(Press-News.org) Contrary to conventional thought, songbirds can taste sugar--even though songbirds are the descendants of meat-eating dinosaurs and are missing a key protein that allows humans and many other animals to taste sweetness. An international team investigated how many bird species can taste sweet and how far back that ability evolved. Their work was published today in the journal Science.

The researchers offered two species of songbirds a choice between sugar water and plain water--nectar-taking honeyeaters, as well as canaries, a grain-eating bird not known for consuming sweet foods. They also examined taste receptor responses sampled from a variety of other species. Regardless of whether their main diet consisted of seeds, grains, or insects, songbird taste receptors responded to sugars.

"This was a clear hint that we should concentrate on a range of songbirds, not only the nectar-specialized ones, when searching for the origins of avian sweet taste," explains senior author Maude Baldwin at the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology in Germany. Baldwin led this study with Yasuka Toda from Meiji University in Japan.

Sugar is a vital carbohydrate providing lots of energy and may have had far-reaching effects on songbird evolution. Though it is thought that most bird lineages can't taste sweetness at all, the scientists now believe that songbirds, which account for more than 40% of the world's bird species, can actually taste sweet, and that sugary food sources may have contributed to their success.

Baldwin and Toda dug down to the molecular level to understand the modifications to the "umami" taste receptor that enabled sweet perception among songbirds.

"Because sugar detection is complex, we needed to analyze more than one hundred receptor variants to reveal the molecular mechanisms underlying the sugar responses," says Toda. These exact changes coincide only slightly with those seen in the distantly-related hummingbirds, even though similar areas of the receptor are modified.

Though songbirds evolved similar workarounds to taste sweetness, they did so at different times, in different places, and in slightly different ways--an example of "convergent evolution." Some songbirds, such as honeyeaters, sunbirds, honeycreepers, and flowerpiercers are now just as dependent on nectar as the hummingbirds.

"This study fundamentally changes the way we think about the sensory perceptions of nearly half the world's birds," says study co-author Eliot Miller at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. "It demonstrates that most songbirds definitely can taste sweet and got there by following nearly the same evolutionary path that hummingbirds did--it's a neat story about how convergence happens."

Exploring the songbird family tree, the researchers conclude that songbirds evolved to sense sweetness approximately 30 million years ago, before the early ancestors of songbirds left Australia, where all songbirds originated. Even after songbirds radiated across the world, they kept their ability to taste sugar.

Researchers in Japan, Germany, the United States, Hong Kong, and Australia participated in this study. Future studies will explore how sweet perception has coevolved with other physiological traits, such as changes in digestion and metabolism, across bird evolution.

INFORMATION:

A team of physicists from the Harvard-MIT Center for Ultracold Atoms and other universities has developed a special type of quantum computer known as a programmable quantum simulator capable of operating with 256 quantum bits, or "qubits."

The system marks a major step toward building large-scale quantum machines that could be used to shed light on a host of complex quantum processes and eventually help bring about real-world breakthroughs in material science, communication technologies, finance, and many other fields, overcoming research hurdles that are beyond the capabilities of even the fastest supercomputers today. Qubits are the fundamental building blocks on which quantum computers ...

How does unicellular life transition to multicellular life? The research team of Professor Lutz Becks at the Limnological Institute of the University of Konstanz has taken a major step forward in explaining this very complex process. They were able to demonstrate - in collaboration with a colleague from the Alfred Wegner Institute (AWI) - that the unicellular green algae Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, over only 500 generations, develops mutations that provide the first step towards multicellular life. This experimentally confirmed a theory on the origin of multicellular life, which says that the evolution of cell groups and the subsequent steps towards multicellularity can only take place when cell groups are both better at reproduction and more likely to survive than single cells. ...

Although the giant panda is in practice a herbivore, its masticatory system functions differently from the other herbivores. Through the processes of natural selection, the giant panda's dietary preference has strongly impacted the evolution of its teeth and jaws. Researchers from the Institute of Dentistry at the University of Turku and the Biodiversity unit of the University of Turku together with researchers from the China Conservation and Research Center for Giant Panda (CCRCGP) have been the first in the world to solve the mystery of how the giant panda's special stomatognathic system functions.

