cells called "HIP" cells can successfully be employed to treat major diseases while evading the ...

University of Guam: Less than 10% of transplanted cycads survive long-term in foreign soil

2021-07-06

A 15-year reciprocal transplant study on Guam's native cycad tree, Cycas micronesica, by the Plant Physiology Laboratory at the University of Guam's Western Pacific Tropical Research Center has revealed that acute adaptation to local soil conditions occurs among the tree population and is important in the survival rate of transplanted cycads. The results show that 70% to 100% of cycads that were transplanted in local conditions survived versus less than 10% that were transplanted in foreign conditions. The article describing the study has been published in the peer-reviewed journal Diversity (doi: 10.3390/d13060237).

Transplantation ...

Vertical greenery can act as a stress buffer, NTU Singapore study finds

2021-07-06

Vertical greenery 'planted' on the exterior of buildings may help to buffer people against stress, a Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) study has found.

The benefits of nature on mental health and for wellbeing have long been recognised, and now a team of NTU Singapore psychologists has used Virtual Reality (VR) to examine whether vertical greenery has a stress buffering effect (ability to moderate the detrimental consequences of stress) in an urban environment.

Using VR headsets, 111 participants were asked to walk down a virtual street for five minutes. Participants were randomly assigned to either a street that featured rows of planted greenery (e.g., on balconies, walls, and pillars of buildings), ...