The brain's remarkable ability to sift through this ceaseless flow of information is enabled by an intricate neural network made up of billions of synapses, specialized junctions that regulate signal transmission between and across cells. Some of these junctions inhibit signal transmission, others accelerate it--a millisecond-by-millisecond balancing act which ensures that our brains function with maximum efficiency.

Now a new study by researchers at Harvard Medical School and at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard shows that this delicate equilibrium between inhibition and excitation is maintained, at least in part, by a highly specialized subset of microglia--the brain's resident immune cells, known for their role in fighting infection and cleanup of cellular debris.

The research, conducted in mice and published July 6 in Cell, reveals for the first time that this cadre of specialized immune cells is finely attuned to detecting and engaging exclusively with inhibitory synapses, the junctions that slow down the flow of information from cell to cell.

"We found that specialized immune and neuronal cells engage in important communication during early brain development and form interactions critical to the establishment of balanced brain wiring," said study first author Emilia Favuzzi, research fellow in neurobiology in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS and a postdoctoral scholar at the Broad. "Our observations suggest that microglia engage in an act of intricate interplay with specific types of synapses, homing in on them and sculpting the nervous system in a synapse-by-synapse manner," said study senior investigator Gordon Fishell, professor of neurobiology in the Blavatnik Institute at HMS and group leader in the Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at the Broad. "This is the first time we have shown that certain types of microglia are recruited to certain types of synapses and engage with them in a very specific way."

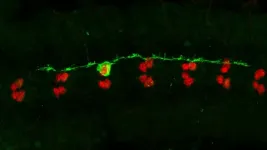

Moreover, the research showed, these cells interact with inhibitory synapses through direct physical contact, a first-of-a-kind observation enabled by advanced imaging techniques that allowed the researchers to observe in real time how cells in the brains of mice engage with one another.

The contact, the experiments showed, occurs via a GABA receptor that resides on the surface of microglia and renders these cells exquisitely attuned to GABA-emitting inhibitory synapses. GABA is the brain's main inhibitory neurotransmitter and acts as a brake on cell-to-cell signaling. GABA, the research showed, appears to act as a come-hither signal to a specific subset of microglia, inviting these cells to feast on inhibitory, GABA-releasing synapses.

Furthermore, the experiments revealed the process occurs via a three-step engagement--movement, recognition, and ingestion. The work showed that GABA-sensitive microglia engulf inhibitory synapses in much the same way these cells act to devour pathogens or cellular trash.

The insights, the researchers said, could hold important clues for new therapeutic approaches for conditions in which the brain's neural wiring goes awry. Such defects can disrupt the fine equilibrium between excitation and inhibition and lead to serious functional aberrations in sensory perceptions--from sensory overstimulation, at one extreme, to sensory blunting, at the other. Such sensory disruptions are often seen in conditions such as autism-spectrum disorders, ADHD, or schizophrenia.

"In the not-too-distant future we can look for ways to selectively toggle or tweak the balance between excitatory and inhibitory connections in the brain through the recruitment of specialized microglia tasked with remodeling and pruning specific synapses," Favuzzi added.

Specialists and jacks-of-all-trades

Microglia have been long known for their role in recognizing and disarming microbes and cleaning up cellular debris in the central nervous system. But recent research has found evidence that these garbage-collecting cells may also moonlight as modulators of brain wiring. They organize the brain's neural circuitry by helping build neural connections and then by pruning them to remove synapses that are no longer needed. This growing body of research casts these immune cells in a new light, suggesting they can play versatile roles in wiring the brain.

Yet, precisely how microglia perform their synapse-modulating job has remained shrouded in mystery--one that the new study findings are beginning to unravel. The results show that microglia are specialized to selectively attach and engage with either inhibitory or excitatory synapses, exhibiting a striking molecular affinity toward one or the other. An initial set of experiments showed that depleting all microglia from the cells of mice disrupted both inhibitory and excitatory neural connections, an unsurprising finding that demonstrated microglia affect both types of neural junctions. But when researchers focused specifically on a subset of microglia with GABA receptors on their surface, they observed that these cells sought out and engaged exclusively with GABA-emitting inhibitory synapses.

In another pivotal experiment, the researchers removed GABA receptors from these specialized microglial cells. When they did so, these cells lost their appetite for inhibitory synapses. Compared with microglia that had intact GABA receptors, these modified cells formed very few connections with inhibitory synapses. At the same time, removing GABA receptors from microglial cells had no effect on excitatory synapses, once again underscoring their affinity for specific types of synapses.

Mice lacking GABA receptors on their microglial cells had an abundance of inhibitory synapses and exhibited high levels of inhibitory signaling in their neurons. By contrast, the activity of their excitatory neurons remained unchanged.

Next, using a new imaging technology called MERFISH, the researchers were able to visualize and differentiate between microglial cell subtypes in animals. The team then measured, with granular precision, how gene expression varied in microglia in the presence or absence of GABA receptors.

In a final step, researchers wanted to determine whether removing GABA receptors from the microglia cells would, in fact, lead to behavioral changes in the animals. It did.

Young animals lacking GABA receptors on their microglia showed the hallmarks of overabundant inhibitory response--they were disinterested and disengaged, ran and jumped less than their peers, and ventured outside of their immediate surroundings far less frequently, showing no interest in exploring the space around them.

But something interesting happened when these animals matured into adulthood.

When fully grown, these same mice became increasingly hyperactive. They ran and jumped more and ventured to explore their environment. Indeed, when the researchers analyzed the type and number of synapses, they observed that the overabundance of inhibitory synapses in the young animals had turned into deficiency by adulthood. This somewhat counterintuitive finding hints at an over-compensatory mechanism at play, the researchers said.

Taken together, these insights set the stage for treatments that can correct underlying deficiencies in synaptic wiring, Fishell said.

"With a better understanding of the range and specialization of microglia, we can begin to design therapies that allow for the correction of the nervous system when it's out of tune."

INFORMATION:

Co-authors included Shuhan Huang, Giuseppe Saldi, Loïc Binan, Leena Ibrahim, Marian Fernández-Otero, Yuqing Cao, Ayman Zeine, Adwoa Sefah, Karen Zheng, Qing Xu, Elizaveta Khlestova, Samouil Farhi, Richard Bonneau, Sandeep Robert Datta, and Beth Stevens.

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01 NS081297, R01 MH071679, UG3 MH120096, and P01 NS074972), EMBO (ALTF 444-2018), Hearst Fellowships, Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative (566615), and Harvard's Dean Initiative. Additional support came from National Institute of Mental Health grant RF1 MH121289, and a Broad Institute-Israel Science Foundation research grant, and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS072030).

Relevant disclosures: Co-author Beth Stevens serves on the scientific advisory board and is a minor shareholder of Annexon. Gordon Fishell is a founder of Regel.

The DOI for this paper will be 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.018.

The study will be posted at following the embargo lift

https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(21)00753-4