Arctic seabirds are less heat tolerant, more vulnerable to climate change

Arctic species poorly adapted for coping with rising temperatures as the Arctic continues to warm

2021-07-07

(Press-News.org) The Arctic is warming at approximately twice the global rate. A new study led by researchers from McGill University finds that cold-adapted Arctic species, like the thick-billed murre, are especially vulnerable to heat stress caused by climate change.

"We discovered that murres have the lowest cooling efficiency ever reported in birds, which means they have an extremely poor ability to dissipate or lose heat," says lead author Emily Choy, a Postdoctoral Fellow in the Natural Resource Sciences Department at McGill University.

Following reports of the seabirds dying in their nests on sunny days, the researchers trekked the cliffs of Coast Island in northern Hudson Bay to study a colony of 30,000 breeding pairs. They put the birds' heat tolerance to the test and found that the animals showed signs of stress at temperatures as low as 21C.

Until now few studies have explored the direct effects of warming temperatures on Arctic wildlife. The study, published in Journal of Experimental Biology, is the first to examine heat stress in large Arctic seabirds.

Bigger not always better

By measuring breathing rates and water loss as the murres were subjected to increasing temperatures, the researchers found that larger birds were more sensitive to heat stress than smaller birds.

Weighing up to one kilogram, murres have a very high metabolic rate relative to their size, meaning when they pant or flap their wings to cool off, they expend a very high amount of energy, producing even more heat.

These seabirds nest in dense colonies, often breeding shoulder to shoulder along the narrow ledges of cliffs. Male and female birds take turns nesting on 12-hour shifts. According to the researchers, the thick-billed murres' limited heat tolerance may explain their mortalities on warm weather days.

"Overheating is an important and understudied effect of climate change on Arctic wildlife," says Choy. "Murres and potentially other Arctic species are poorly adapted for coping with warming temperatures, which is important as the Arctic continues to warm."

INFORMATION:

About this study

"Limited heat tolerance in a cold-adapted seabird: implications of a warming Arctic" by Emily Choy, Ryan O'Connor, Grant Gilchrist, Anna Hargreaves, Oliver Love, Francois Vezina, and Kyle Elliott was published in the Journal of Experimental Biology.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1242/jeb.242168

About McGill University

Founded in 1821, McGill University is home to exceptional students, faculty, and staff from across Canada and around the world. It is consistently ranked as one of the top universities, both nationally and internationally. It is a world-renowned institution of higher learning with research activities spanning two campuses, 11 faculties, 13 professional schools, 300 programs of study and over 40,000 students, including more than 10,200 graduate students.??

McGill's commitment to sustainability reaches back several decades and spans scales from local to global. The sustainability declarations that we have signed affirm our role in helping to shape a future where people and the planet can flourish.

https://www.mcgill.ca/newsroom/

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-07

Data from nine cities in Mexico confirms that identifying dengue fever “hot spots” can provide a predictive map for future outbreaks of Zika and chikungunya. All three of these viral diseases are spread by the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Lancet Planetary Health published the research, led by Gonzalo Vazquez-Prokopec, associate professor in Emory University’s Department of Environmental Sciences. The study provides a risk-stratification method to more effectively guide the control of diseases spread by Aedes aegypti. “Our results can help public health officials to do targeted, proactive interventions ...

2021-07-07

Prostate cancer is the most diagnosed cancer and a leading cause of death by cancer in Australian men.

Early detection is key to successful treatment but men often dodge the doctor, avoiding diagnosis tests until it's too late.

Now an artificial intelligence (AI) program developed at RMIT University could catch the disease earlier, allowing for incidental detection through routine computed tomography (CT) scans.

The tech, developed in collaboration with clinicians at St Vincent's Hospital Melbourne, works by analysing CT scans for tell-tale signs of prostate ...

2021-07-07

Phosphinoylazidation of alkenes is a direct method to build nitrogen- and phosphorus-containing compounds from feedstock chemicals. Notwithstanding the advances in other phosphinyl radical related difunctionalization of alkenes, catalytic phosphinoylazidation of alkenes has not yet been reported. Thus, efficient access to organic nitrogen and phosphorus compounds, and making the azido group transfer more feasible to further render this step more competitive remain challenging.

