(Press-News.org) In a new study on mice, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers report that using MRI scans to measure blood volume in the brain can serve as a noninvasive way to potentially track the progress of gene editing therapies for early-stage Huntington's disease, a neurodegenerative disorder that attacks brain cells. The researchers say that by identifying and treating the mutation known to cause Huntington's disease with this type of gene therapy, before a patient starts showing symptoms, it may slow progression of the disease.

The findings of the study were published May 27 in the journal Brain.

"What's exciting about this study is the opportunity to identify a reliable biomarker that can track the potential success of genetic therapies before patients start manifesting symptoms," says Wenzhen Duan, M.D., Ph.D., director of the translational neurobiology laboratory and professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. "Such a biomarker could facilitate the development of new treatments, and help us determine the best time to begin them."

Huntington's disease is a rare genetic disorder caused by a single defective gene, dubbed "huntingtin," on human chromosome 4. The gene is passed on from parents to children -- if one parent has the mutation, each child has a 50% chance of inheriting it. Huntington's disease has no cure and can lead to emotional disturbances, loss of intellectual abilities and uncontrolled movements. Thanks to genetic testing, people can know if they have the disease long before symptoms arise, which typically happens in their 40s or 50s.

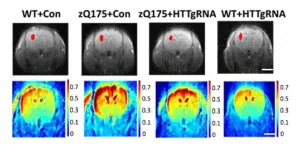

For the study, Duan and her team collaborated with colleagues from Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, who developed a novel method to more precisely measure the blood volume in the brain by using advanced functional MRI scans. With the scans, they can map the trajectory of blood flow in small blood vessels called arterioles in the brains of mice engineered to carry the human huntingtin gene mutation that mirror the early stages of Huntington's disease in humans.

Duan notes that there are many known metabolic changes in the brains of people with Huntington's disease, and those changes initiate a brain blood volume response in the disease's early stages. Blood volume is a key marker for oxygen supply to brain cells, which in turn supplies energy for the neurons to function. But with Huntington's disease, the brain's arteriolar blood volume is dramatically diminished, which makes the neurons deteriorate because of lack of oxygen as the disease progresses.

In a series of experiments, the researchers suppressed the mutation in the huntingtin gene in mice, using a gene-editing technology known as CRISPR -- a tool for editing genomes that allows the alteration of a DNA sequence to modify gene function. Then, they used the MRI scanning technique and other tests to track the brain function over time both of mice with the huntingtin mutation, in which they edited out the faulty gene sequence, and a control group of mice in which the faulty gene was unedited.

The experiments assessed abnormalities in the trajectory of arteriolar blood volumes in mouse brains with the Huntington's disease mutation at 3, 6 and 9 months of age (pre-symptom stage, beginning of symptoms and post-symptom stage, respectively). The researchers looked at whether suppression of the mutant huntingtin gene in the neurons could normalize altered arteriolar blood volumes in the pre-symptom stage, and whether reduced expression of the huntingtin gene at the pre-symptom stage could delay or even prevent development of symptoms.

"Overall, our data suggest that the cerebral arteriolar blood volume measure may be a promising noninvasive biomarker for testing new therapies in patients with Huntington's who are yet to show symptoms of the disease," says Duan. "Introducing treatment in this early stage may have long-lasting benefits."

When the researchers mapped the trajectory of cerebral blood volume and conducted an assortment of brain and motor tests in the mice at 3 months of age, and compared the test to those of the control group, they observed no significant differences except in cerebral blood volumes. However, Huntington's symptoms in the mice with the huntingtin gene started at 6 months of age and progressively worsened at 9 months, suggesting that altered cerebral blood volume occurs before motor symptoms and atrophy of the brain cells -- typical traits of the disease.

The cerebral blood volume changes were also found to be similar to those observed in patients with Huntington's disease before they start manifesting symptoms, which declines with the start of symptoms and while the disease progresses over time.

