(Press-News.org) New research from the University of Otago debunks a long-held belief about our ancestors' eating habits.

For more than 60 years, researchers have believed Paranthropus, a close fossil relative of ours which lived about one to three million years ago, evolved massive back teeth to consume hard food items such as seeds and nuts, while our own direct ancestors, the genus Homo, is thought to have evolved smaller teeth due to eating softer food such as cooked food and meats.

However, after travelling to several large institutes and museums in South Africa, Japan and the United Kingdom and studying tooth fractures in more than 20,000 teeth of fossil and living primate species, Dr Ian Towle, an Otago biological anthropologist, working with Dr Carolina Loch, of the Faculty of Dentistry, says this "neat picture is far more complex than once thought".

"By individually studying each tooth and recording the position and size of any tooth fractures, we show tooth chipping does not support regular hard food eating in Paranthropus robustus, therefore potentially putting an end to the argument that this group as a whole were hard food eaters," he says.

Dr Towle says the findings challenge our understanding of dietary and behavioural changes during human evolution.

"The results are surprising, with human fossils so far studied - those in our own genus Homo - showing extremely high rates of tooth fractures, similar to living hard object eating primates, yet Paranthropus show extremely low levels of fracture, similar to primates that eat soft fruits or leaves.

"Although in recent years there has been a slow acceptance that another species of Paranthropus, Paranthropus boisei, found in East Africa, was unlikely to have regularly eaten hard foods, the notion that Paranthropus evolved their large dental apparatus to eat hard foods has persisted. Therefore, this research can be seen as the final nail in the coffin of Paranthropus as hard object feeders."

The fact that humans show such contrasting chipping patterns is equally significant and will have "knock on" effects for further research, particularly research on dietary changes during human evolution, and why the human dentition has evolved the way it has, he says.

"The regular tooth fractures in fossil humans may be caused by non-food items, such as grit or stone tools. However, regardless of the cause, these groups were subjected to substantial tooth wear and fractures. So, it raises questions to why our teeth reduced in size, especially compared to groups like Paranthropus."

Dr Towle's research will now focus on if our dentition evolved smaller due to other factors to allow other parts of the skull to expand, leading to evolution then favouring other tooth properties to protect it against wear and fracture, instead of increased tooth size.

"This is something we are investigating now, to see if tooth enamel may have evolved different characteristics among the great apes. Our research as a whole may also have implications for our understanding of oral health, since fossil human samples typically show immaculate dental health.

"Since extreme tooth wear and fractures were the norm, our ancestors likely evolved dental characteristics to not just cope with but actually utilise this dental tissue loss. For example, without substantial tooth wear our dentitions can face all sorts of issues, including impacted wisdom teeth, tooth crowding and even increased susceptibility to cavities."

INFORMATION:

Paranthropus robustus tooth chipping patterns do not support regular hard food mastication, co-authored by Dr Towle and Dr Loch, was published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

Tooth chipping prevalence and pattern in extant primates, co-authored by Dr Towle and Dr Loch was published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology.

Chipping and wear patterns in extant primate and fossil hominin molars: 'Functional' cusps are associated with extensive wear but low levels of fracture, co-authored by Dr Towle and Dr Loch was published in the Journal of Human Evolution.

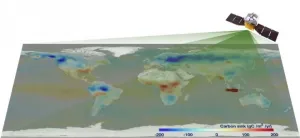

About six gigatons -- roughly 12 times the mass of all living humans -- of carbon appears to be emitted over land every year, according to data from the Chinese Global Carbon Dioxide Monitoring Scientific Experimental Satellite (TanSat).

Using data on how carbon mixes with dry air collected from May 2017 to April 2018, researchers developed the first global carbon flux dataset and map. They published their results in Advances in Atmospheric Sciences.

The map was developed by applying TanSat's satellite observations to models of how greenhouse gasses are exchanged among Earth's atmosphere, land, ...

Reston, VA--A new radiotracer that detects iron in cancer cells has proven effective, opening the door for the advancement of iron-targeted therapies for cancer patients. The radiotracer, 18F-TRX, can be used to measure iron concentration in tumors, which can help predict whether a not the cancer will respond to treatment. This research was published in the July issue of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

All cancer cells have an insatiable appetite for iron, which provides them the energy they need to multiply. As a result, tumors have higher levels of iron than normal tissues. Recent advances in chemistry have led scientists to take advantage of this altered state, targeting the expanded cytosolic ...

