Giant water plumes erupting from Enceladus have long fascinated scientists and the public alike, inspiring research and speculation about the vast ocean that is believed to be sandwiched between the moon's rocky core and its icy shell. Flying through the plumes and sampling their chemical makeup, the Cassini spacecraft detected a relatively high concentration of certain molecules associated with hydrothermal vents on the bottom of Earth's oceans, specifically dihydrogen, methane and carbon dioxide. The amount of methane found in the plumes was particularly unexpected.

"We wanted to know: Could Earthlike microbes that 'eat' the dihydrogen and produce methane explain the surprisingly large amount of methane detected by Cassini?" said Regis Ferriere, an associate professor in the University of Arizona Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and one of the study's two lead authors. "Searching for such microbes, known as methanogens, at Enceladus' seafloor would require extremely challenging deep-dive missions that are not in sight for several decades."

Ferriere and his team took a different, easier route: They constructed mathematical models to calculate the probability that different processes, including biological methanogenesis, might explain the Cassini data.

The authors applied new mathematical models that combine geochemistry and microbial ecology to analyze Cassini plume data and model the possible processes that would best explain the observations. They conclude that Cassini's data are consistent either with microbial hydrothermal vent activity, or with processes that don't involve life forms but are different from the ones known to occur on Earth.

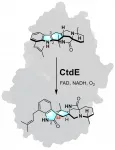

On Earth, hydrothermal activity occurs when cold seawater seeps into the ocean floor, circulates through the underlying rock and passes close by a heat source, such as a magma chamber, before spewing out into the water again through hydrothermal vents. On Earth, methane can be produced through hydrothermal activity, but at a slow rate. Most of the production is due to microorganisms that harness the chemical disequilibrium of hydrothermally produced dihydrogen as a source of energy, and produce methane from carbon dioxide in a process called methanogenesis.

The team looked at Enceladus' plume composition as the end result of several chemical and physical processes taking place in the moon's interior. First, the researchers assessed what hydrothermal production of dihydrogen would best fit Cassini's observations, and whether this production could provide enough "food" to sustain a population of Earthlike hydrogenotrophic methanogens. To do that, they developed a model for the population dynamics of a hypothetical hydrogenotrophic methanogen, whose thermal and energetic niche was modeled after known strains from Earth.

The authors then ran the model to see whether a given set of chemical conditions, such as the dihydrogen concentration in the hydrothermal fluid, and temperature would provide a suitable environment for these microbes to grow. They also looked at what effect a hypothetical microbe population would have on its environment - for example, on the escape rates of dihydrogen and methane in the plume.

"In summary, not only could we evaluate whether Cassini's observations are compatible with an environment habitable for life, but we could also make quantitative predictions about observations to be expected, should methanogenesis actually occur at Enceladus' seafloor," Ferriere explained.

The results suggest that even the highest possible estimate of abiotic methane production - or methane production without biological aid - based on known hydrothermal chemistry is far from sufficient to explain the methane concentration measured in the plumes. Adding biological methanogenesis to the mix, however, could produce enough methane to match Cassini's observations.

"Obviously, we are not concluding that life exists in Enceladus' ocean," Ferriere said. "Rather, we wanted to understand how likely it would be that Enceladus' hydrothermal vents could be habitable to Earthlike microorganisms. Very likely, the Cassini data tell us, according to our models.

"And biological methanogenesis appears to be compatible with the data. In other words, we can't discard the 'life hypothesis' as highly improbable. To reject the life hypothesis, we need more data from future missions," he added.

The authors hope their paper provides guidance for studies aimed at better understanding the observations made by Cassini and that it encourages research to elucidate the abiotic processes that could produce enough methane to explain the data.

For example, methane could come from the chemical breakdown of primordial organic matter that may be present in Enceladus' core and that could be partially turned into dihydrogen, methane and carbon dioxide through the hydrothermal process. This hypothesis is very plausible if it turns out that Enceladus formed through the accretion of organic-rich material supplied by comets, Ferriere explained.

"It partly boils down to how probable we believe different hypotheses are to begin with," he said. "For example, if we deem the probability of life in Enceladus to be extremely low, then such alternative abiotic mechanisms become much more likely, even if they are very alien compared to what we know here on Earth."

According to the authors, a very promising advance of the paper lies in its methodology, as it is not limited to specific systems such as interior oceans of icy moons and paves the way to deal with chemical data from planets outside the solar system as they become available in the coming decades.

INFORMATION:

A full list of authors and funding information can be found in the paper, "Bayesian analysis of Enceladus's plume data to assess methanogenesis," in the July 7 issue of Nature Astronomy.