(Press-News.org) Although the risk of a child being admitted to hospital due to COVID-19 is small, a new UK study has found that around 1 in 20 of children hospitalised with COVID-19 develop brain or nerve complications linked to the viral infection.

The research, published in The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health and led by the University of Liverpool, identifies a wide spectrum of neurological complications in children and suggests they may be more common than in adults admitted with COVID-19.

While neurological problems have been reported in children with the newly described post-COVID condition paediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS), the capacity of COVID-19 to cause a broad range of nervous system complications in children has been under-recognised.

To address this, the CoroNerve Studies Group, a collaboration between the universities of Liverpool, Newcastle, Southampton and UCL, developed a real-time UK-wide notification system in partnership with the British Paediatric Neurology Association.

Between April 2020 and January 2021, they identified 52 cases of children less than 18 years old with neurological complications among 1,334 children hospitalised with COVID-19, giving an estimated prevalence of 3.8%. This compares to an estimated prevalence of 0.9% in adults admitted with COVID-19.

Eight (15%) children presenting with neurological features did not have COVID-19 symptoms although the virus was detected by PCR, underscoring the importance of screening children with acute neurological disorders for the virus.

Ethnicity was found to be a risk factor, over two thirds of children being of Black or Asian background.

For the first time, the study identified key differences between those with PIMS-TS versus those with non-PIMS-TS neurological complications. The 25 children (48%) diagnosed with PIMS-TS displayed multiple neurological features including encephalopathy, stroke, behavioural change, and hallucinations; they were more likely to require intensive care. Conversely, the non-PIMS-TS 27 (52%) children had a primary neurological disorder such as prolonged seizures, encephalitis (brain inflammation), Guillain-Barré syndrome and psychosis. In almost half of these cases, this was a recognised post-infectious neuro-immune disorder, compared to just one child in the PIMS-TS group, suggesting that different immune mechanisms are at work.

Short-term outcomes were apparently good in two thirds (65%) although a third (33%) had some degree of disability and one child died at the time of follow-up. However, the impacts on the developing brain and longer-term consequences are not yet known.

First author Dr Stephen Ray, a Wellcome Trust clinical fellow and paediatrician at the University of Liverpool said: "The risk of a child being admitted to hospital due to COVID-19 is small, but among those hospitalised, brain and nerve complications occur in almost 4%. Our nationwide study confirms that children with the novel post-infection hyper-inflammatory syndrome PIMS-TS can have brain and nerve problems; but we have also identified a wide spectrum of neurological disorders in children due to COVID-19 who didn't have PIMS-TS. These were often due to the child's immune response after COVID-19 infection."

Joint senior-author Dr Rachel Kneen, a Consultant Paediatric Neurologist at Alder Hey Children's NHS Foundation Trust and honorary clinical Senior Lecturer at the University of Liverpool said: "Many of the children identified were very unwell. Whilst they had a low risk of death, half needed intensive care support and a third had neurological disability identified. Many were given complex medication and treatments, often aimed at controlling their own immune system. We need to follow these children up to understand the impact in the long term."

Joint senior-author Dr Benedict Michael, a senior clinician scientist and MRC Fellow at the University of Liverpool said: "Now we appreciate the capacity for COVID-19 to cause a wide range of brain complications in those children who are hospitalised with this disease, with the potential to cause life-long disability, we desperately need research to understand the immune mechanisms which drive this. Most importantly- How do we identify those children at risk and how should we treat them to prevent lasting brain injury? We are so pleased that the UK government has funded our COVID-CNS study to understand exactly these questions so that we can help inform doctors to better recognise and treat these children."

INFORMATION:

Neurological manifestations of Covid-19 infection in UK hospitalised children and adolescents: a prospective national cohort study, The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health, can be found here: http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanchi/article/PIIS2352-4642(21)00193-0/fulltext

A scientific review has found evidence that a disruption in blood clotting and the first line immune system could be contributing factors in the development of psychosis.

The article, a joint collaborative effort by researchers at RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences, Cardiff University and the UCD Conway Institute, is published in Molecular Psychiatry.

Recent studies have identified blood proteins involved in the innate immune system and blood clotting networks as key players implicated in psychosis.

The researchers analysed these studies and developed a new theory that proposes the imbalance of both of these systems leads to inflammation, which in turn contributes to the development of psychosis.

The work proposes that alterations ...

