(Press-News.org) UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- What if the COVID-19 virus could be used against itself? Researchers at Penn State have designed a proof-of-concept therapeutic that may be able to do just that. The team designed a synthetic defective SARS-CoV-2 virus that is innocuous but interferes with the real virus's growth, potentially causing the extinction of both the disease-causing virus and the synthetic virus.

"In our experiments, we show that the wild-type [disease-causing] SARS-CoV-2 virus actually enables the replication and spread of our synthetic virus, thereby effectively promoting its own decline," said Marco Archetti, associate professor of biology, Penn State. "A version of this synthetic construct could be used as a self-promoting antiviral therapy for COVID-19."

Archetti explained that when a virus attacks a cell, it attaches to the cell's surface and injects its genetic material into the cell. The cell is then tricked into replicating the virus's genetic material and packaging it into virions, which burst from the cell and go off to infect other cells.

'Defective interfering (DI)' viruses, which are common in nature, contain large deletions in their genomes that often affect their ability to replicate their genetic material and package it into virions. However, DI genomes can perform these functions if the cell they've infected also harbors genetic material from a wild-type virus. In this case, a DI genome can hijack a wild-type genome's replication and packaging machinery.

"These defective genomes are like parasites of the wild-type virus," said Archetti, explaining that when a DI genome utilizes of a wild-type genome's machinery, it also can impair the wild-type genome growth.

In addition, he said, "given the shorter length of their genomes as a result of the deletions, DI genomes can replicate faster than wild-type genomes in coinfected cells and quickly outcompete the wild-type."

Indeed, in their new study, which published today (July 1) in the journal PeerJ, Archetti and his colleagues found that their synthetic DI genome can replicate three times faster than the wild-type genome, resulting in a reduction of the wild-type viral load by half in 24 hours.

To conduct their study, the researchers engineered short synthetic DI genomes from parts of the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 genome and introduced them into African green monkey cells that were already infected with the wild-type SARS-CoV-2 virus. Next, they quantified the relative amounts of the DI and WT genomes in the cells over time points, which gave an indication of the amount of interference of the DI genome with the wild-type genome.

The team found that within 24 hours of infection, the DI genome reduced the amount of SARS-CoV-2 by approximately half compared to the amount of wild-type virus in control experiments. They also found that the the DI genome increases in quantity 3.3 times as fast than the wild-type virus.

Archetti said that while the 50% reduction in virus load that they observed over 24 hours is not enough for therapeutic purposes, presumably, as the DI genomes increase in frequency in the cell, the decline in the amount of wild-type virus would lead to the demise of both the virus and the DI genome, as the DI genome cannot persist once it has driven the wild-type virus to extinction.

He added that further experiments are needed to verify the potential of SARS-CoV-2 DIs as an antiviral treatment, suggesting that the experiments could be repeated in human lung cell lines, and against some of the newer variants of SARS-CoV-2. Furthermore, he said, an efficient delivery method should be devised. In further work that is still unpublished, the team has now used nanoparticles as a delivery vector and observed that the virus declines by more than 95% in 12 hours.

"With some additional research and finetuning, a version of this synthetic DI could be used as a self-sustaining therapeutic for COVID-19."

INFORMATION:

Other Penn State authors on the paper include Shun Yao, postdoctoral scholar in biology; Anoop Narayanan, associate research professor of biochemistry and molecular biology; Sydney Majowicz, graduate student in molecular, cellular, and integrative biosciences; and Joyce Jose, assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology.

The Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences at Penn State supported this research.

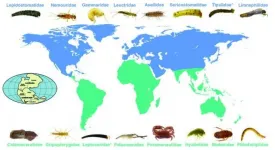

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- The fast-moving decline and extinction of many species of detritivores -- organisms that break down and remove dead plant and animal matter -- may have dire consequences, an international team of scientists suggests in a new study.

The researchers observed a close relationship between detritivore diversity and plant litter decomposition in streams, noting that decomposition was highest in waters with the most species of detritivores -- including aquatic insects such as stoneflies, caddisflies, mayflies and craneflies, and crustaceans such as scuds and freshwater shrimp and crabs.

Decomposition ...

ABINGTON, Pa. -- Counterfeit dominance decreases Anglo-American, but not Asian, consumers' quality perception and purchase intention of authentic brands, according to a team of researchers.

