(Press-News.org) Scientists at UC San Francisco have shown that gene-edited cellular therapeutics can be used to successfully treat cardiovascular and pulmonary diseases, potentially paving the way for developing less expensive cellular therapies to treat diseases for which there are currently few viable options.

The study, in mice, is the first in the emerging field of regenerative cell therapy to show that products from specially engineered induced pluripotent stem cells called "HIP" cells can successfully be employed to treat major diseases while evading the immune system. The findings subvert the immune response that is a major cause of transplant failure and poses a barrier to using engineered cells as therapy.

"We showed that immune-engineered HIP cells reliably evade immune rejection in mice with different tissue types, a situation similar to the transplantation between unrelated human individuals. This immune evasion was maintained in diseased tissue and tissue with poor blood supply without the use of any immunosuppressive drugs." said Tobias Deuse, MD, the Julien I.E. Hoffman, M.D. Endowed Chair in Cardiac Surgery and a first author of the study.

Deuse's research is an example of "living therapeutics," an emerging pillar of medicine in which treatments are broadly defined as living human and microbial cells that are selected, modified, or engineered to treat or cure disease.

The study appears in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America).

"Universal Stem Cells" Avoid Immune Detection

The prospects of generating specialized cells in a dish that can be transplanted into patients to treat various diseases are encouraging, the scientists report. However, the immune system would immediately recognize cells that were recovered from another individual and would reject the cells. Hence, some scientists believe that custom cell therapeutics need to be generated from scratch using a blood sample from every individual patient as starting material.

The research group at UCSF followed a different approach, using gene editing to create 'universal stem cells' (named HIP cells) that are not recognized by the immune system and can be used to make "universal cell therapeutics."

The team tested the ability of these cells to treat three major diseases affecting different organ systems: Peripheral artery disease; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency; and heart failure, increasingly a global epidemic with more than 5.7 million patients in the United States alone and some 870,000 new cases annually.

The scientists transplanted specialized, immune-engineered HIP cells into mice with each of these conditions and were able to show that the cell therapeutics could alleviate peripheral artery disease in hindlimbs, prevent the development of lung disease in mice with alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency, and alleviate heart failure in mice after myocardial infarction.

To enhance the translational aspect of this proof-of-concept study, the researchers assessed the treatment's efficacy using standard parameters for human clinical trials focusing on outcome and organ function.

The Promise of an Affordable Option

Deuse, who is also surgical director of the Transcatheter Valve Program and directs Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery, plans to explore the potential of these universal stems cells for treating other endocrine and cardiovascular conditions. He noted that, because of the novelty of the approach, a careful and measured introduction into clinical trials will be crucial. Once more is known about human safety, he said, it will be easier to estimate when treatments using HIP cells might be approved and available for patients.

One of the great benefits of this approach, said Deuse, is that the strategy of immune engineering comes with a reasonable price tag. It would make the manufacturing of universal, high-quality cell therapeutics more cost effective, could allow future treatment of larger patient populations, and facilitate access for patients from underserved communities.

"In order for a therapeutic to have a broad impact, it needs to be affordable," said Deuse. "That's why we focus so much on immune-engineering and the development of universal cells. Once the costs come down, the access for all patients in need increases."

INFORMATION:

Sonja Schrepfer, MD, PhD, a senior author on the paper, is a UCSF professor who has joined Sana Biotechnology, Inc. for the translation of the HIP technology into human therapeutics. She is a pioneer of immune engineering and co-inventor of the HIP cells The other co-senior author of the paper is Lewis L. Lanier, PhD, a UCSF professor of Microbiology and Immunology, and co-leader of the Cancer Immunology & Immunotherapy Program at the UCSF Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center.

About UCSF: The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) is exclusively focused on the health sciences and is dedicated to promoting health worldwide through advanced biomedical research, graduate-level education in the life sciences and health professions, and excellence in patient care. UCSF Health, which serves as UCSF's primary academic medical center, includes top-ranked specialty hospitals and other clinical programs, and has affiliations throughout the Bay Area. UCSF School of Medicine also has a regional campus in Fresno. Learn more at ucsf.edu, or see our Fact Sheet.

Follow UCSF

ucsf.edu | Facebook.com/ucsf | YouTube.com/ucsf

A 15-year reciprocal transplant study on Guam's native cycad tree, Cycas micronesica, by the Plant Physiology Laboratory at the University of Guam's Western Pacific Tropical Research Center has revealed that acute adaptation to local soil conditions occurs among the tree population and is important in the survival rate of transplanted cycads. The results show that 70% to 100% of cycads that were transplanted in local conditions survived versus less than 10% that were transplanted in foreign conditions. The article describing the study has been published in the peer-reviewed journal Diversity (doi: 10.3390/d13060237).

Transplantation ...

Vertical greenery 'planted' on the exterior of buildings may help to buffer people against stress, a Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) study has found.

