INFORMATION:

This research was supported, in part, by the Office of Nuclear Physics, U.S. Department of Energy; the MISTI Global Seed Funds; the European Research Council; the Belgian FWO Vlaanderen and BriX IAP Research Program; the German Research Foundation; the UK Science and Technology Facilities Council, and the Ernest Rutherford Fellowship Grant.

New clues to why there's so little antimatter in the universe

Radioactive molecules are sensitive to subtle nuclear phenomena and might help physicists probe the violation of the most fundamental symmetries of nature.

2021-07-07

(Press-News.org) Imagine a dust particle in a storm cloud, and you can get an idea of a neutron's insignificance compared to the magnitude of the molecule it inhabits.

But just as a dust mote might affect a cloud's track, a neutron can influence the energy of its molecule despite being less than one-millionth its size. And now physicists at MIT and elsewhere have successfully measured a neutron's tiny effect in a radioactive molecule.

The team has developed a new technique to produce and study short-lived radioactive molecules with neutron numbers they can precisely control. They hand-picked several isotopes of the same molecule, each with one more neutron than the next. When they measured each molecule's energy, they were able to detect small, nearly imperceptible changes of the nuclear size, due to the effect of a single neutron.

The fact that they were able to see such small nuclear effects suggests that scientists now have a chance to search such radioactive molecules for even subtler effects, caused by dark matter, for example, or by the effects of new sources of symmetry violations related to some of the current mysteries of the universe.

"If the laws of physics are symmetrical as we think they are, then the Big Bang should have created matter and antimatter in the same amount. The fact that most of what we see is matter, and there is only about one part per billon of antimatter, means there is a violation of the most fundamental symmetries of physics, in a way that we can't explain with all that we know," says Ronald Fernando Garcia Ruiz, assistant professor of physics at MIT.

"Now we have a chance to measure these symmetry violations, using these heavy radioactive molecules, which have extreme sensitivity to nuclear phenomena that we cannot see in other molecules in nature," he says. "That could provide answers to one of the main mysteries of how the universe was created."

Ruiz and his colleagues have published their results today in Physical Review Letters.

A special asymmetry

Most atoms in nature host a symmetrical, spherical nucleus, with neutrons and protons evenly distributed throughout. But in certain radioactive elements like radium, atomic nuclei are weirdly pear-shaped, with an uneven distribution of neutrons and protons within. Physicists hypothesize that this shape distortion can enhance the violation of symmetries that gave origin to the matter in the universe.

"Radioactive nuclei could allow us to easily see these symmetry-violating effects," says study lead author Silviu-Marian Udrescu, a graduate student in MIT's Department of Physics. "The disadvantage is, they're very unstable and live for a very short amount of time, so we need sensitive methods to produce and detect them, fast."

Rather than attempt to pin down radioactive nuclei on their own, the team placed them in a molecule that futher amplifies the sensitivity to symmetry violations. Radioactive molecules consist of at least one radioactive atom, bound to one or more other atoms. Each atom is surrounded by a cloud of electrons that together generate an extremely high electric field in the molecule that physicists believe could amplify subtle nuclear effects, such as effects of symmetry violation.

However, aside from certain astrophysical processes, such as merging neutron stars, and stellar explosions, the radioactive molecules of interest do not exist in nature and therefore must be created artificially. Garcia Ruiz and his colleagues have been refining techniques to create radioactive molecules in the lab and precisely study their properties. Last year, they reported on a method to produce molecules of radium monofluoride, or RaF, a radioactive molecule that contains one unstable radium atom and a fluoride atom.

In their new study, the team used similar techniques to produce RaF isotopes, or versions of the radioactive molecule with varying numbers of neutrons. As they did in their previous experiment, the researchers utilized the Isotope mass Separator On-Line, or ISOLDE, facility at CERN, in Geneva, Switzerland, to produce small quantities of RaF isotopes.

The facility houses a low-energy proton beam, which the team directed toward a target -- a half-dollar-sized disc of uranium-carbide, onto which they also injected a carbon fluoride gas. The ensuing chemical reactions produced a zoo of molecules, including RaF, which the team separated using a precise system of lasers, electromagnetic fields, and ion traps.

The researchers measured each molecule's mass to estimate of the number of neutrons in a molecule's radium nucleus. They then sorted the molecules by isotopes, according to their neutron numbers.

In the end, they sorted out bunches of five different isotopes of RaF, each bearing more neutrons than the next. With a separate system of lasers, the team measured the quantum levels of each molecule.

