Investigators at the Stanford University School of Medicine and the Buck Institute for Research on Aging have built an inflammatory-aging clock that's more accurate than the number of candles on your birthday cake in predicting how strong your immune system is, how soon you'll become frail or whether you have unseen cardiovascular problems that could become clinical headaches a few years down the road.

In the process, the scientists fingered a bloodborne substance whose abundance may accelerate cardiovascular aging.

The story of the clock's creation will be published July 12 in Nature Aging.

"Every year, the calendar tells us we're a year older," said David Furman, PhD, the study's senior author. "But not all humans age biologically at the same rate. You see this in the clinic -- some older people are extremely disease-prone, while others are the picture of health."

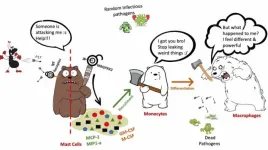

This divergence, Furman said, traces in large part to differing rates at which people's immune systems decline. The immune system -- a carefully coordinated collection of cells, substances and strategies with which evolution has equipped us to deal with threats such as injuries or invasions by microbial pathogens -- excels at mounting a quick, intense, localized, short-term, resist-and-repair response called acute inflammation. This "good inflammation" typically does its job, then wanes within days. (An example is that red, swollen finger you see when you have a splinter, and the rapid healing that follows.)

As we grow older, a low-grade, constant, bodywide "bad inflammation" begins to kick in. This systemic and chronic inflammation causes organ damage and promotes vulnerability to a who's who of diseases spanning virtually every organ system in the body and including cancer, heart attacks, strokes, neurodegeneration and autoimmunity.

To date, there have been no metrics for accurately assessing individuals' inflammatory status in a way that could predict these clinical problems and point to ways of addressing them or staving them off, Furman said. But now, he said, the study has produced a single-number quantitative measure that appears to do just that.

Furman directs the Stanford 1000 Immunomes Project and is a visiting scholar at Stanford's Institute for Immunity, Transplantation and Infection. In addition, he's an associate professor at the Novato, California-based Buck Institute for Research on Aging and director of the Artificial Intelligence Platform at the same institute.

Lead authors of the study are Nazish Sayed, MD, PhD, assistant professor of vascular surgery at Stanford, and Yingxiang Huang, PhD, senior data scientist at the Buck Institute.

1,001 blood samples

For the 1000 Immunomes Project, blood samples were drawn from 1,001 healthy people ages 8-96 between 2009 and 2016. The samples were subjected to a barrage of analytical procedures determining levels of immune-signaling proteins called cytokines, the activation status of numerous immune-cell types in responses to various stimuli, and the overall activity levels of thousands of genes in each of those cells.

The new study employed artificial intelligence to boil all this data down to a composite the researchers refer to as an inflammatory clock. The strongest predictors of inflammatory age, they found, were a set of about 50 immune-signaling proteins called cytokines. Levels of those, massaged by a complex algorithm, were sufficient to generate a single-number inflammatory score that tracked well with a person's immunological response and the likelihood of incurring any of a variety of aging-related diseases.

In 2017, the scientists assessed nearly 30 1000 Immunomes Project participants ages 65 or older whose blood had been drawn in 2010. They measured the participants' speed at getting up from a chair and walking a fixed distance and, through a questionnaire, their ability to live independently ("Can you walk by yourself?" "Do you need help getting dressed?"). Inflammatory age proved superior to chronological age in predicting frailty seven years later.

Next, Furman and his colleagues obtained blood samples from an ongoing study of exceptionally long-lived people in Bologna, Italy, and compared the inflammatory ages of 29 such people (all but one a centenarian) with those of 18 50- to 79-year-olds. The older people had inflammatory ages averaging 40 years less than their calendar age. One, a 105-year-old man, had an inflammatory age of 25, Furman said.

To further assess inflammatory age's effect on mortality, Furman's team turned to the Framingham Study, which has been tracking health outcomes in thousands of individuals since 1948. The Framingham study lacked sufficient data on bloodborne-protein levels, but the genes whose activity levels largely dictate the production of the inflammatory clock's cytokines are well known. The researchers measured those cytokine-encoding genes' activity levels in Framingham subjects' cells. This proxy for cytokine levels significantly correlated with all-cause mortality among the Framingham participants.

A key substance

The scientists observed that blood levels of one substance, CXCL9, contributed more powerfully than any other clock component to the inflammatory-age score. They found that levels of CXCL9, a cytokine secreted by certain immune cells to attract other immune cells to a site of an infection, begin to rise precipitously after age 60, on average.

Among a new cohort of 97 25- to 90-year-old individuals selected from the 1000 Immunomes Project for their apparently excellent health, with no signs of any disease, the investigators looked for subtle signs of cardiovascular deterioration. Using a sensitive test of arterial stiffness, which conveys heightened risk for strokes, heart attacks and kidney failure, they tied high inflammatory-age scores -- and high CXCL9 levels -- to unexpected arterial stiffness and another portent of untoward cardiac consequences: excessive thickness of the wall of the heart's main pumping station, the left ventricle.

CXCL9 has been implicated in cardiovascular disease. A series of experiments in laboratory dishware showed that CXCL9 is secreted not only by immune cells but by endothelial cells -- the main components of blood-vessel walls. The researchers showed that advanced age both correlates with a significant increase in endothelial cells' CXCL9 levels and diminishes endothelial cells' ability to form microvascular networks, to dilate and to contract.

But in laboratory experiments conducted on tissue from mice and on human cells, reducing CXCL9 levels restored youthful endothelial-cell function, suggesting that CXCL9 directly contributes to those cells' dysfunction and that inhibiting it could prove effective in reducing susceptible individuals' risk of cardiovascular disease.

"Our inflammatory aging clock's ability to detect subclinical accelerated cardiovascular aging hints at its potential clinical impact," Furman said. "All disorders are treated best when they're treated early."

INFORMATION:

Other Stanford study co-authors are Robert Tibshirani, PhD, professor of biomedical data science and of statistics; Trevor Hastie, PhD, professor of statistics and of biomedical data; senior research scientist Lu Cui, PhD; Human Immune Monitoring Center Immunoassays director Yael Rosenberg-Hasson, PhD; former neurology instructor Benoit Lehalier, PhD; former postdoctoral scholar Shai Shen-Orr, PhD; Holden Maecker, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology; Cornelia Dekker, MD, professor of pediatric infectious diseases, emeritus; Tony Wyss-Coray, PhD, professor of neurology and neurological sciences; Francois Haddad, MD, clinical professor of cardiovascular medicine; Jose Montoya, MD, former professor of infectious diseases; Joseph Wu, MD, professor of radiology and director of the Stanford Cardiovascular Institute; and Mark Davis, PhD, professor of microbiology and immunology and director of the Institute for Immunity, Transplantation and Infection.

Researchers from the Buck Institute, Edifice Health, the University of North Carolina, Technion-Israel Institute of Technology, the University of Leuven, the University of Bologna, the University of Florence and the Institute of Neurological Sciences of Bologna also contributed to the work.

The work was funded by the Stanford Alzheimer's Disease Research Center, the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, the Ellison Foundation, the National Institutes of Health (grants U19 AI057229, U19 AI090019, UL1 RR025744, K01 HL135455 and P50 AG047366) and the Paul F. Glenn Foundation.

The Stanford University School of Medicine consistently ranks among the nation's top medical schools, integrating research, medical education, patient care and community service. For more news about the school, please visit http://med.stanford.edu/school.html. The medical school is part of Stanford Medicine, which includes Stanford Health Care and Stanford Children's Health. For information about all three, please visit http://med.stanford.edu.