The researchers also analyzed the structure of the arteriole blood vessels in the brains of mice with the mutant huntingtin gene at 3 and at 9 months of age and found no differences in the numbers of vessel segments in the pre-symptom stage. However, they observed that smaller blood vessels had an increased density and reduced diameter, which may be a vascular response to compensate for the impaired neuronal brain function. This might suggest, the researchers conclude, that impaired vascular structure leads to lowered arteriole blood volumes and possibly compromised ability to compensate for the loss in the symptom stage.

Considering that Huntington's disease symptoms depend not only on brain cell loss but also on how neurons deteriorate, the researchers set out to determine if suppressing the huntingtin gene during the pre-symptom stage in mice could delay or even prevent disease progression. To do that, the researchers introduced the altered huntingtin gene to the neurons in mice at 2 months of age and evaluated the outcomes at 3 months of age (when no atrophy or motor deficits were present).

Remarkably, the researchers say, the cerebral arteriolar blood volume in mice with the altered huntingtin gene was This suggests that the altered cerebral blood volume during the pre-symptom stage in mice is most likely due to neuronal changes in either activity or metabolism.

"Our findings demonstrate that significant changes in arteriolar cerebral blood volumes occur before neurons start to degenerate and symptoms begin, further supporting the idea that altered cerebrovascular function is an early stage symptom in Huntington's disease," says Duan. She explains that these changes also indicate there's a pre-symptom therapeutic window in which to test interventions. While no animal model replicates all the symptoms of human Huntington's disease, this research offers an alternative system to study functional changes in the pre-symptom stage, she says.

Further validation of these findings in human clinical trials would facilitate development of efficient therapeutic interventions for patients with Huntington's disease before they start developing symptoms. "The goal is to delay or even conceivably prevent the manifestation of Huntington's disease altogether," says Duan.

Along with Duan, other researchers who contributed to the work are Hongshuai Liu, Chuangchuang Zhang, Jing Jin, Liam Cheng, Qian Wu, Zhiliang Wei, Peiying Liu and Christopher Ross from Johns Hopkins, and Jiadi Xu, Xinyuan Miao, Hanzhang Lu, Peter van Zijl and Jun Hua from the Kennedy Krieger Institute and Johns Hopkins.

INFORMATION:

Hamilton, ON (July 7, 2021) - A McMaster University team of researchers recently discovered how, exactly, the COVID-19 vaccines that use adenovirus vectors trigger a rare but sometimes fatal blood clotting reaction called vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia or VITT.

The findings will put scientists on the path of finding a way to better diagnose and treat VITT, possibly prevent it and potentially make vaccines safer.

The researchers' article was fast-tracked for publication today by the prestigious journal Nature in its accelerated article preview because of the importance of the research.

"Our work also answers important ...

A genetic map of an aggressive childhood brain tumour called medulloblastoma has helped researchers identify a new generation anti-cancer drug that can be repurposed as an effective treatment for the disease.

This international collaboration, led by researchers from The University of Queensland's (UQ) Diamantina Institute and WEHI in Melbourne, could give parents hope in the fight against the most common and fatal brain cancer in children.

UQ lead researcher Dr Laura Genovesi said the team had mapped the genetics of these aggressive brain tumours for five ...

Some exceptionally gifted people have marked human history and culture. Leonardo, Mozart, and Einstein are some famous examples of this phenomenon.

Is talent in a given field a uniquely human phenomenon? We do not know whether gifted bees or elephants exist, just to name a few species, but now there is evidence that talent in a specific field exists, in at least one non-human species: the dog.

A new study, just published in Scientific Reports, found that, while the vast majority of dogs struggle to learn object labels (such as the names of their toys), when tested in strictly controlled conditions, a handful of gifted word learner ...