Tokyo, Japan - Primary immunodeficiencies, such as severe combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID), occur when the immune system does not work properly, leading to increased susceptibility to various infections, autoimmunity, and cancers. Most of these are inherited and have an underlying genetic causes. A team at TMDU has identified a novel disorder resulting from a mutation in a protein called AIOLOS, which functions through a previously unknown pathogenic mechanism called heterodimeric interference.

The gene family known as IKAROS zinc finger proteins (IKZFs) is associated with the development of lymphocyte, a type of white blood cell involved ...

URBANA, Ill. - U.S. corn and soybean varieties have become increasingly heat and drought resistant as agricultural production adapts to a changing climate. But the focus on developing crops for extreme conditions has negatively affected performance under normal weather patterns, a University of Illinois study shows.

"Since the 1950s, advances in breeding and management practices have made corn and soybean more resilient to extreme heat and drought. However, there is a cost for it. Crop productivity with respect to the normal temperature and precipitation is getting lower," says Chengzheng Yu, doctoral student in the Department ...

New research led by the University of Cambridge suggests that autism can be detected at 18-30 months using the Quantitative Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (Q-CHAT), but it is not possible to identify every child at a young age who will later be diagnosed as autistic. The results are published today in The BMJ Paediatrics Open.

The team at the Autism Research Centre in Cambridge conducted a prospective population screening study of nearly 4,000 toddlers using a parent-report instrument they developed, called the Quantitative Checklist for Autism in Toddlers (Q-CHAT). Toddlers were screened at 18 months and followed up at 4 years.

The ...

Northwestern University engineers have developed the first full, three-dimensional (3D), dynamic simulation of a rat's complete whisker system, offering rare, realistic insight into how rats obtain tactile information.

Called WHISKiT, the new model incorporates 60 individual whiskers, which are each anatomically, spatially and geometrically correct. The technology could help researchers predict how whiskers activate different sensory cells to influence which signals are sent to the brain as well as provide new insights into the mysterious nature of human touch.

The research was published last week in the Proceedings ...

Bat conversations might be light on substance, according to researchers from the University of Cincinnati.

Echoes from bats are so simple that a sound file of their calls can be compressed 90% without losing much information, according to a study published in the journal PLOS Computational Biology.

The study demonstrates how bats have evolved to rely on redundancy in their navigational "language" to help them stay oriented in their complex three-dimensional world.

"If you can make decisions with little information, everything becomes simpler. That's nice because you don't need a lot of complex neural machinery to process and store that information," study co-author Dieter Vanderelst ...

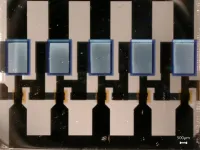

Physicists of the Technische Universität Dresden introduce the first implementation of a complementary vertical organic transistor technology, which is able to operate at low voltage, with adjustable inverter properties, and a fall and rise time demonstrated in inverter and ring-oscillator circuits of less than 10 nanoseconds, respectively. With this new technology they are just a stone's throw away from the commercialization of efficient, flexible and printable electronics of the future. Their groundbreaking findings are published in the renowned journal "Nature Electronics".

Poor performance is still impeding the commercialization ...

Researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) and the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, have taken a big step toward developing targeted treatments and vaccines against a family of viruses that attacks the gastrointestinal tract.

Each year in the United States circulating strains of the human norovirus are responsible for approximately 20 million cases of acute gastroenteritis. Hallmark symptoms include severe abdominal cramping, diarrhea and vomiting.

Several vaccine candidates are in clinical trials, but it is unclear how effective they will be, given the periodic emergence of novel norovirus variants. Developing ...

All cancers fall into just two categories, according to new research from scientists at Sinai Health, in findings that could provide a new strategy for treating the most aggressive and untreatable forms of the disease.

In new research out this month in Cancer Cell, scientists at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute (LTRI), part of Sinai Health, divide all cancers into two groups, based on the presence or absence of a protein called the Yes-associated protein, or YAP.

Rod Bremner, senior scientist at the LTRI, said they have determined that all cancers ...

WHAT:

A new study published in Nature Communications suggests that gene therapy delivered into the brain may be safe and effective in treating aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency. AADC deficiency is a rare neurological disorder that develops in infancy and leads to near absent levels of certain brain chemicals, serotonin and dopamine, that are critical for movement, behavior, and sleep. Children with the disorder have severe developmental, mood dysfunction including irritability, and motor disabilities including problems with talking ...