Simulating microswimmers in nematic fluids

A combination of two simulation techniques has allowed researchers to investigate how swimming microparticles propel themselves through 'nematic liquid crystals' -- revealing some unusual behaviors

2021-07-13

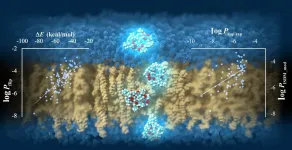

(Press-News.org) Artificial microswimmers have received much attention in recent years. By mimicking microbes which convert their surrounding energy into swimming motions, these particles could soon be exploited for many important applications. Yet before this can happen, researchers must develop methods to better control the trajectories of individual microswimmers in complex environments. In a new study published inEPJ E, Shubhadeep Mandal at the Indian Institute of Technology Guwahati (India), and Marco Mazza at the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organisation in Göttingen (Germany) and Loughborough University (UK), show how this control could be achieved using exotic materials named 'nematic liquid crystals' (LCs) - whose viscosity and elasticity can vary depending on the direction of an applied force.

The duo's discoveries could inform the future use of cargo-carrying microswimmers in delicate medical procedures: including drug delivery, disease monitoring, and non-invasive surgery. Through the use of biocompatible nematic LCs, these techniques could be easily and safely integrated with the bodies of patients. Typically, microswimmers propel themselves forward by either pushing or pulling the fluid surrounding them. So far, these motions haven't been widely studied in less conventional fluids like nematic LCs - which have orderly crystal structures, but can also flow like liquids.

Mandal and Mazza studied this scenario using 'multiparticle collision dynamics' algorithms, which describe how the atomic structures of nematic LCs vary over time. Combined with simulations of spherical microswimmers, the algorithms allowed them to investigate how the direction-dependent viscosities and elasticities of nematic LCs can affect the speeds and orientations of spherical microswimmers. Previous studies showed that their motions are starkly different to those found in conventional fluids; with microswimmers following non-random trajectories to minimise their elastic energy. Mandal and Mazza now also show that a microswimmer's speed will vary depending on whether it pushes or pulls the surrounding fluid; and also becomes slower when it pushes with a stronger force. The duo now hope that their simulation techniques could be easily extended to model the dynamics of multiple microswimmers.

INFORMATION:

Reference

S Mandal, M G Mazza (2021) Multiparticle collision dynamics simulations of a squirmer in a nematic fluid, Eur. Phys. J. E 44:64. DOI https://doi.org/10.1140/epje/s10189-021-00072-3

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-07-13

A new model tracking the vertical movement of algae-covered microplastic particles offers hope in the fight against plastic waste in our oceans.

Research led by Newcastle University's Dr Hannah Kreczak is the first to identify the processes that underpin the trajectories of microplastics below the ocean surface. Publishing their findings in the journal Limnology and Oceanography the authors analysed how biofouling - the accumulation of algae on the surface of microplastics, impacts the vertical movement of buoyant particles.

The researchers found that particle properties ...

2021-07-13

Informing people about how well the new COVID-19 vaccines work could boost uptake among doubters substantially, according to new research.

The study, led by the University of Bristol and published in the British Journal of Health Psychology, shows the importance of raising awareness of vaccine efficacy, especially if it compares very favourably to another well-established vaccine.

The research focused on adults who were unsure about being vaccinated against COVID-19. Those who were given information about the vaccine's efficacy scored 20 per cent higher on a measure ...

2021-07-13

Scientists at Tokyo Institute of Technology have developed a computational method based on large-scale molecular dynamics simulations to predict the cell-membrane permeability of cyclic peptides using a supercomputer. Their protocol has exhibited promising accuracy and may become a useful tool for the design and discovery of cyclic peptide drugs, which could help us reach new therapeutic targets inside cells beyond the capabilities of conventional small-molecule drugs or antibody-based drugs.

Cyclic peptide drugs have attracted the attention of major pharmaceutical companies around the world as promising alternatives to ...

2021-07-13

Rescuing a member of their own social group, but not a stranger, triggers motivational and social reward centres in rats' brains, suggests a report published today in eLife.