The bamboo diet of the giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) has long been a ...

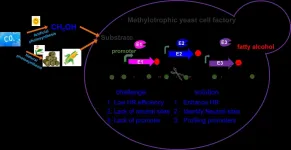

Pichia pastoris (syn. Komagataella phaffii), a model methylotrophic yeast, can easily achieve high density fermentation, and thus is considered as a promising chassis cell for efficient methanol biotransformation. However, inefficient gene editing and lack of synthetic biology tools hinder its metabolic engineering toward industrial application.

Recently, a research group led by Prof. ZHOU Yongjin from the Dalian Institute of Chemical Physics (DICP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences established an efficient genetic engineering platform in Pichia pastoris.

The study was published in Nucleic Acids Research on July 1.

The researchers developed ...

Depression has been treated traditionally with inhibitors of serotonin reuptake in the central nervous system. These drugs do not come without side effects, such as lack of immediate therapeutic action, the need for daily doses and the danger of becoming addicted to some of these drugs. That is why scientists continue to work on new therapies to treat depression.

In 2019, an international group of researchers co-led by Dr Yousef Tizabe from the Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, D.C., and Professor José Aguilera from the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and the Institut de Neurociències ...

To splice or not to splice...

In an article published in the journal RNA, Karan Bedi, a bioinformatician in Mats Ljungman's lab, Department of Radiation Oncology at the University of Michigan Medical School, investigated the efficiency of splicing across different human cell types. The results were surprising in that the splicing process appears to be quite inefficient, leaving most intronic sequences untouched as the transcripts are being synthesized. The study also reports variable patterns between the different introns within a gene and across cell lines, and it further highlights ...

Researchers at the University of Freiburg and the University of Stuttgart have developed a new process for producing movable, self-adjusting materials systems with standard 3D-printers. These systems can undergo complex shape changes, contracting and expanding under the influence of moisture in a pre-programmed manner. The scientists modeled their development based on the movement mechanisms of the climbing plant known as the air potato (Dioscorea bulbifera). With their new method, the team has produced its first prototype: a forearm brace that adapts to the wearer and which can be further developed for medical applications. ...

Recess quality, not just the amount of time spent away from the classroom, plays a major role in whether children experience the full physical, mental and social-emotional benefits of recess, a new study from Oregon State University found.

"Not all recess is created equal," said William Massey, study author and an assistant professor in OSU's College of Public Health and Human Sciences. With schools returning to full-time in-person classes this fall, he said, "Now is a good time to rethink, 'How do we create schools that are more child-friendly?' I think ensuring quality access to play time and space during the school day is a way we can do that." ...

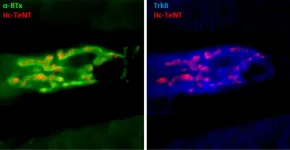

A research group including Kobe University's Professor TAKUMI Toru (also a Senior Visiting Scientist at RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research) and Assistant Professor TAMADA Kota, both of the Physiology Division in the Graduate School of Medicine, has revealed a causal gene (Necdin, NDN) in autism model mice that have the chromosomal abnormality (*1) called copy number variation (*2).

The researchers hope to illuminate the NDN gene's molecular mechanism in order to contribute towards the creation of new treatment strategies for developmental disorders including autism.

These research results were published in Nature Communications on July 1, 2021.

Main Points

The research ...

Although Covid-19 affects men and women differently, the large majority of current clinical studies of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19 makes no mention of sex/gender. Indeed, only a fraction, 4 percent, explicitly plan to address sex and gender in their analysis, concludes a new analysis of nearly 4,500 studies. 21 percent only take this variable into account when selecting participants while 5.4 % go as far as planning to have sex-matched or representative subgroups and samples. The article is published in Nature Communications.

During the corona pandemic, differences can be observed between men and women. Men are more vulnerable to a severe course of COVID-19; ...