(Press-News.org) Boosting the body's own disease-fighting immune pathway could provide answers in the desperate search for new treatments for tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis still represents an enormous global disease burden and is one of the top 10 causes of death worldwide.

Led by WEHI's Dr Michael Stutz and Professor Marc Pellegrini and published in Immunity, the study uncovered how cells infected with tuberculosis bacteria can die, and that using new medicines to enhance particular forms of cell death decreased the severity of the disease in a preclinical model.

At a glance

Researchers were able to demonstrate that cells infected with tuberculosis bacteria have functional apoptosis cell death pathways, and showed their importance in combatting severe disease.

Using preclinical models, researchers were able to pinpoint the critical apoptotic pathways as targets for new therapies, whereby infected cells can be killed by drugs called IAP inhibitors.

The study demonstrated that host-directed therapies were viable for infections such as tuberculosis, which is important in the era of extensive antibiotic resistance.

Fighting antibiotic resistance

Tuberculosis is caused by bacteria that infect the lungs, spreading from person to person through the air. A challenge in the fight against tuberculosis is that the bacteria that cause the disease have developed resistance to most antibiotic treatments, leading to a need for new treatment approaches.

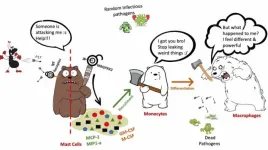

Tuberculosis bacteria grow within immune cells in the lungs. One of the ways that cells protect against these 'intracellular' pathogens is to undergo a form of cell death called apoptosis - destroying the cell as well as the microbes within it.

Using preclinical models, researchers sequentially deleted key apoptosis effectors, to demonstrate their roles in controlling tuberculosis infections. This demonstrated that a proportion of tuberculosis-infected cells could die by apoptosis - opening up new opportunities for controlling the disease.

Using host-directed therapies to reduce disease burden

Dr Stutz said researchers then tested new drugs that force cells to die. This revealed that a drug-like compound that inhibits cell death-regulatory proteins called IAPs could promote death of the infected cells.

"When we treated our infection models with this compound, we were able to significantly reduce the amount of tuberculosis disease," he said.

"The longer the treatment was used, the greater the reduction of disease."

The research team was able to replicate these results using various different IAP inhibitors.

"Excitingly, many of these compounds are already in clinical trials for other types of diseases and have proven to be safe and well-tolerated by patients," Dr Stutz said.

"We predict that if these compounds were progressed for treating tuberculosis, they would be most effective if used alongside existing antibiotic treatments."

Opening the door to new treatment methods

Professor Marc Pellegrini said until now, antibiotics were the only treatment for tuberculosis, which were limited in their application due to increasing antibiotic resistance.

"Unlike antibiotics, which directly kill bacteria, IAP inhibitors kill the cells that the tuberculosis bacteria need to survive," he said.

"The beauty of using a host-directed therapy is that it doesn't directly target the microbe, it targets a host process. By targeting the host rather than the microbe, the chances of resistance developing are incredibly low."

The team hope the research will lead to better treatments for tuberculosis.

"This research increases our understanding of the types of immune responses that are beneficial to us, and this is an important step towards new treatments for tuberculosis, very few of which have been developed in the last 40 years," Dr Stutz said.

"We have demonstrated that host-directed therapies are viable for infections such as tuberculosis, which is particularly important in the era of extensive antibiotic resistance."

INFORMATION:

This work was made possible with funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council, the Sylvia and Charles Viertel Charitable Foundation, The Harry Secomb Trust and the Victorian Government.

Ants are omnipresent, and we often get blisters after an ant bite. But do you know the molecular mechanism behind it? A research team led by Professor Billy K C CHOW from the Research Division for Molecular and Cell Biology, Faculty of Science, the University of Hong Kong (HKU), in collaboration with Dr Jerome LEPRINCE from The Institut national de la santé et de la recherche médicale (INSERM) and Professor Michel TREILHOU from the Institut National Universitaire Champollion in France, have identified and demonstrated a novel small peptide isolated from the ant venom can initiate an immune pathway via a pseudo-allergic receptor MRGPRX2. The study ...

Rather than waiting for certainty in sea-level rise projections, policymakers can plan now for future coastal flooding by addressing existing inequities among the most vulnerable communities in flood zones, according to Stanford research.