The study provides the first description of similar brain activity in both rats and humans underlying this socially biased behaviour. The findings add to our understanding of social biases and could help with developing ways to promote cooperation outside of an individual's social group.

"Humans, as well as many other creatures, are biased toward helping other members of their social groups ...

2021-07-13

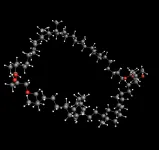

Crenarchaeol is a large, closed-loop lipid that is present in the membranes of ammonium-oxidizing archaea, a unicellular life form that exists ubiquitously in the oceans. In comparison to other archaeal membrane lipids, crenarchaeol is very complex and, so far, attempts to confirm its structure by synthesizing the entire molecule have been unsuccessful. Organic chemists from the University of Groningen have taken up this challenge and discovered that the proposed structure for the molecule was largely, but not entirely, correct.

Crenarchaeol contains 86 carbon atoms and is a 'macrocycle, a large closed loop. No fewer than 22 positions in the molecule are chiral. The molecule can be present in two forms that are each other's mirror image, like a left and a right hand. In the crenarchaeol ...

2021-07-13

A new University of Iowa study suggests that metabolism of plant-based dietary substances by specific gut bacteria, which are lacking in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS), may provide protection against the disease.

The study led by Ashutosh Mangalam, PhD, UI associate professor of pathology, shows that a diet rich in isoflavone, a phytoestrogen or plant-based compound that resembles estrogen, protects against multiple sclerosis-like symptoms in a mouse model of the disease. Importantly, the isoflavone diet was only protective when the mice had gut microbes capable of breaking ...

2021-07-13

MORGANTOWN, W.Va.--Just as helicopter traffic reporters use their "bird's eye view" to route drivers around roadblocks safely, radiation oncologists treating a variety of cancers can use new guidelines developed by a West Virginia University researcher to reduce mistakes in data transfer and more safely treat their patients.

Ramon Alfredo Siochi--the director of medical physics at WVU--led a task group to help ensure the accuracy of data that dictates a cancer patient's radiation therapy. The measures he and his colleagues recommended in their new report safeguard against medical errors in a treatment that more than half of all cancer patients receive.

"The most common mistake that happens in radiation oncology is the transfer of information from one system to another," Siochi, ...

2021-07-13

How we sense texture has long been a mystery. It is known that nerves attached to the fingertip skin are responsible for sensing different surfaces, but how they do it is not well understood. Rodents perform texture sensing through their whiskers. Like human fingertips, whiskers perform multiple tasks, sensing proximity and shape of objects, as well as surface textures.

Mathematicians from the University of Bristol's Department of Engineering Mathematics, worked with neuroscientists from the University of Tuebingen in Germany, to understand how the motion of a whisker across a surface translates texture information into neural signals that can be perceived by the brain.

By carrying out high ...

2021-07-13

Scientists have found new evidence of menopause in killer whales - raising fascinating questions about how and why it evolved.

Most animals breed throughout their lives. Only humans and four whale species are known to experience menopause, and scientists have long been puzzled about why this occurs.

Killer whales are a diverse species made up of multiple separate ecotypes (different types within a species) across the world's oceans that differ in their prey specialisation and patterns of social behaviour.

Previous studies have found menopause in an ecotype called "resident" killer whales whose social structure appears to favour "grandmothering" (females using their energy and knowledge ...

2021-07-13

When a doctor gives a patient antibiotics for a bacterial infection, they usually require them to finish the entire treatment, even when symptoms go away. This is to ensure the drugs kill off any remaining bacteria. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Visiting Scientist Raffaella Sordella investigated a similar problem that occurs in some lung cancers.

Approximately 15% of non-small cell lung cancers have a mutation in a growth receptor called EGFR, causing tumor cells to grow uncontrollably. Researchers developed an effective drug that inhibits EGFR and ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Simulating microswimmers in nematic fluids

A combination of two simulation techniques has allowed researchers to investigate how swimming microparticles propel themselves through 'nematic liquid crystals' -- revealing some unusual behaviors