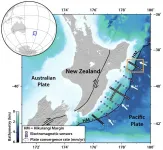

(Press-News.org) The Hikurangi Margin, located off the east coast of the North Island of New Zealand, is where the Pacific tectonic plate dives underneath the Australian tectonic plate, in what scientists call a subduction zone. This interface of tectonic plates is partly responsible for the more than 15,000 earthquakes the region experiences each year. Most are too small to be noticed, but between 150 and 200 are large enough to be felt. Geological evidence suggests that large earthquakes happened in the southern part of the margin before human record-keeping began.

Geophysicists, geologists, and geochemists from throughout the world have been working together to understand why this plate boundary behaves as it does, producing both imperceptible silent earthquakes, but also potentially major ones. A study published today in the journal Nature offers new perspective and possible answers.

Scientists knew that the ocean floor at the northern part of the island, where the plates slide slowly together, generates the small, slow-moving earthquakes called slow slip events--movements that take weeks, sometimes months to complete. But at the southern end of the island, instead of sliding slowly as they do in the northern area, the tectonic plates lock. This locking sets up the conditions for a sudden release of the plates, which can trigger a large earthquake.

"It is really curious and not understood why, in a relatively small geographic area, you would go from lots of small, slow-moving earthquakes to a potential for a really large earthquake," said marine electromagnetic geophysicist Christine Chesley, a graduate student at Columbia University's Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and lead author on the new paper. "That's what we've been trying to understand, the difference in this margin."

In December 2018, a research team began a 29-day deep-sea cruise to collect data. Similar to taking an MRI of the Earth, the team employed electromagnetic wave energy to measure how current moves through features in the ocean floor. From these data, the team was able to get a more precise look at the role seamounts, large undersea mountains, play in generating earthquakes.

"The northern part of the margin has really large seamounts. It had been unclear what those mountains can do when they subduct (dive down into the deep earth) and how that dynamic affects the interaction between the two plates," said Chesley.

It turns out, the seamounts hold a lot more water than geophysicists had expected -- about three to five times more than typical oceanic crust. The abundant water lubricates the plates where they join, helping to smooth any slippage, and preventing the plates from the sticking that can set up a large earthquake. This helps explain the tendency toward the slow, silent earthquakes at the northern end of the margin.

Using these data, Chesley and her colleagues were also able to closely examine what is happening as a seamount subducts. They discovered an area in the upper plate that seems to be damaged by a subducting seamount. This upper plate zone also seemed to have more water in it.

"That suggests the seamount is breaking up the upper plate, making it weaker, which helps explain the unusual pattern of silent earthquakes there," said Chesley. The example provides another indication of how seamounts influence tectonic behavior and earthquake hazards.

Conversely, the lack of lubrication and the weakening effects of seamounts may make the southern part of the island more prone to sticking and generating large earthquakes.

Chesley, who is on track to complete her Ph.D. in the fall, hopes that these findings will encourage researchers to consider the way water in these seamounts contributes to seismic behavior as they continue to work to understand slow-moving earthquakes. "The more we study earthquakes, the more it seems water plays a starring role in modulating slip on faults," said Chesley. "Understanding when and where water is input into the system can only improve natural hazard assessment efforts."

INFORMATION:

Samer Naif, former Lamont Assistant Research Professor, now assistant professor at Georgia Tech; Kerry Key, associate professor at Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory; and Dan Bassett, research scientist at GNS Science, collaborated on this research. This project was funded by the National Science Foundation.

Scientist contacts:

Christine Chesley: chesley@ldeo.columbia.edu

Kerry Key: kkey@ldeo.columbia.edu

More information:

Kevin Krajick, Senior editor, science news, The Earth Institute

kkrajick@ei.columbia.edu 212-854-9729

The Earth Institute, Columbia University mobilizes the sciences, education and public policy to achieve a sustainable earth. http://www.earth.columbia.edu.

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory is Columbia University's home for Earth science research. Its scientists develop fundamental knowledge about the origin, evolution and future of the natural world, from the planet's deepest interior to the outer reaches of its atmosphere, on every continent and in every ocean, providing a rational basis for the difficult choices facing humanity. http://www.ldeo.columbia.edu | @LamontEarth

Reston, VA--For patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAC), molecular imaging can improve staging and clinical management of the disease, according to research published in the June issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine. In a retrospective study of PDAC patients, the addition of PET/CT imaging with 68Ga-FAPI led to restaging of disease in more than half of the patients, most notably in those with local recurrence.

PDAC is a highly lethal cancer, with a five-year survival rate of less than 10 percent. Optimal imaging of PDAC is crucial for accurate initial TNM (tumor, node, metastases) staging and selection ...

