(Press-News.org) Researchers have shown how worms learn to optimise their foraging activity by switching their response to pheromones in the environment, according to a report published today in eLife.

The findings are an important advance in the field of animal behaviour, providing new insights on how sensory cues are integrated to facilitate foraging and navigation.

Foraging food is one of the most critical yet challenging activities for animals, with food often patchily distributed and other animals trying to find and consume the same resources.

An important consideration is how long to stay and exploit a food patch before moving on to find another. Leaving incurs the cost of exploring a new territory, whereas staying put means feeding in a patch where resources are depleting. So how do animals know when to leave?

Natural habitats are usually full of chemical cues, such as pheromones from other individuals, and it is thought that pheromones help animals orientate their search for food. This means they need to know whether pheromones point to an abundant food resource, or an already exploited one. To acquire this knowledge, they need to learn from experience.

"It has been shown that bumblebees learn from the positive or negative association with pheromones acquired from their most recent feeding experience, but whether this is the case for other animals is unclear," explains first author Martina Dal Bello, Postdoctoral Associate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Cambridge, US. "We wanted to investigate the foraging behaviours of Caenorhabditis elegans worms because we know that they can evaluate population density inside food patches using pheromones, and that both pheromones and food availability control when the worms decide to move on to a new food resource."

The team started with a test to assess the worms' patch-leaving behaviour. Worms fed on a small patch of bacteria for about five hours, at equal distance from two spots: one a blend of pheromones and the other a non-pheromone control. The worms left the original patch at very different times; those that left early were more likely to go to the pheromone spot, whereas those that left late avoided the pheromones.

Next, they wanted to test whether these behaviours provided any survival benefits, so they developed a mathematical model to calculate the benefit to the worms of changing their preference for pheromones in a patchy environment. In the model, worms in an already occupied food patch have three choices: remain in their food patch, switch to another occupied food patch, or disperse away to an unoccupied patch. The model showed that the strategy that maximises the food eaten by a worm aligns with what they observed in the previous experiment. A fraction of worms switch at the beginning, leaving the food patch before it is depleted and following pheromones to reach another occupied patch. Then, once the food patches are depleted, all worms will disperse to find other food sources. These late leavers avoid other depleted patches by reversing their preference for pheromones, because they now associate pheromones with a depleted food patch.

So how do the worms know to reverse their preference for pheromones? To find out, the researchers kept worms in four sets of conditions: one with food and pheromones; one with pheromones but without food; one with food but without pheromones; and one without any food or pheromones. They then monitored how the worms reacted to a blend of pheromones. As anticipated, worms that spent time in the presence of both food and pheromones moved towards the pheromone blend, whereas they avoided it if they were used to the environment with pheromones but without food. As with bumblebees, the worms learn to prefer pheromones based on their recent positive or negative experience with foraging.

"Our study explains why worms tend to leave food patches at different times," explains senior author Jeff Gore, Professor of Physics at MIT. "Those that leave early are exposed to pheromones when food is abundant and have a positive association with these cues, which leads them to seek them out again. By contrast, worms that leave later when food is sparse associate pheromones with being famished, and avoid pheromones when they move away from the patch. Taken together, these results show that worms learn to adapt to sensory cues in their environment to optimise food intake during foraging."

INFORMATION:

Media contact

Emily Packer, Media Relations Manager

eLife

e.packer@elifesciences.org

+44 (0)1223 855373

About eLife

eLife is a non-profit organisation created by funders and led by researchers. Our mission is to accelerate discovery by operating a platform for research communication that encourages and recognises the most responsible behaviours. We aim to publish work of the highest standards and importance in all areas of biology and medicine, including Ecology, while exploring creative new ways to improve how research is assessed and published. eLife receives financial support and strategic guidance from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Max Planck Society and Wellcome. Learn more at https://elifesciences.org/about.

To read the latest Ecology research published in eLife, visit https://elifesciences.org/subjects/ecology.

Synthetic biology offers a way to engineer cells to perform novel functions, such as glowing with fluorescent light when they detect a certain chemical. Usually, this is done by altering cells so they express genes that can be triggered by a certain input.

However, there is often a long lag time between an event such as detecting a molecule and the resulting output, because of the time required for cells to transcribe and translate the necessary genes. MIT synthetic biologists have now developed an alternative approach to designing such circuits, which relies exclusively ...

