(Press-News.org) Ever since the 1986 discovery that copper oxide materials, or cuprates, could carry electrical current with no loss at unexpectedly high temperatures, scientists have been looking for other unconventional superconductors that could operate even closer to room temperature. This would allow for a host of everyday applications that could transform society by making energy transmission more efficient, for instance.

Nickel oxides, or nickelates, seemed like a promising candidate. They're based on nickel, which sits next to copper on the periodic table, and the two elements have some common characteristics. It was not unreasonable to think that superconductivity would be one of them.

But it took years of trying before scientists at the Department of Energy's SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and Stanford University finally created the first nickelate that showed clear signs of superconductivity.

Now SLAC, Stanford and Diamond Light Source researchers have made the first measurements of magnetic excitations that spread through the new material like ripples in a pond. The results reveal both important similarities and subtle differences between nickelates and cuprates. The scientists published their results in Science today.

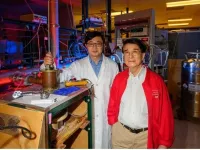

"This is exciting, because it gives us a new angle for exploring how unconventional superconductors work, which is still an open question after 30-plus years of research," said

Haiyu Lu, a Stanford graduate student who did the bulk of the research with Stanford postdoctoral researcher Matteo Rossi and SLAC staff scientist Wei-Sheng Lee.

"Among other things," he said, "we want to understand the nature of the relationship between cuprates and nickelates: Are they just neighbors, waving hello and going about their separate ways, or more like cousins who share family traits and ways of doing things?"

The results of this study, he said, add to a growing body of evidence that their relationship is a close one.

Spins in a checkerboard

Cuprates and nickelates have similar structures, with their atoms arranged in a rigid lattice. Both come in thin, two-dimensional sheets that are layered with other elements, such as rare-earth ions. These thin sheets become superconducting when they're cooled below a certain temperature and the density of their free-flowing electrons is adjusted in a process known as doping.

The first superconducting nickelate was discovered in 2019 at SLAC and Stanford. Last year, the same SLAC/Stanford team that performed this latest experiment published the first detailed study of the nickelate's electronic behavior. That study established that in undoped nickelate, electrons flow freely in nickel oxide layers, but electrons from the intervening layers also contribute electrons to the flow. This creates a 3D metallic state that's quite different from what is seen in cuprates, which are insulators when undoped.

Magnetism is also important in superconductivity. It's created by the spins of a material's electrons. When they're all oriented in the same direction, either up or down, the material is magnetic in the sense that it could stick to the door of your fridge.

Cuprates, on the other hand, are antiferromagnetic: Their electron spins form a checkerboard pattern, so each down spin is surrounded by up spins and vice versa. The alternating spins cancel each other out, so the material as a whole is not magnetic in the ordinary sense.

Would nickelate have those same characteristics? To find out, researchers took samples of it to the Diamond Light Source synchrotron in the UK for examination with resonant inelastic X-ray scattering, or RIXS. In this technique, scientists scatter X-ray light off a sample of material. This injection of energy creates magnetic excitations - ripples that travel through the material and randomly flip the spins of some of its electrons. RIXS allows scientists to measure very weak excitations that couldn't be observed otherwise.

Creating new recipes

"What we find is quite interesting," Lee said. "The data show that nickelate has the same type of antiferromagnetic interaction that cuprates have. It also has a similar magnetic energy, which reflects the strength of the interactions between neighboring spins that keep this magnetic order in place. This implies that the same type of physics is important in both."

But there are also differences, Rossi noted. Magnetic excitations don't spread as far in nickelates, and die out more quickly. Doping also affects the two materials differently; the positively charged "holes" it creates are concentrated around nickel atoms in nickelates and around oxygen atoms in cuprates, and this affects how their electrons behave.

As this work continues, Rossi said, the team will test how doping the nickelate in various ways and swapping different rare earth elements into the layers between the nickel oxide sheets affect the material's superconductivity - paving the way, they hope, to discovery of better superconductors.

INFORMATION:

Lu, Rossi, Lee and six other members of the research team are investigators with the Stanford Institute for Materials and Energy Sciences (SIMES) at SLAC, which received major funding from the DOE Office of Science. Researchers from the Lorentz Institute for Theoretical Physics at Leiden University in the Netherlands also contributed to this work.

Citation: Haiyu Lu et al., Science, 9 July 2021 (10.1126/science.abd7726)

SLAC is a vibrant multiprogram laboratory that explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by scientists around the globe. With research spanning particle physics, astrophysics and cosmology, materials, chemistry, bio- and energy sciences and scientific computing, we help solve real-world problems and advance the interests of the nation.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.

Conditions in the tropical ocean affect weather patterns worldwide. The most well-known examples are El Niño or La Niña events, but scientists believe other key elements of the tropical climate remain undiscovered.

In a study recently published in Geophysical Research Letters, scientists from the University of Washington and NOAA's Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory use remotely-piloted sailboats to gather data on cold air pools, or pockets of cooler air that form below tropical storm clouds.