Using a methodology that incorporates socioeconomic data on neighborhood groups of about 1,500 people, scientists found that several coastal communities in San Mateo County, California - including half the households in East Palo Alto - are at risk of financial instability from existing social factors or anticipated flooding through 2060. Even with coverage from flood insurance, these residents would not be able to pay for damages from flooding, which could lead to homelessness or bankruptcy ...

Led by Professor Robert Read and Dr Jay Laver from the NIHR Southampton Biomedical Research Centre and the University of Southampton, the work is the first of its kind.

Together they inserted a gene into a harmless type of a bacteria, that allows it to remain in the nose and trigger an immune response. They then introduced these bacteria into the noses of healthy volunteers via nose drops.

The results, published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, showed a strong immune response against bacteria that cause meningitis. Published in ...

Through a complex, self-reinforcing feedback mechanism, colorectal cancer cells make room for their own expansion by driving surrounding healthy intestinal cells to death - while simultaneously fueling their own growth. This feedback loop is driven by an activator of the innate immune system. Researchers from the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) and the University of Heidelberg discovered this mechanism in the intestinal tissue of fruit flies.

Maintaining the well-functioning state of an organ or tissue requires a balance of cell growth and differentiation on the one hand, and the elimination of defective cells on the other. The intestinal epithelium is a well-studied example of this balance, termed "tissue homeostasis": Stem cells ...

North Carolina State University researchers found that a four-week training course made a substantial difference in helping special education teachers anticipate different ways students with learning disabilities might solve math problems. The findings suggest that the training would help instructors more quickly identify and respond to a student's needs.

Published in the Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, researchers say their findings could help teachers in special education develop strategies to respond to kids' math reasoning and questions in advance. They also say the findings point to the importance of mathematics education preparation for special education teachers - an area where researchers ...

COLUMBUS, Ohio -- As typical social and academic interaction screeched to a halt last year, many young people began experiencing declines in mental health, a problem that appeared to be worse for those whose connections to family and friends weren't as tight, a new study has found.

In June 2020, researchers invited participants in an ongoing study of teenage boys and young men in urban and Appalachian Ohio to complete a survey examining changes to mood, anxiety, closeness to family and friends, and other ways the pandemic affected their lives. The study, co-led by researchers at The Ohio State University and Kenyon College, appears in the Journal of Adolescent Health.

Nearly a third of the 571 participants reported that their mood ...

Chemotherapy is widely used to treat cancer patients. During the treatment, chemotherapeutic agents affect various biochemical processes to kill or reduce the growth of cancer cells, which divide uncontrollably in patients. However, the cell-damaging effect of chemotherapy affects cancer cells but also in principle many other cell types, including cycling blood cells. This puts the hematopoietic system under severe stress and pushes hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the bone marrow to produce fresh cells and replenish the stable pool of differentiated blood cells in the body.

Researchers from the MPI of Immunobiology and Epigenetics, together with colleagues from the University of Freiburg, Lyon, Oxford, and St Jude Children's Research Hospital in Memphis, now discovered ...

MORGANTOWN, W.Va. - Some LGBTQ+ people want to be part of faith communities. And though they have concerns about inclusion, they hope to find a faith community that feels like a home, based on West Virginia University research.

Megan Gandy, BSW program director at the WVU School of Social Work, is a lesbian and former fundamentalist evangelical Christian whose personal experiences told a story that differed from research available in 2015 when she conceptualized her study.

Gandy said the existing research either focused on the positive impacts of faith communities (which excluded LGBTQ+ people) ...

LAWRENCE -- Substance use disorder has long been considered a key factor in cases of parental neglect. But new research from the University of Kansas shows that such substance abuse does not happen in a vacuum. When examining whether parents investigated by Child Protective Services engaged in neglectful behaviors over the past year, a picture emerges that suggests case workers should look at substance misuse within the context of other factors, like mental health and social supports, to better prevent child neglect and help families.

KU researchers analyzed data of parents investigated ...

Proteomics produces enormous amounts of data, which can be very complex to analyze and interpret. The free software platform MaxQuant has proven to be invaluable for data analysis of shotgun proteomics over the past decade. Now, Jürgen Cox, group leader at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry, and his team present the new version 2.0. It provides an improved computational workflow for data-independent acquisition (DIA) proteomics, called MaxDIA. MaxDIA includes library-based and library-free DIA proteomics and permits highly sensitive and accurate data analysis. Uniting data-dependent and data-independent acquisition into one world, MaxQuant 2.0 is a big step towards improving applications ...