"Imagine a molecule vibrating like two balls on a spring, with a certain amount of energy," explains Udrescu, who is a graduate student of MIT's Laboratory for Nuclear Science. "If you change the number of neutrons in one of these balls, the amount of energy could change. But one neutron is 10 million times smaller than a molecule, and with our current precision we didn't expect that changing one would create an energy difference, but it did. And we were able to clearly see this effect."

Udrescu compares the sensitivity of the measurements to being able to see how Mount Everest, placed on the surface of the sun, could, however minutely, change the sun's radius. By comparison, seeing certain effects of symmetry violation would be like seeing how the width of a single human hair would alter the sun's radius.

The results demonstrate that radioactive molecules such as RaF are ultrasensitive to nuclear effects and that their sensitivity may likely reveal more subtle, never-before-seen effects, such as tiny symmetry-violating nuclear properties, that could help to explain the universe's matter-antimmater asymmetry.

"These very heavy radioactive molecules are special and have sensitivity to nuclear phenomena that we cannot see in other molecules in nature," Udrescu says. "This shows that, when we start to search for symmetry-violating effects, we have a high chance of seeing them in these molecules."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Cancer screenings rebounded in 2020 after COVID but racial disparities remain

2021-07-07

BOSTON - The numbers of cancer screening tests rebounded sharply in the last quarter of 2020, following a dramatic decline in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, at one large hospital system in the Northeastern United States. These findings were released in a study published in Cancer Cell. The research also found an increase in racial and socioeconomic disparities among users of some screening tests during the pandemic.

Study co-senior author Toni K. Choueiri, MD, director of the Lank Center for Genitourinary Oncology at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, said following a dramatic decline during the first pandemic peak, there was a "substantial increase in screening procedures during the more recent periods ...

Researchers detail the most ancient bat fossil ever discovered in Asia

2021-07-07

LAWRENCE -- A new paper appearing in Biology Letters describes the oldest-known fragmentary bat fossils from Asia, pushing back the evolutionary record for bats on that continent to the dawn of the Eocene and boosting the possibility that the bat family's "mysterious" origins someday might be traced to Asia.

A team based at the University of Kansas and China performed the fieldwork in the Junggar Basin -- a very remote sedimentary basin in northwest China -- to discover two fossil teeth belonging to two separate specimens of the bat, dubbed Altaynycteris aurora.

The new fossil specimens help scientists better understand ...

Next generation cytogenetics is on its way

2021-07-07

Dutch-French research shows that Optical Genome Mapping (OGM) detects abnormalities in chromosomes and DNA very quickly, effectively and accurately. Sometimes even better than all existing techniques together, as they describe in two proof-of-concept studies published in the American Journal of Human Genetics. This new technique could radically change the existing workflow within cytogenetic laboratories.

Human hereditary material is stored in 46 chromosomes (23 pairs). Although those chromosomes are quite stable, changes in number or structure can still occur. A well-known example is Down syndrome, which is caused by an extra ...

Change in respiratory care strategies for preterm infants improves health outcomes

2021-07-07

A decade's worth of data shows that neonatologists are shifting the type of respiratory support they utilize for preterm infants, a move that could lead to improved health outcomes.

Using two large national datasets that included more than 1 million preterm infants, researchers in a new Vanderbilt-led study found that from 2008 to 2018 there was a greater than 10% decrease in the use of mechanical ventilation for this patient population. Concurrently, there was a similar increase in the use of non-invasive respiratory support, such as continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), for these infants.

The ...

New computational technique, software identifies cell types within a tumor and its microenvironment

2021-07-07

(Boston)--The discovery of novel groups or categories within diseases, organisms and biological processes and their organization into hierarchical relationships are important and recurrent pursuits in biology and medicine, which may help elucidate group-specific vulnerabilities and ultimately novel therapeutic interventions.

Now a new study introduces a novel computational methodology and an associated software tool called K2Taxonomer, which support the automated discovery and annotation of molecular classifications at multiple levels of resolution from high-throughput bulk and single cell 'omics' data. The study includes a case ...

The Obesity Society issues new position statement:

2021-07-07

SILVER SPRING, Md.--Vaccines such as Pfizer, Moderna, Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca are designed to prevent severe Coronavirus-19 Disease (COVID-19) due to acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and are highly efficacious. The efficacy is not different in people with and without obesity except for AstraZeneca which is not known, according to a new position statement from The Obesity Society (TOS), the leading scientific membership organization advancing the science-based understanding of the causes, consequences, prevention and treatment of obesity.

Trials have demonstrated high efficacy in individuals ...