Dancing with music can halt most debilitating symptoms of Parkinson's disease

First-of-its-kind York U study shows participating in weekly dance training improves daily living and motor function for those with mild-to-moderate Parkinson's

TORONTO, July 7, 2021 - A new study published in Brain Sciences today, shows patients with mild-to-moderate Parkinson's disease (PD) can slow the progress of the disease by participating in dance training with music for one-and-a-quarter hours per week. Over the course of three years, this activity was found to reduce daily motor issues such as those related to balance and speech, ...

When a head of state or government official travels to another country to meet with his/her counterpart, the high-level visit often entails a range of public diplomacy activities, which aim to increase public support in the host country. These activities often include events such as hosting a joint press conference, attending a reception or dinner, visiting a historic site, or attending a social or sports event. A new study finds that public diplomacy accompanying a high-level visit by a national leader increases public approval in the host country. The findings are published in the American Political ...

The Arctic is warming at approximately twice the global rate. A new study led by researchers from McGill University finds that cold-adapted Arctic species, like the thick-billed murre, are especially vulnerable to heat stress caused by climate change.

"We discovered that murres have the lowest cooling efficiency ever reported in birds, which means they have an extremely poor ability to dissipate or lose heat," says lead author Emily Choy, a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Natural Resource Sciences Department at McGill University.

Following reports of the seabirds dying in their nests on sunny days, the researchers trekked the cliffs ...

Data from nine cities in Mexico confirms that identifying dengue fever “hot spots” can provide a predictive map for future outbreaks of Zika and chikungunya. All three of these viral diseases are spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Lancet Planetary Health published the research, led by Gonzalo Vazquez-Prokopec, associate professor in Emory University’s Department of Environmental Sciences. The study provides a risk-stratification method to more effectively guide the control of diseases spread by Aedes aegypti. “Our results can help public health officials to do targeted, proactive interventions ...

Prostate cancer is the most diagnosed cancer and a leading cause of death by cancer in Australian men.

Early detection is key to successful treatment but men often dodge the doctor, avoiding diagnosis tests until it's too late.

Now an artificial intelligence (AI) program developed at RMIT University could catch the disease earlier, allowing for incidental detection through routine computed tomography (CT) scans.

The tech, developed in collaboration with clinicians at St Vincent's Hospital Melbourne, works by analysing CT scans for tell-tale signs of prostate ...

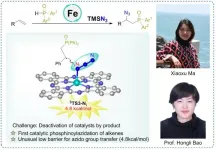

Phosphinoylazidation of alkenes is a direct method to build nitrogen- and phosphorus-containing compounds from feedstock chemicals. Notwithstanding the advances in other phosphinyl radical related difunctionalization of alkenes, catalytic phosphinoylazidation of alkenes has not yet been reported. Thus, efficient access to organic nitrogen and phosphorus compounds, and making the azido group transfer more feasible to further render this step more competitive remain challenging.

Recently, a research team led by Prof. Hongli Bao from Fujian Institute of Research on the Structure of Matter, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) reported the first iron-catalyzed phosphinoylazidation of alkenes under ...

The growing rate of ice melt in the Arctic due to rising global temperatures has opened up the Northwest Passage (NWP) to more ship traffic, increasing the potential risk of an oil spill and other environmental disasters. A new study published in the journal Risk Analysis suggests that an oil spill in the Canadian Arctic could be devastating--especially for vulnerable indigenous communities.

"Infrastructure along the NWP in Canada's Arctic is almost non-existent. This presents major challenges to any response efforts in the case of a natural disaster," says Mawuli Afenyo, lead author, University of Manitoba researcher, and expert on the risks of Arctic shipping.

Afenyo and his colleagues have developed a new ...

(Boston)--High-risk neuroblastoma is an aggressive childhood cancer with poor treatment outcomes. Despite intensive chemotherapy and radiotherapy, less than 50 percent of these children survive for five years. While the genetics of human neuroblastoma have been extensively studied, actionable therapeutics are limited.

Now researchers in the Feng lab at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM), in collaboration with scientists in the Simon lab at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn), have not only discovered why this cancer is so aggressive but also reveal a promising therapeutic approach to treat these patients. These findings appear online in the journal Cancer Research, a journal ...

An international research team has found that despite being the world's leading cause of pain, disability and healthcare expenditure, the prevention and management of musculoskeletal health, including conditions such as low back pain, fractures, arthritis and osteoporosis, is globally under-prioritised and have devised an action plan to address this gap.

Project lead, Professor Andrew Briggs from Curtin University said more than 1.5 billion people lived with a musculoskeletal condition in 2019, which was 84 per cent more than in 1990, and despite many 'calls to action' and an ever-increasing ageing population, health systems continue to ...