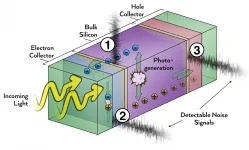

As society moves towards a renewable energy future, it's crucial that solar panels convert light into electricity as efficiently as possible. Some state-of-the-art solar cells are close to the theoretical maximum of efficiency--and physicists from the University of Utah and Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin have figured out a way to make them even better.

In a new study, physicists used a technique known as cross-correlation noise spectroscopy to measure miniscule fluctuations in electrical current flowing between materials inside silicon solar cells. The researchers identified crucial electrical ...

Nature has a vast store of medicinal substances. "Over 50 percent of all drugs today are inspired by nature," says Gisbert Schneider, Professor of Computer-Assisted Drug Design at ETH Zurich. Nevertheless, he is convinced that we have tapped only a fraction of the potential of natural products. Together with his team, he has successfully demonstrated how artificial intelligence (AI) methods can be used in a targeted manner to find new pharmaceutical applications for natural products. Furthermore, AI methods are capable of helping to find alternatives to these compounds that have the same effect but are much easier and therefore cheaper to ...

Researchers at the IBS Center for Quantum Nanoscience at Ewha Womans University (QNS) have shown that dysprosium atoms resting on a thin insulating layer of magnesium oxide have magnetic stability over days. In a study published in Nature Communications they have proven that these tiny magnets have extreme robustness against fluctuations in magnetic field and temperature and will flip only when they are bombarded with high energy electrons through the STM-tip.

Using these ultra-stable and yet switchable single-atom magnets, the team has shown atomic-scale control of the magnetic field within ...

Dr Bock, under the mentorship of Distinguished Professor Dietmar Hutmacher, from QUT Centre for Biomedical Technologies, has focused her research on bone metastases from breast and prostate cancers.

She developed 3D miniature bone-like tissue models in which 3D printed biomimetic scaffolds are seeded with patient-derived bone cells and tumour cells to be used as clinical and preclinical drug testing tools.

The research team investigated their hypothesis that traditional anti-androgen therapy had limited effect in the microenvironment of prostate cancer bone tumours. The team's findings are published in Science Advances.

"We wanted to see if the therapy could be a contributor of cancer cells' adaptive responses that fuelled bone ...

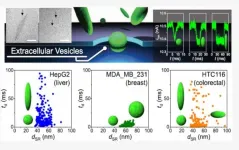

A recent study by scientists from Japanese universities has shown that the shape of cell-derived nanoparticles, known as "extracellular vesicles" (EVs), in body fluids could be a biomarker for identifying types of cancer. In the study, the scientists successfully measured the shape distributions of EVs derived from liver, breast, and colorectal cancer cells, showing that the shape distributions differ from one another. The findings were recently published in the journal Analytical Chemistry.

Early detection of cancerous tumors in the body is essential for ...

New York, NY (July 6, 2021) - Mount Sinai researchers have uncovered the complex cellular mechanisms of Ebola virus, which could help explain its severe toll on humans and identify potential pathways to treatment and prevention. In a study published in mBio, the team reported how a protein of the Ebola virus, VP24, interacts with the double-layered membrane of the cell nucleus (known as the nuclear envelope), leading to significant damage to cells along with virus replication and the propagation of disease.

"The Ebola virus is extremely skilled at dodging the body's immune defenses, and in our study we characterize an important way in which that evasion occurs through disruption of the nuclear envelope, mediated by the VP24 protein," says co-senior ...

QUT PhD researcher Zachariah Schuurs said the research team had identified a new binding site on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

"Binding of the CoV-2 spike protein to heparan sulphate (HS) on cell surfaces is generally the first step in a cascade of interactions the virus needs to initiate an infection and enter the cell.

"Most research has focused on understanding how HS interacts on the receptor-binding domain (RBD) and furin cleavage site of the SARS-CoV-2 virus's spike protein, as these typically bind different types of drugs, vaccines and antibodies.

"We have identified a novel binding site on the N-terminal domain (NTD), a different area of the virus's spike that facilitates the binding of HS. This helps to better understand how the virus ...