The benefits of nature on mental health and for wellbeing have long been recognised, and now a team of NTU Singapore psychologists has used Virtual Reality (VR) to examine whether vertical greenery has a stress buffering effect (ability to moderate the detrimental consequences of stress) in an urban environment.

Using VR headsets, 111 participants were asked to walk down a virtual street for five minutes. Participants were randomly assigned to either a street that featured rows of planted greenery (e.g., on balconies, walls, and pillars of buildings), ...

Attention training in young people with autism can lead to significant improvements in academic performance, according to a new study.

Researchers at the University of Birmingham in the UK along with institutions in São Paolo, in Brazil, tested a computer programme designed to train basic attention skills among a group of autistic children aged between eight and 14 years old.

They found participants achieved improvements in maths, reading, writing and overall attention both immediately after undergoing the training and at a three-month follow up assessment. Their results are published in Autism Research.

Lead researcher, Dr Carmel Mevorach, in the University of Birmingham's Centre for Human Brain Health, and School of Psychology, says: "It's ...

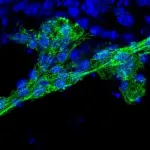

The urgency to remember a dangerous experience requires the brain to make a series of potentially dangerous moves: Neurons and other brain cells snap open their DNA in numerous locations--more than previously realized, according to a new study--to provide quick access to genetic instructions for the mechanisms of memory storage.

The extent of these DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) in multiple key brain regions is surprising and concerning, said study senior author Li-Huei Tsai, Picower Professor of Neuroscience at MIT and director of The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, because while the breaks are routinely repaired, that process may become more flawed and fragile with age. Tsai's lab has shown that lingering DSBs are associated with neurodegeneration ...

Peptide: N-glycanase (NGLY1) is an evolutionarily conserved enzyme for removing N-linked glycans (N-glycans) from glycoproteins and is involved in proteostasis of N-glycoproteins in the cytosol. In 2012, a rare genetic disorder called NGLY1 deficiency was discovered by an exome analysis. Symptoms in patients with NGLY1 deficiency include global developmental delay, hypotonia, hypo/alacrima, movement disorder, scoliosis, abnormal liver, brain functions and peripheral neuropathy. Unfortunately, no therapeutic treatment is currently available to this devastating ...

Researchers from Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) find proteins that bind to and regulate tocopherol-conjugated heteroduplex oligonucleotides during gene silencing

Tokyo, Japan - Gene silencing therapies are used to interfere with, or "silence", the expression of genes that are associated with disorders. Now, a team at TMDU has uncovered some of the cellular mechanisms by which the silencing therapies act in cells.

Antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) therapies use small strands of DNA or RNA that are antisense, or complementary, to the associated gene to interfere with its expression. ASO therapies are already available for some diseases, particularly neurological disorders, but their use is at a very ...

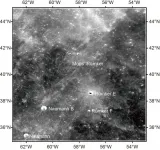

China's lunar exploration project can be divided into three steps: "orbiting", "landing" and "returning". At present, the first two have been completed, and the third step, "return", will be achieved by the CE-5, which is the first sample return satellite of China and is expected to drill at a depth of no less than 2 m and bring back about 2 kg of scientific samples. In June 2017, the landing region of CE-5 lunar probe was selected as the Rümker region, which is located in the northern Oceanus Procellarum on the lunar near side and has a long volcanic history and complex geological composition.

Because the geographical scope of the region is not clearly defined, the extent determined by the researchers is 35°-45°N ...

The change from early years services into formal educational settings has long been considered an integral transition point for young people. Now research from Flinders University now asks, "Is service integration actually important to the children?"

A recent paper, published in Children's Geographies, led by Flinders University PhD Dr Jennifer Fane, who is now based at Capilano University in Canada, actually seems to have little impact on children's experiences of this transition.

The Australian Government has supported the Integrated Early Years Services since 2005, following what is considered best practice policy for supporting children and families. It is considered to constitute services that are connected ...

Tantalising evidence has been uncovered for a mysterious population of "free-floating" planets, planets that may be alone in deep space, unbound to any host star. The results include four new discoveries that are consistent with planets of similar masses to Earth, published today in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

The study, led by Iain McDonald of the University of Manchester, UK, (now based at the Open University, UK) used data obtained in 2016 during the K2 mission phase of NASA's Kepler Space Telescope. During this two-month campaign, Kepler monitored a crowded field of millions ...

Hannah Enders and Dr. Florian Hennicke describe the precise anatomy of these structures of the poplar mushroom in the Journal of Fungi of 19 May 2021.

An edible wild mushroom

One of the organisms attacked by the fungus Cyclocybe parasitica is the Tawa tree (Beilschmiedia tawa), which is relevant to the timber industry in New Zealand. Cyclocybe parasitica is widespread in the Pacific region and has long been known to the Maori, the indigenous people of New Zealand, under the name "Tawaka" as an edible wild mushroom.

Biology student Hannah Elders, supervised by Florian Hennicke at ...