(Press-News.org) ITHACA, N.Y. - A new method that analyzes how individual immune cells react to the bacteria that cause tuberculosis could pave the way for new vaccine strategies against this deadly disease, and provide insights into fighting other infectious diseases around the world.

The cutting-edge technologies were developed in the lab of Dr. David Russell, the William Kaplan Professor of Infection Biology in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology in the College of Veterinary Medicine, and detailed in new research published in the Journal of Experimental Medicine on July 22.

For years, Russell's lab has sought to unravel how Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the bacteria that cause tuberculosis, infect and persist in their host cells, which are typically immune cells called macrophages.

The lab's latest innovation combines two analytical tools that each target a different side of the pathogen-host relationship: "reporter" Mtb bacteria that glow different colors depending on how stressed they are in their environment; and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), which yields RNA transcripts of individual host macrophage cells.

"For the first time ever, Dr. Davide Pisu in my lab combined these two approaches to analyze Mtb-infected immune cells from an in vivo infection," Russell said.

After infecting mice with the fluorescent reporter Mtb bacteria, Russell's team was able to gather and flow-sort individual Mtb-infected macrophages from the mouse lung. The researchers then determined which macrophages promoted Mtb growth (sporting happy, red-glowing bacteria) or contained stressed Mtb unlikely to grow (unhappy, green-glowing bacteria).

Next, they took the two sorted, infected macrophage populations and ran them through single-cell RNA sequencing analysis, thereby generating transcriptional profiles of each individual host cell in both populations.

When the scientists compared the macrophage single cell sequencing data with the reporter bacteria phenotype, they found an almost perfect one-to-one correlation between the fitness status of the bacterium and the transcriptional profile in the host cell. Macrophages that housed unhappy green bacteria also expressed genes that were known to discourage bacterial growth, while those with happy red bacteria expressed genes known to promote bacterial growth.

Scientific experiments rarely play out so nicely.

"What absolutely stunned us is how well it worked," Russell said. "When Davide Pisu showed me the analysis I nearly fell off my chair."

Normally, phenotypes and transcriptional profiles are two characteristics that seldom come together in a perfect match, and this almost never happens from in vivo data.

This near-perfect matchup revealed new nuances.

"While our previous results identifying the resident alveolar macrophages (AM) as permissive and the blood monocyte-derived recruited macrophages (IM) as controlling Mtb infection was correct in a broad sense, we found, unsurprisingly, that this was an oversimplification," Russell said.

There was variation even within these two different macrophage types: Some AM cells controlled Mtb growth while some IMs were allowing bacterial expansion. The team found that comparable subsets of immune cells were present in both human and mouse lung samples.

An additional step in the study was to look at whether the responses of AM and IM cells to Mtb were epigenetically controlled--meaning that the cells' traits are due to certain genes being turned off or on by molecular switches This could explain how two sets of macrophages respond differently. Using a read-out of a cell's epigenetic landscape, they found that this was the case.

"The analysis showed that when these cells are exposed to Mtb or the vaccine strain- through infection or vaccination, respectively - their epigenetic programming has a major influence over whether their response leads to disease control or progression," Russell said.

Armed with this body of new information, the Russell lab plans to hit the ground running to identify novel therapeutics. "We're going to begin by screening libraries of known epigenetic inhibitor compounds to see which ones might be useful in modifying the immune response," Russell said.

If they do find promising compounds - ones that push macrophages towards an anti-Mtb behavior - they could potentially be used in combination with vaccines to assist a patient's immune system in protecting against tuberculosis.

The finding lays a foundation for more powerful studies on how pathogens affect individual cells, allowing for a holistic examination of the system.

"This is a roadmap that lets us look across an entire population of cells and see how a single perturbation impacts the cells across that population," Russell said. "We can test for drug efficacy in in vivo infection without any preconceived limitation on how compounds may function."

This approach is extremely flexible and could be used in the study of any intracellular pathogen, including viruses, and is readily applicable to any animal challenge model.

INFORMATION:

A new study, led by University of Minnesota Twin Cities engineering researchers, shows that the stiffness of protein fibers in tissues, like collagen, are a key component in controlling the movement of cells. The groundbreaking discovery provides the first proof of a theory from the early 1980s and could have a major impact on fields that study cell movement from regenerative medicine to cancer research.

The research is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS), a peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary, high-impact scientific journal.

Directed cell movement, or what scientists call "cell contact guidance," refers to a phenomenon when the orientation of cells ...

Researchers at the University of São Paulo (USP) in Brazil investigated the effects of regular exercise on the physical and mental health of 344 volunteers during the pandemic. The study compared the effectiveness of three techniques: sessions led in person by a fitness instructor, sessions featuring an online instructor but no supervision, and sessions supervised remotely by an instructor via video call.