"Atmospheric cold pools are cold air masses that flow outward beneath intense thunderstorms and alter the surrounding environment," ...

In a critical next step toward room-temperature superconductivity at ambient pressure, Paul Chu, Founding Director and Chief Scientist at the Texas Center for Superconductivity at the University of Houston (TcSUH), Liangzi Deng, research assistant professor of physics at TcSUH, and their colleagues at TcSUH conceived and developed a pressure-quench (PQ) technique that retains the pressure-enhanced and/or -induced high transition temperature (Tc) phase even after the removal of the applied pressure that generates this phase.

Pengcheng Dai, professor of physics and astronomy at Rice University and his group, and Yanming Ma, Dean of the College of Physics ...

The Large High Altitude Air Shower Observatory (LHAASO), one of China's key national science and technology infrastructure facilities, has accurately measured the brightness over 3.5 orders of magnitude of the standard candle in high-energy astronomy, thus calibrating a new standard for ultra-high-energy (UHE) gamma-ray sources. The standard candle is the famous Crab Nebula, which evolved from the "guest star" recorded by the imperial astronomers of China's Song Dynasty.

LHAASO has also discovered a photon with an energy of 1.1 PeV (1 PeV = one quadrillion electronvolts), indicating the presence of an extremely powerful electron accelerator--about one-tenth the size of the solar system--located in the core ...

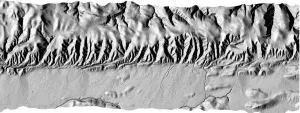

As tectonic plates slip past each other, the rivers that cross fault lines change shape. The shifting ground stretches the river channels until the water breaks its course and flows onto new paths.

In a study published July 9 in Science, researchers at UC Santa Cruz created a model that helps predict this process. It provides broad context to how rivers and faults interact to shape the nearby topography.

The group originally planned to use the San Andreas fault in the Carrizo Plain of California to study how fault movement shapes the landscapes near rivers. But after spending hours pouring over aerial imagery and remote topographic data, their understanding of how the terrain evolves began to change. They realized that rivers play a more active ...

For the first time, Princess Margaret researchers have mapped out where and how leukemia begins and develops in infants with Down syndrome in preclinical models, paving the way to potentially prevent this cancer in the future.

Children with Down syndrome have a 150-fold increased risk of developing myeloid leukemia within the first five years of their life. Yet the mechanism by which the extra copy of chromosome 21 predisposes to leukemia remains unclear.

Down syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by a random error in cell division in early human development that results in an extra copy of chromosome 21. This extra copy is what causes the developmental changes and physical ...

Proactive, frequent rapid testing of all students for COVID-19 is more effective at preventing large transmission clusters in schools than measures that are only initiated when someone develops symptoms and then tests positive, Simon Fraser University researchers have found. Professors Caroline Colijn and Paul Tupper used a mathematical model to simulate COVID-19's spread in the classroom and published their research results today in the journal PLOS Computational Biology.

The simulations showed that, in a classroom with 25 students, anywhere from zero to 20 students might be infected after exposure, depending on even small adjustments ...

(BOSTON) -- Current clinical interventions for infectious diseases are facing increasing challenges due to the ever-rising number of drug-resistant microbial infections, epidemic outbreaks of pathogenic bacteria, and the continued possibility of new biothreats that might emerge in the future. Effective vaccines could act as a bulwark to prevent many bacterial infections and some of their most severe consequences, including sepsis. According to the END ...

Feeling anxious about health, family or money is normal for most people--especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. But for those with anxiety disorders, these everyday worries tend to heighten even when there is little or no reason to be concerned.

Researchers from Indiana University School of Medicine recently studied the behaviors associated with anxiety--published in Psychopharmacology--examining how biological factors impact anxiety disorders, specifically in females. They found that anxiety in females intensifies when there's a specific, life-relevant condition.

The team, led by Thatiane De Oliveira Sergio, PhD, postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Woody Hopf, PhD, professor of ...

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual Veterans from the Vietnam era report PTSD and poorer mental health more often than their heterosexual counterparts, according to an analysis of data from the Vietnam Era Health Retrospective Observational Study (VE-HEROeS).

A greater burden of potentially traumatic events among LGB Veterans, such as childhood physical abuse, adult physical assault, and sexual assault, was associated with the differences.

"This study is the first to document sexual orientation differences in trauma experiences, probable PTSD, and health-related quality of life in LGB Veterans using a nationally representative sample," said Dr. John Blosnich, ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - Placing rodent traps and bait stations based on rat and mouse behavior could protect the food supply more effectively than the current standard of placing them set distances apart, according to new research from Cornell University.

Rodents cause billions of dollars in losses to the food supply each year, and carry pathogens that can sicken and kill humans, including salmonella, E. coli and Leptospira.

In the 1940s and 50s, scientists recommended that farmers, food manufacturers and distributors evenly space rodent traps or bait boxes in their facilities. But in fact, a new study finds placement based on rat and mouse behavior is more effective.

"From there, it just became a mantra without anybody scientifically evaluating it to see whether this ...