AMHERST, Mass. - City sprawl and road development is increasingly fragmenting the habitats that many plant and animal species need to survive. Ecologists have long known than sustainable development requires attention to ecological connectivity - the ability to keep plant and wildlife populations intact and healthy, typically by preserving large tracts of land or creating habitat corridors for animals. New research from the University of Massachusetts Amherst argues that it's not enough for ecological modelling to focus on the landscape. If we want the best-possible ecological management, we should consider ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Plant-based meat substitutes taste and chew remarkably similar to real beef, and the 13 items listed on their nutrition labels - vitamins, fats and protein -- make them seem essentially equivalent.

But a Duke University research team's deeper examination of the nutritional content of plant-based meat alternatives, using a sophisticated tool of the science known as 'metabolomics,' shows they're as different as plants and animals.

Meat-substitute manufacturers have gone to great lengths to make the plant-based product as meaty as possible, including adding leghemoglobin, an iron-carrying molecule from soy, and red beet, ...

Terence D. Capellini has been interested in how joints work for almost three decades. Part of it is due to personal experience, having sustained several joint injuries as a college ice hockey player and recently developing knee osteoarthritis. But the principal investigator of Harvard's Developmental and Evolutionary Genetics Lab has also seen the pain and limited mobility of loved ones who've received similar diagnoses and injuries.

"We have all these joints in the body and they don't look the same from one another," said Capellini, the Richard B. Wolf Associate Professor in the Department of Human Evolutionary ...

Pediatric melanoma is a rare disease with only around 400 cases diagnosed in the United States every year. To better understand this disease and how best to treat it, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital scientists created a registry called Molecular Analysis of Childhood MELanocytic Tumors (MACMEL). A paper on findings from the registry was published today in Cancer.

"What is different about the MACMEL registry is that it is prospective," said corresponding author Alberto Pappo, M.D., St. Jude Solid Tumor Division director. "We're seeing the vast majority of enrolled patients as part of the melanoma clinic at St. Jude. We can follow these patients and conduct detailed pathology and molecular analysis."

More ...

University of California San Diego School of Medicine researchers have identified a possible link between inadequate exposure to ultraviolet-B (UVB) light from the sun and an increased risk of colorectal cancer, especially as people age.

Reporting in the journal BMC Public Health, researchers investigated global associations between levels of UVB light -- one of several types of ultraviolet light that reach the Earth's surface -- in 2017 and rates of colorectal cancer across several age groups in 186 countries in 2018.

Lower UVB exposure was significantly correlated with higher rates of colorectal ...

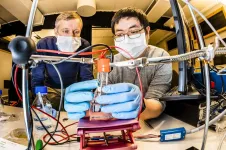

Manufacturing - Powered by nature

A team of researchers at Oak Ridge National Laboratory demonstrated the ability to additively manufacture power poles from bioderived and recycled materials, which could more quickly restore electricity after natural disasters.

Using the Big Area Additive Manufacturing system, the team 3D printed a 55-foot pole designed as a closed cylindrical structure. They evaluated three different composite materials with glass fibers including cellulose ester, recycled polycarbonate and bamboo fiber reinforced polystyrene.

"We developed a modular design that is easy to manufacture, transport and assemble," ORNL's Halil Tekinalp said. "Sections within the pole can ...

BOSTON - A skin pigmentation mechanism that can darken the color of human skin as a natural defense against ultraviolet (UV)-associated cancers has been discovered by scientists at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Mediating the biological process is an enzyme, NNT, which plays a key role in the production of melanin (a pigment that protects the skin from harmful UV rays) and whose inhibition through a topical drug or ointment could potentially reduce the risk of skin cancers. The study was published online in Cell.

"Skin pigmentation and its regulation are critically important because pigments confer major protection against UV-related cancers ...

A transplant of healthy gut microbes followed by fibre supplements benefits patients with severe obesity and metabolic syndrome, according to University of Alberta clinical trial findings published today in Nature Medicine.

Patients who were given a single-dose oral fecal microbial transplant followed by a daily fibre supplement were found to have better insulin sensitivity and higher levels of beneficial microbes in their gut at the end of the six-week trial. Improved insulin sensitivity allows the body to use glucose more effectively, reducing blood sugar.

"They were much more metabolically healthy," said principal investigator Karen Madsen, professor of medicine in the Faculty of Medicine ...

Researchers at Linköping University have developed a method that may lead to new types of displays based on structural colours. The discovery opens the way to cheap and energy-efficient colour displays and electronic labels. The study has been published in the scientific journal Advanced Materials.

We usually think of colours as created by pigments, which absorb light at certain wavelengths such that we perceive colour from other wavelengths that are scattered and reach our eyes. That's why leaves, for example, are green and tomatoes red. But colours can be created ...