The two kinds of session with professional supervision had the strongest effects on physical and mental health. According to the researchers, this was due to the possibility of increasing ...

New Brunswick, NJ--Even at term, gestational age may have an impact on children's academic performance, findings of a new study suggest. The research showed an association between gestational age at term and above-average rankings in a number of academic subjects.

The study, published in Pediatrics, compared teacher-reported outcomes for 1,405 9-year-old children in the United States, analyzing performance in mathematics, science and social studies, and language and literacy, for those born at 37 through 41 weeks gestation. It found that longer gestational age was significantly associated with average or above-average rankings in all areas. It also suggested a general pattern of worse outcomes for children born at early term (37-38 weeks) and better outcomes for those born at late ...

Plastics offer many benefits to society and are widely used in our daily life: they are lightweight, cheap and adaptable. However, the production, processing and disposal of plastics are simply not sustainable, and pose a major global threat to the environment and human health. Eco-friendly processing of reusable and recyclable plastics derived from plant-based raw materials would be an ideal solution. So far, the technological challenges have proved too great. However, researchers at the University of Göttingen have now found a sustainable method - "hydrosetting", which uses water at normal conditions - to process and reshape a new type of hydroplastic polymer called cellulose cinnamate (CCi). The research was published ...

HOUSTON -- (July 22, 2021) -- Researchers who want bacteria to feel right at home in the laboratory have put out a new welcome mat.

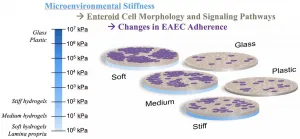

Rice University bioengineers and Baylor College of Medicine scientists looking for a better way to mimic intestinal infections that cause diarrhea and other diseases have built and tested a set of hydrogel-based platforms to see if they could make both transplanted cells and bacteria comfy.

As a mechanical model of intestinal environments, the lab's soft, medium and hard polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogels were far more welcoming to the cells that normally line the gut than the glass and plastic usually used by laboratories. These cells can then host bacteria like Escherichia coli that are sometimes pathogenic. The ability to study their ...

Many people find it morally impermissible to put kidneys, children, or doctorates on the free market. But what makes a market transaction morally repugnant in the eyes of the public? And which transactions trigger the strongest collective disapproval? Researchers from the Max Planck Institute for Human Development and the Robert Koch Institute have addressed these questions. Their findings, published in Cognition, offer new entry points for policy interventions.

Would you be willing to sell a kidney or be paid to spend time on a date? If not, then ...

Nuclear fusion offers the potential for a safe, clean and abundant energy source.

This process, which also occurs in the sun, involves plasmas, fluids composed of charged particles, being heated to extremely high temperatures so that the atoms fuse together, releasing abundant energy.

One challenge to performing this reaction on Earth is the dynamic nature of plasmas, which must be controlled to reach the required temperatures that allow fusion to happen. Now researchers at the University of Washington have developed a method that harnesses advances in the computer gaming industry: It uses a gaming graphics card, or GPU, to run the control system for their prototype fusion reactor.

The team published ...

As any juror will tell you, piecing together a crime from a series of documents tendered in a courtroom is no easy feat, especially when a person's future hangs in the balance.

Delivering the correct verdict on car accident and murder cases is contingent on good spatial awareness, but short of being at the scene of the crime, the room for error is large.

However, thanks to the advent of virtual reality (VR), jurors now have a better chance of making the right decision.

A new study published by the University of South Australia provides overwhelming evidence ...

The discovery of a Roman road submerged in the Venice Lagoon is reported in Scientific Reports this week. The findings suggest that extensive settlements may have been present in the Venice Lagoon centuries before the founding of Venice began in the fifth century.

During the Roman era, large areas of the Venice Lagoon which are now submerged were accessible by land. Roman artefacts have been found in lagoon islands and waterways, but the extent of human occupation of the lagoon during Roman times has been unclear.

Mapping the lagoon floor using sonar, Fantina Madricardo and colleagues discovered 12 archaeological structures aligned in a northeasterly direction for 1,140 metres, in an area of the lagoon ...

Newly-hatched pterosaurs may have been able to fly but their flying abilities may have been different from adult pterosaurs, according to a study published in Scientific Reports.

Pterosaurs were a group of flying reptiles that lived during the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Periods (228 to 66 million years ago). Due to the rarity of fossilised pterosaur eggs and embryos, and difficulties distinguishing between hatchlings and small adults, it has been unclear whether newly-hatched pterosaurs were able to fly.

Darren Naish and colleagues modelled hatchling flying abilities using previously obtained wing measurements from four established hatchling and embryo fossils from two pterosaur species, ...