MUSC Hollings Cancer Center was one of 28 clinical sites around the world that participated in the LOTIS-2 trial to test the efficacy of Loncastuximab tesirine, a promising new treatment for aggressive B-cell lymphoma. The results of the single-arm, phase 2 trial were published online in May 2021 in Lancet Oncology.

Brian Hess, M.D., a Hollings researcher and lymphoma specialist at MUSC Health, was instrumental in bringing the phase 2 trial to Hollings. The manufacturer of Loncastuximab tesirine, ADC Therapeutics S.A., sponsored the trial.

B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a blood cancer that begins in the lymph nodes, spleen or bone marrow. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common subtype of aggressive NHL. New treatment options are vital for patients with DLBCL. ...

Due to the global efforts to meet sustainability standards, many countries are currently looking to replace concrete with wood in buildings. France, for example, will require that all new public buildings will be made from at least 50 percent wood or other sustainable materials starting in 2022.

Because wood is prone to degradation when exposed to sunlight and moisture, protective coatings can help bring wood into wider use. Researchers at Aalto University have used lignin, a natural polymer abundant in wood and other plant sources, to create a safe, low-cost and high-performing coating for use in construction.

'Our new coating has great potential to ...

A new optogenetic tool, a protein that can be controlled by light, has been characterized by researchers at Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB). They used an opsin - a protein that occurs in the brain and eyes - from zebrafish and introduced it into the brain of mice. Unlike other optogenetic tools, this opsin is not switched on but rather switched off by light. Experiments also showed that the tool could be suitable for investigating changes in the brain that are responsible for the development of epilepsy.

The teams led by Professor Melanie Mark from the Behavioural Neurobiology Research Group and Professor Stefan Herlitze from the Department ...

As the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 continues to evolve, immunologists and infectious diseases experts are eager to know whether new variants are resistant to the human antibodies that recognized initial versions of the virus. Vaccines against COVID-19, which were developed based on the chemistry and genetic code of this initial virus, may confer less protection if the antibodies they help people produce do not fend off new viral strains. Now, researchers from Brigham and Women's Hospital and collaborators have created an "atlas" that charts how 152 different antibodies attack a major ...

Many species within Kenya's Tana River Basin will be unable to survive if global temperatures continue to rise as they are on track to do - according to new research from the University of East Anglia.

A new study published in the journal PLOS ONE today outlines how remaining within the goals of the Paris Agreement would save many species.

The research also identifies places that could be restored to better protect biodiversity and contribute towards global ecosystem restoration targets.

Researcher Rhosanna Jenkins carried out the study as part of her PhD at UEA's School of Environmental Sciences.

She said: "This research shows how many species within Kenya's Tana River Basin will be unable to survive if global temperatures continue to rise as they are on track to do.

"But remaining ...

For young soccer players, participating in repetitive technical training activities involving heading during practice may result in more total head impacts but playing in scrimmages or actual soccer games may result in greater magnitude head impacts. That's according to a small, preliminary study released today that will be presented at the American Academy of Neurology's Sports Concussion Conference, July 30-31, 2021.

"Headers are a fundamental component to the sport of soccer. Therefore, it is important to understand differences in header frequency and magnitude across practice and game settings," said study author Jillian Urban, PhD, MPH, of Wake ...

University of Virginia School of Medicine researchers have discovered a previously unknown repair process in the brain that they hope could be harnessed and enhanced to treat seizure-related brain injuries.

Common seizure-preventing drugs do not work for approximately a third of epilepsy patients, so new and better treatments for such brain injuries are much needed. UVA's discovery identifies a potential avenue, one inspired by the brain's natural immune response.

Using high-powered imaging, the researchers were able to see, for the first time, that immune cells called microglia were not just removing damaged material after experimental seizures but actually appeared to be healing damaged neurons.

"There has been mounting generic support for the idea that microglia ...

WESTMINSTER, Colorado - July 23, 2021 - Horseweed is a serious threat to both agricultural crops and natural landscapes around the globe. In the U.S., the weed is prolific and able to emerge at any time of the year.

Fall emerging horseweed overwinters as a rosette, while spring emerging horseweed skips the rosette stage and grows upright. In some instances, both rosette and upright plants emerge simultaneously in mid-summer. These unpredictable growth patterns create challenges for growers as they try to develop an appropriate weed management plan.

In a study featured in the journal Weed Science, a team from Michigan State University explored whether environmental cues could be used to predict horseweed growth ...