(Press-News.org) The UK public is likely to take the COVID-19 pandemic less seriously once restrictions are lifted, according to new research led by Cardiff University.

Psychologists found lockdown in itself was a primary reason why so many people were willing to abide by the rules from the start - believing the threat must be severe if the government imposes such drastic measures.

The team from Cardiff and the universities of Bath and Essex examined the reasons behind headline polling support for COVID-19 measures. They carried out two UK surveys*, six months apart, during 2020. Their findings are published today in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Lead author Dr Colin Foad said: "Surprisingly, we found that people judge the severity of the COVID-19 threat based on the fact the government imposed a lockdown - in other words, they thought 'it must be bad if government's taking such drastic measures'.

"We also found that the more they judged the risk in this way, the more they supported lockdown. This suggests that if and when 'Freedom Day' comes and restrictions are lifted, people may downplay the threat of COVID."

The research also found:

- Raising people's personal threat was unlikely to enhance their support for restrictive measures;

- People supported lockdown yet thought many of its side effects were "unacceptable" in a cost-benefit analysis.

Dr Foad said: "The pandemic has been characterised by strong public support for lockdowns, but our research suggests that people have actually been much more conflicted than the headline polls suggest.

"For example, we found that when people think about the costs of this policy, such as detriment to mental health and reduced access to treatment for non-COVID health problems, these can outweigh its benefits."

On the finding around personal threat, he said: "In order to try and keep public support for lockdowns high, various strategies have been tried by the government, including reminding people that they and their loved ones are at risk from COVID-19.

"However, we find that most people's personal sense of threat does not relate to their support for restrictions. Instead, people judged the threat at a much more general level, such as towards the country as a whole. So, any messaging that targets their personal sense of threat is unlikely to actually raise support for any further restrictions."

The researchers warned there was a risk of public opinion and government policy "forming a symbiotic relationship", which could affect how policies are implemented now and in future.

Professor Lorraine Whitmarsh, an environmental psychologist from the University of Bath, said: "This has important implications for how we deal with other risks, like climate change - the public will be more likely to believe it's a serious problem if governments implement bold policies to tackle it."

Professor Whitmarsh suggested bold actions might include stopping all road building (as has happened recently in Wales) or blocking airport expansions.

The researchers are calling for more nuanced use of polling data during the pandemic to accurately gauge the diversity and complexity of public opinion.

Dr Paul Hanel, a lecturer in psychology at the University of Essex, said: "Polling data from large samples are important in understanding what people think. Our study, however, shows that it is crucial to ask the right questions because otherwise we are only getting a limited and potentially even misleading picture of how diverse and even conflicting public opinions truly are."

INFORMATION:

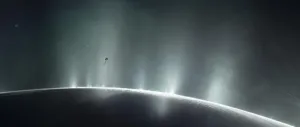

An unknown methane-producing process is likely at work in the hidden ocean beneath the icy shell of Saturn's moon Enceladus, suggests a new study published in Nature Astronomy by scientists at the University of Arizona and Paris Sciences & Lettres University.

Giant water plumes erupting from Enceladus have long fascinated scientists and the public alike, inspiring research and speculation about the vast ocean that is believed to be sandwiched between the moon's rocky core and its icy shell. Flying through the plumes and sampling their chemical makeup, the Cassini spacecraft detected a relatively high concentration of certain molecules associated with hydrothermal vents on the bottom of Earth's oceans, specifically dihydrogen, ...

Using artificial intelligence, UT Southwestern scientists have identified thousands of genetic mutations likely to affect the immune system in mice. The work is part of one Nobel laureate's quest to find virtually all such variations in mammals.

"This study identifies 101 novel gene candidates with greater than 95% chance of being required for immunity," says END ...

Five Simon Fraser University scholars are among international scientists sounding an alarm over the "pervasive social and ecological consequences" of the destruction and suppression of the knowledge systems of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

Their paper, published today in the Journal of Ethnobiology, draws on the knowledge of 30 international Indigenous and non-Indigenous co-authors, and highlights 15 strategic actions to support the efforts of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in sustaining their knowledge systems and ties to lands.

Study co-lead, SFU archaeology professor Dana Lepofsky, says, "We ...

AMHERST, Mass. - Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst recently discovered that the ability of agricultural grasses to withstand drought is directly related to the health of the microbial community living on their stems, leaves and seeds.

"Microbes do an enormous amount for the grasses that drive the world's agriculture," says Emily Bechtold, a graduate student in UMass Amherst's microbiology department and lead author of the paper recently published in Applied and Environmental Microbiology. "They protect from pathogens, provide the grass with nutrients such as nitrogen, supply hormones to bolster the plant's health and growth, protect from UV radiation ...

Veterinarians at the University of California, Davis, have found that a cat's DNA alters how it responds to a life-saving medication used to treat hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, or HCM, a heart disease that affects 1 in 7 cats. The END ...

A new national study published in Psychiatric Services finds that over a quarter of US adults with depression or anxiety symptoms reported needing mental health counseling but were not able to access it during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers analyzed data from nearly 70,000 adults surveyed in the US Census Household Pulse Survey in December 2020.

"Social isolation, COVID-related anxiety, disruptions in normal routines, job loss, and food insecurity have led to a surge in mental illness during the pandemic," said lead author, END ...

Des Plaines, IL - The Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (SAEM) is pleased to announce the release of the first publication in a series of Guidelines for Reasonable and Appropriate Care in the Emergency Department (GRACE), which focuses on low-risk chest pain. The article, titled " END ...

People who receive mRNA COVID-19 vaccines are up to 91 percent less likely to develop the disease than those who are unvaccinated, according to a new nationwide study of eight sites, including Salt Lake City. For those few vaccinated people who do still get an infection, or "breakthrough" cases, the study suggests that vaccines reduce the severity of COVID-19 symptoms and shorten its duration.

Researchers say these results are among the first to show that mRNA vaccination benefits even those individuals who experience breakthrough infections.

"One of the unique things about this study is that it measured the secondary benefits of the vaccine," says END ...

When traffic is clogged at a downtown intersection, there may be a way to reduce some of the congestion: Eliminate a few left turns.

According to Vikash Gayah, associate professor of civil engineering at Penn State, well-placed left-turn restrictions in certain busy intersections could loosen many of the bottlenecks that hamper traffic efficiency. He recently created a new method that could help cities identify where to restrict these turns to improve overall traffic flow.

"We have all experienced that feeling of getting stuck waiting to make a left turn," Gayah said. "And ...

Using simple blood tests could help researchers identify children who have been misidentified as having severe malaria, according to a study published today in eLife.

Researchers are working to develop better ways to treat severe malaria, which kills about 400,000 children in Africa each year. The discovery could help expedite such research by helping them more accurately identify children with severe malaria. It also reinforces the importance of the World Health Organization's recommendation that all children being treated for severe malaria also receive antibiotics to ensure any misdiagnosed children receive life-saving care.

Diagnosing severe malaria in children in Africa is challenging because the ...