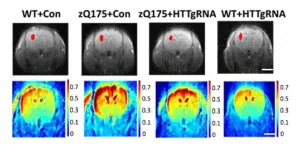

Gene therapy in early stages of Huntington's disease may slow down symptom progression

2021-07-07

In a new study on mice, Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers report that using MRI scans to measure blood volume in the brain can serve as a noninvasive way to potentially track the progress of gene editing therapies for early-stage Huntington's disease, a neurodegenerative disorder that attacks brain cells. The researchers say that by identifying and treating the mutation known to cause Huntington's disease with this type of gene therapy, before a patient starts showing symptoms, it may slow progression of the disease.

The findings of the study were published May 27 in the journal Brain.

"What's exciting about this study is the opportunity to identify a reliable biomarker that can ...

McMaster researchers identify how VITT happens

2021-07-07

Hamilton, ON (July 7, 2021) - A McMaster University team of researchers recently discovered how, exactly, the COVID-19 vaccines that use adenovirus vectors trigger a rare but sometimes fatal blood clotting reaction called vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia or VITT.

The findings will put scientists on the path of finding a way to better diagnose and treat VITT, possibly prevent it and potentially make vaccines safer.

The researchers' article was fast-tracked for publication today by the prestigious journal Nature in its accelerated article preview because of the importance of the research.

"Our work also answers important ...

New generation anti-cancer drug shows promise for children with brain tumours

2021-07-07

A genetic map of an aggressive childhood brain tumour called medulloblastoma has helped researchers identify a new generation anti-cancer drug that can be repurposed as an effective treatment for the disease.

This international collaboration, led by researchers from The University of Queensland's (UQ) Diamantina Institute and WEHI in Melbourne, could give parents hope in the fight against the most common and fatal brain cancer in children.

UQ lead researcher Dr Laura Genovesi said the team had mapped the genetics of these aggressive brain tumours for five ...

Not only humans got talent, dogs got it too!

2021-07-07

Some exceptionally gifted people have marked human history and culture. Leonardo, Mozart, and Einstein are some famous examples of this phenomenon.

Is talent in a given field a uniquely human phenomenon? We do not know whether gifted bees or elephants exist, just to name a few species, but now there is evidence that talent in a specific field exists, in at least one non-human species: the dog.

A new study, just published in Scientific Reports, found that, while the vast majority of dogs struggle to learn object labels (such as the names of their toys), when tested in strictly controlled conditions, a handful of gifted word learner ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Low-temperature-activated deployment of smart 4D-printed vascular stents

Clinical relevance of brain functional connectome uniqueness in major depressive disorder

For dementia patients, easy access to experts may help the most

YouTubers love wildlife, but commenters aren't calling for conservation action

New study: Immune cells linked to Epstein-Barr virus may play a role in MS

AI tool predicts brain age, cancer survival, and other disease signals from unlabeled brain MRIs

Peak mental sharpness could be like getting in an extra 40 minutes of work per day, study finds

No association between COVID-vaccine and decrease in childbirth

AI enabled stethoscope demonstrated to be twice as efficient at detecting valvular heart disease in the clinic

Development by Graz University of Technology to reduce disruptions in the railway network

Large study shows scaling startups risk increasing gender gaps

Scientists find a black hole spewing more energy than the Death Star

A rapid evolutionary process provides Sudanese Copts with resistance to malaria

Humidity-resistant hydrogen sensor can improve safety in large-scale clean energy

Breathing in the past: How museums can use biomolecular archaeology to bring ancient scents to life

Dementia research must include voices of those with lived experience

Natto your average food

Family dinners may reduce substance-use risk for many adolescents

Kumamoto University Professor Kazuya Yamagata receives 2025 Erwin von Bälz Prize (Second Prize)

Sustainable electrosynthesis of ethylamine at an industrial scale

A mint idea becomes a game changer for medical devices

Innovation at a crossroads: Virginia Tech scientist calls for balance between research integrity and commercialization

Tropical peatlands are a major source of greenhouse gas emissions

From cytoplasm to nucleus: A new workflow to improve gene therapy odds

Three Illinois Tech engineering professors named IEEE fellows

Five mutational “fingerprints” could help predict how visible tumours are to the immune system

Rates of autism in girls and boys may be more equal than previously thought

Testing menstrual blood for HPV could be “robust alternative” to cervical screening

Are returning Pumas putting Patagonian Penguins at risk? New study reveals the likelihood

Exposure to burn injuries played key role in shaping human evolution, study suggests

[Press-News.org] New clues to why there's so little antimatter in the universeRadioactive molecules are sensitive to subtle nuclear phenomena and might help physicists probe the violation of the most fundamental symmetries of nature.