Recently, a research team led by Prof. Hongli Bao from Fujian Institute of Research on the Structure of Matter, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) reported the first iron-catalyzed phosphinoylazidation of alkenes under ...

2021-07-07

The growing rate of ice melt in the Arctic due to rising global temperatures has opened up the Northwest Passage (NWP) to more ship traffic, increasing the potential risk of an oil spill and other environmental disasters. A new study published in the journal Risk Analysis suggests that an oil spill in the Canadian Arctic could be devastating--especially for vulnerable indigenous communities.

"Infrastructure along the NWP in Canada's Arctic is almost non-existent. This presents major challenges to any response efforts in the case of a natural disaster," says Mawuli Afenyo, lead author, University of Manitoba researcher, and expert on the risks of Arctic shipping.

Afenyo and his colleagues have developed a new ...

2021-07-07

(Boston)--High-risk neuroblastoma is an aggressive childhood cancer with poor treatment outcomes. Despite intensive chemotherapy and radiotherapy, less than 50 percent of these children survive for five years. While the genetics of human neuroblastoma have been extensively studied, actionable therapeutics are limited.

Now researchers in the Feng lab at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM), in collaboration with scientists in the Simon lab at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania (Penn), have not only discovered why this cancer is so aggressive but also reveal a promising therapeutic approach to treat these patients. These findings appear online in the journal Cancer Research, a journal ...

2021-07-07

An international research team has found that despite being the world's leading cause of pain, disability and healthcare expenditure, the prevention and management of musculoskeletal health, including conditions such as low back pain, fractures, arthritis and osteoporosis, is globally under-prioritised and have devised an action plan to address this gap.

Project lead, Professor Andrew Briggs from Curtin University said more than 1.5 billion people lived with a musculoskeletal condition in 2019, which was 84 per cent more than in 1990, and despite many 'calls to action' and an ever-increasing ageing population, health systems continue to ...

2021-07-07

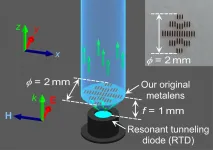

Screens may be larger on smartphones now, but nearly every other component is designed to be thinner, flatter and tinier than ever before. The engineering requires a shift from shapely, and bulky lenses to the development of miniaturized, two-dimensional metalenses. They might look better, but do they work better?

A team of Japan-based researchers says yes, thanks to a solution they published on July 7th in Applied Physics Express, a journal of the Japan Society of Applied Physics.

The researchers previously developed a low-reflection metasurface -- an ultra-thin interface that can manipulate electromagnetic ...

2021-07-07

Researchers from IDIBELL and the University of Barcelona (UB) have described that neurons derived from Parkinson's patients show impairments in their transmission before neurodegeneration.

For this study, it has been used dopaminergic neurons differentiated from patient stem cells as a model.

Parkinson's is a neurodegenerative disease characterized by the death of dopaminergic neurons. This neuronal death leads to a series of motor manifestations characteristic of the disease, such as tremors, rigidity, slowness of movement, or postural instability. In most cases, the cause of the disease is unknown, however, mutations in the LRRK2 gene are responsible for 5% of cases.

Current therapies against Parkinson's are focus on alleviating the symptoms but do not stop its progression. It ...

2021-07-07

Scientists at the University of Southampton have discovered that changes in Earth's orbit may have allowed complex life to emerge and thrive during the most hostile climate episode the planet has ever experienced.

The researchers - working with colleagues in the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Curtin University, University of Hong Kong, and the University of Tübingen - studied a succession of rocks laid down when most of Earth's surface was covered in ice during a severe glaciation, dubbed 'Snowball Earth', that lasted over 50 million years. Their findings are published in the journal Nature Communications.

"One ...

2021-07-07

By combining two distinct approaches into an integrated workflow, Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD) researchers have developed a novel automated process for designing and fabricating customised soft robots. Their method, published in Advanced Materials Technologies, can be applied to other kinds of soft robots--allowing their mechanical properties to be tailored in an accessible manner.

Though robots are often depicted as stiff, metallic structures, an emerging class of pliable machines known as soft robots is rapidly gaining traction. ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Arctic seabirds are less heat tolerant, more vulnerable to climate change

Arctic species poorly adapted for coping with rising temperatures as the Arctic continues to warm