"Counterfeit dominance is the perception that counterfeit products possess more than 50% of market share," Lei Song, assistant professor of marketing at Penn State Abington, said. "Counterfeit dominance is a phenomenon especially concerning for the luxury fashion industry as counterfeit luxury fashion brands account for 60% to 70% of the $4.5 trillion in total counterfeit trade and one-quarter of total sales in luxury fashion goods."

Lei and his team conducted four behavioral experiments with 149 participants on ...

Increased labour mobility seems to have stopped the racial wage discrimination of black English football players. A new study in economics from Stockholm university and Université Paris-Saclay used data from the English Premier League to investigate the impact of the so-called "Bosman ruling", and found that racial discrimination against English football players disappeared - but not for non-EU players. The study was recently published in the journal European Economic Review.

In 1995, the so-called Bosman ruling turned the labour market for European footballers upside down, introducing a free transfer ...

Necessity is the father of invention, but where is its mother? According to a new study published in Science, fewer women hold biomedical patents, leading to a reduced number of patented technologies designed to address problems affecting women.

While there are well-known biases that limit the number of women in science and technology, the consequences extend beyond the gender gap in the labour market, say researchers from McGill University, Harvard Business School, and the Universidad de Navarra in Barcelona. Demographic inequities in who gets to invent lead to demographic inequities in who benefits from invention.

"Although the percentage of biomedical patents held by women has risen from 6.3% to 16.2% over the last three decades, ...

Researchers from Pompeu Fabra University (Barcelona, Spain) have analysed the way citizen science is practised in Spain. The paper, produced by Carolina Llorente and Gema Revuelta, from UPF's Science, Communication and Society Studies Centre (CCS-UPF) and Mar Carrió, from the University's Health Sciences Educational Research Group (GRECS), has been published in the Journal of Science Communication (JCOM).

Based on the study, a series of recommendations have been put forward to improve how citizen participation in science is carried out. Firstly, they suggest efforts be stepped up regarding the training given for assessing these initiatives or the creation of multi-disciplinary teams with a broad range of ...

Using an exceptionally preserved fossil from South Africa, a particle accelerator, and high-powered x-rays, an international team including a University of Minnesota researcher has discovered that not all dinosaurs breathed in the same way. The findings give scientists more insight into how a major group of dinosaurs, including well-known creatures like the triceratops and stegosaurus, evolved.

The study is published in eLife, a peer-reviewed open access scientific journal for the biomedical and life sciences.

Not all animals use the same techniques and organs to breathe. Humans expand and contract their ...

Researchers have shown how worms learn to optimise their foraging activity by switching their response to pheromones in the environment, according to a report published today in eLife.

The findings are an important advance in the field of animal behaviour, providing new insights on how sensory cues are integrated to facilitate foraging and navigation.

Foraging food is one of the most critical yet challenging activities for animals, with food often patchily distributed and other animals trying to find and consume the same resources.

An important consideration is how long to stay and exploit a food patch before moving on to find another. Leaving incurs the cost ...

Synthetic biology offers a way to engineer cells to perform novel functions, such as glowing with fluorescent light when they detect a certain chemical. Usually, this is done by altering cells so they express genes that can be triggered by a certain input.

However, there is often a long lag time between an event such as detecting a molecule and the resulting output, because of the time required for cells to transcribe and translate the necessary genes. MIT synthetic biologists have now developed an alternative approach to designing such circuits, which relies exclusively ...

AMHERST, Mass. - City sprawl and road development is increasingly fragmenting the habitats that many plant and animal species need to survive. Ecologists have long known than sustainable development requires attention to ecological connectivity - the ability to keep plant and wildlife populations intact and healthy, typically by preserving large tracts of land or creating habitat corridors for animals. New research from the University of Massachusetts Amherst argues that it's not enough for ecological modelling to focus on the landscape. If we want the best-possible ecological management, we should consider ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- Plant-based meat substitutes taste and chew remarkably similar to real beef, and the 13 items listed on their nutrition labels - vitamins, fats and protein -- make them seem essentially equivalent.

But a Duke University research team's deeper examination of the nutritional content of plant-based meat alternatives, using a sophisticated tool of the science known as 'metabolomics,' shows they're as different as plants and animals.

Meat-substitute manufacturers have gone to great lengths to make the plant-based product as meaty as possible, including adding leghemoglobin, an iron-carrying molecule from soy, and red beet, ...