The genetic manipulation spurred the animals' heart muscle cells -- called cardiomyocytes -- to proliferate and grow larger by an amount comparable to normal mice that swam for up to three hours a day, the authors write in the journal Cell.

This specific gene manipulation can't be done in humans, they say, but the findings may suggest a future strategy for repairing injured hearts through muscle regeneration.

"If we learned to manipulate this pathway with specific exercise regimens or with drugs, we might be able to achieve some of the benefits produced by exercise-related heart enlargement," said Bruce Spiegelman, PhD, of Dana-Farber, the study's co-senior author with Anthony Rosenzweig, MD, of BIDMC. Pontus Bostrom, PhD, MD, a postdoctoral fellow at Dana-Farber, is the first author.

The investigators found that the mildly enlarged hearts of the genetically altered mice proved to be surprisingly resistant to a model of cardiac stress that mimics valvular heart disease or the effects of high blood pressure. Someday this observation might lead to therapeutic measures to treat or prevent heart failure, Spiegelman said.

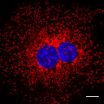

Only recently have scientists discovered that adult cardiomyocytes retain the potential to begin dividing and spawning new muscle cells. In their new publication, the authors describe for the first time a genetic trigger that responds to physical exercise and turns on a molecular pathway that jump-starts cardiomyocyte growth.

"It's well documented that exercise has beneficial effects on metabolism and skeletal muscle, but we hypothesized that it might also have more direct beneficial effects in the heart itself that could be exploited to protect against heart failure," noted Rosenzweig, a cardiologist at BIDMC.

While most previous studies have investigated diseased hearts, these investigators focused their studies on the changes that occur in hearts after endurance exercise. Heart muscle enlargement, or hypertrophy, in response to exercise is popularly known as "athlete's heart" in humans. This process of benign heart muscle growth, the scientists found, involves a distinctly different series of molecular events from those causing pathological hypertrophy -- the enlarged and damaged heart seen in patients suffering from factors like high blood pressure.

While the molecular networks involved in pathological hypertrophy have been studied extensively, there's been little research on the pathways leading to benign heart enlargement, despite the fact that "exercise protects the heart at so many levels," said Bostroom. "We decided to try and find a gene that could be driving some of the important changes we see in exercise."

First, they had adult mice swim daily for increasing amounts of time, and after 14 days found that their hearts were mildly enlarged as a result. Other mice with restricted blood flow in their aorta also showed enlargement, but of the type associated with heart disease. The researchers then screened both sets of animals against a collection of all known transcription factors -- proteins that turn gene activity up or down -- and compared their expression in the two types of heart enlargement.

The key differences turned out to be in a pair of transcription factors acting in concert. One, C/EPB-beta, had reduced activity in the exercised mice while the other, CITED4, was more active.

So, could turning down C/EPB-beta in normal mice cause their hearts to grow as if they had been working out -- even though they did no extra exercise? The answer was yes: Genetic manipulation to reduce C/EPB-beta expression raised the activity of CITED4, and in those mice, cardiomyocytes began dividing and growing in size until their heart muscles resembled those of the endurance swimmers. The mice also had markedly improved maximal exercise capacity even without exercise training.

Importantly, lowering C/EPB-beta expression also protected mice from developing heart failure as a result of restricted aortic blood flow. It is likely that the more-robust cardiomyocytes played an important role in the resistance to heart failure, said the investigators, but they couldn't rule out that other actions of reduced C/EPB-beta and increased CITED4 also contributed.

The authors concluded that developing greater insight into the pathways affecting C/EPB-beta protein expression, or drugs that suppress C/EPB-beta expression in the heart, could be of significant clinical value. "By understanding the pathways that benefit the heart with exercise, we may be able to exploit those for patients who aren't able to exercise," said Rosenzweig. "If there were a way to modulate the same pathway in a beneficial way, it would open up new avenues for treatment."

### Other authors are from Dana-Farber, BIDMC, and Brigham and Women's Hospital.

Support for the research was provided in part by the Leducq Foundation Network of Research Excellence and the National Institutes of Health.

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center is a patient care, teaching and research affiliate of Harvard Medical School, and consistently ranks in the top four in National Institutes of Health funding among independent hospitals nationwide. BIDMC is clinically affiliated with the Joslin Diabetes Center and is a research partner of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center. BIDMC is the official hospital of the Boston Red Sox. For more information, visit www.bidmc.harvard.edu.

Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (www.dana-farber.org) is a principal teaching affiliate of the Harvard Medical School and is among the leading cancer research and care centers in the United States. It is a founding member of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (DF/HCC), designated a comprehensive cancer center by the National Cancer Institute. It provides adult cancer care with Brigham and Women's Hospital as Dana-Farber/Brigham and Women's Cancer Center and it provides pediatric care with Children's Hospital Boston as Dana-Farber/Children's Hospital Cancer Center. Dana-Farber is the top ranked cancer center in New England, according to U.S. News & World Report, and one of the largest recipients among independent hospitals of National Cancer Institute and National Institutes of Health grant funding.

END